Equitable Investment and Local Arts Agencies

Research Findings, Proposed Goals for Change, and Recommended Strategies

“Every system is perfectly designed to get the result it gets.”

— W. Edwards Deming (possibly apocryphal)

Cultural equity is critical to the arts and culture sector’s long-term viability, as well as to the ability of the arts to contribute to healthy, vibrant, equitable communities for all. At the core of the challenges related to cultural equity are the historically inequitable distribution of resources and the value systems, biases, and systemic barriers associated with that distribution.

Each year the United States’ 4,500 local arts agencies1 (LAAs) collectively invest2 an estimated $2.8 billion in their local arts and culture ecosystems. This includes an estimated $600 million in direct investment in artists and arts and culture organizations through grants, contracts, and loans. For comparison, all of private philanthropy directly invests approximately $4 billion3 annually to the arts, corporations about $1.5 billion,4 state arts agencies about $300 million,5 and the National Endowment for the Arts about $100 million.6

This makes LAAs, collectively, the largest distributor of publicly-derived funds to arts and culture, and one of the largest and steadiest underwriters of artists and creative workers in the United States. It is therefore crucial that LAAs employ a strong lens of equity7 to consider the full scope of their investments, including not only direct financial infusions such as grants, contracts, and loans, but the estimated $2.2 billion each year that’s expended on staff salaries, vendors, direct-to-community programming, overhead, marketing and communications, and more.

In January 2019, with the support of the Ford Foundation, Americans for the Arts compiled and released two paired reports: “Equitable Investment Policies and Practices in the Local Arts Field,” which analyzed LAAs and their investment practices, and “Strategies to Achieve Equitable Investment by Local Arts Agencies and Nexus Organizations,” which compiled recommendations from a national advisory group of funders, artists, local arts leaders, and researchers. Together, these reports shed light on both how LAAs and nexus organizations are (and are not) incorporating an equity lens into their investments and how the field — ranging from national service organizations to agencies on the ground — can take targeted steps to transform systems and address the inequities that exist in financial distribution.

Research Findings

“Equitable Investment Policies and Practices in the Local Arts Field” reviews results from the 2018 Local Arts Agency Profile, with a particular focus on an added module that analyzed how, when, and where LAAs in the United States consider equity in the deployment of their funds, time, space, and staff. The data was gathered from a broadly representative sample of 537 LAAs in the United States of varying budget size, community size, tax status, geography, etc.

Overall, the report tells a story of a field where direct and indirect practices centered on equity are on the rise. While major demographic challenges continue to exist among staff at LAAs of all sizes, the majority of large LAAs — and, in most cases, mid-size LAAs as well — are taking a variety of steps to consider, engage, and develop support mechanisms for the full diversity of their communities. LAAs with more limited financial capacity and smaller staff sizes are not able to participate in these new mechanisms at the same rate, but are inclined to want to know how they can.

That said, there is still significant work to do. Only half of LAAs with DEI-related policies say that those policies affect fiscal decisions. The majority of entry- and mid-level staff do not have access to supported professional development. And, perhaps most starkly, LAA funds are distributed inequitably, with 73% of award dollars going to just 16% of grant recipients. While this lopsided distribution is comparatively more equitable than that of private philanthropy, in which 60% of arts funding goes to the top 2% of organizations,8 it should still function as an alarm bell, given the aggregate dollars at stake and the public (and publicly-funded) nature of the majority of LAAs in the country.

The centering of equity in the investment practices of the LAA field is necessary to the continued relevance of not only LAAs themselves, but the arts and culture sectors each LAA nurtures. This is a jumping-off point.

Staff and Board Commission Knowledge, Readiness, and Demographics

- LAA staffs and boards/commissions are more homogeneous than the general US population, and have fewer people from historically marginalized populations in their ranks. This is particularly true among the three staff positions most likely to impact investment strategy: CEOs, COOs, and Grants Managers. Board and commission members are, in aggregate, whiter, older, wealthier, and more likely to be politically liberal than the general US population.

- Nearly nine out of ten respondents indicated their staff, board, and volunteers currently had the appropriate level of skill to respond to the needs of their constituents, and almost half of respondents indicated these groups currently had the appropriate level of diversity.

- Overall access to professional development increases with budget size. In most organizations, senior leaders can access, and are supported in, professional development, while middle management and entry-level staff have only infrequent access to similar opportunities, particularly in small and mid-size LAAs.

- About a third of LAAs administer equity-related training for board, staff, or volunteers. One out of ten organizations require staff or grantees to participate in such workshops, while two in ten LAAs provide or underwrite training or educational materials for staff related to communicating with non-arts sectors.

Research, Evaluation, Tracking, and Assessment

- The percentage of organizations that track any sort of demographic data increases with budget size. Almost half of LAAs in the smallest category do no such tracking, while over three-quarters of the largest do. Among those that do track demographic trends, the most prevalent study groups are the general community population, arts audiences, individual artists, and board members or staff of other arts groups.

- Budget and staff size also impacts whether evaluation occurs. Almost a quarter of LAAs with budgets under $100,000 do not collect any information for the purposes of impact evaluation, while all LAAs with annual budgets of $1 million or more do. Among LAAs who do evaluate impact, the most prevalent methods are tracking attendance or ticket sales of programs, conducting interviews or surveys of audience/community members and/or civic leaders, conducting interviews or surveys of organizations or individuals they support, and collecting written narratives and/or financial reports from grantees.

Policies, Guidelines, and Internal Practices

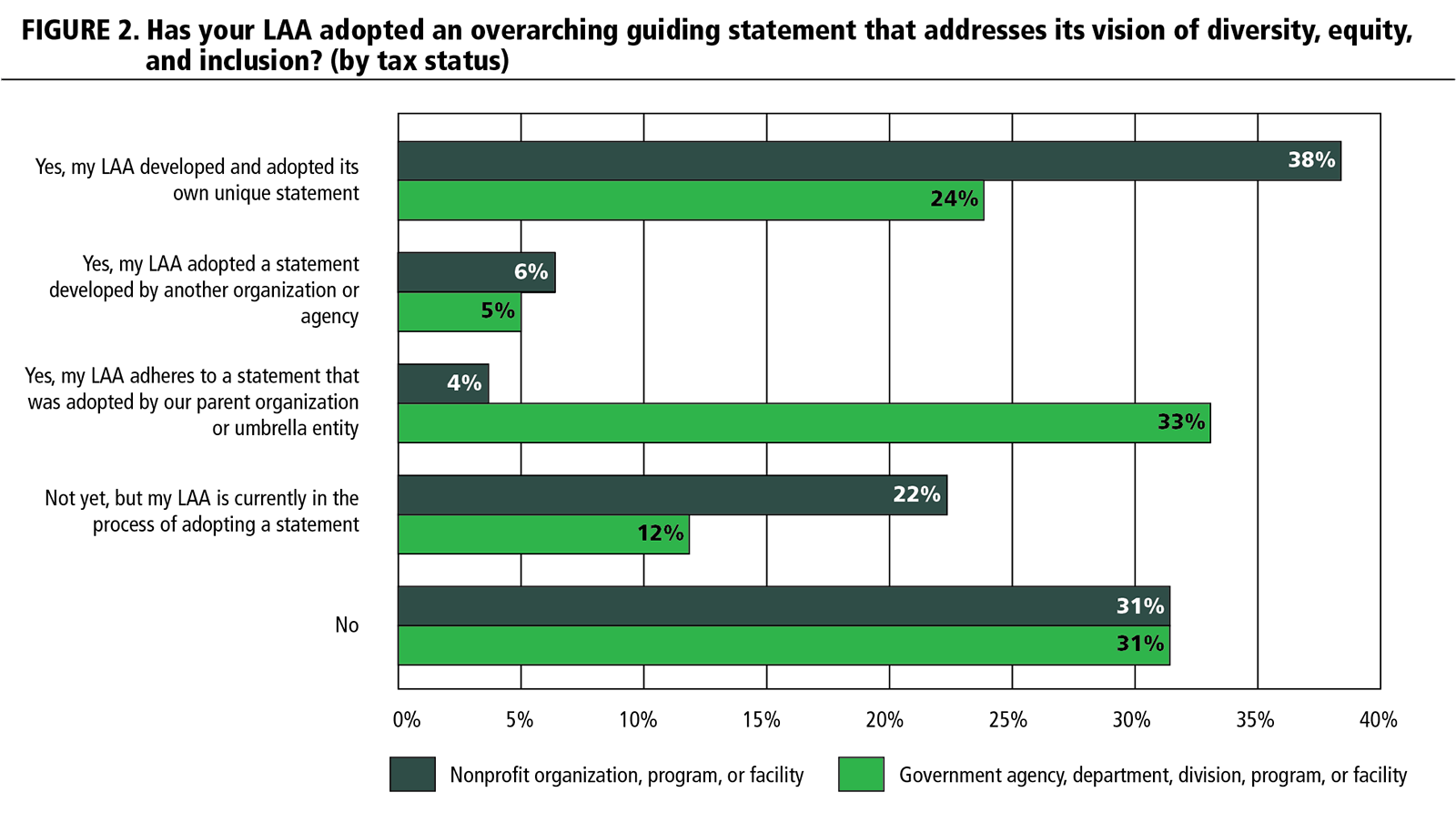

- Half of LAAs currently adhere to a diversity, equity, and inclusion policy of some sort — an increase of 21% since a similar survey in 2015 — and one in five are currently working on creating or adopting a diversity, equity, and inclusion statement. LAAs with larger budgets are more likely to have such a statement, as are LAAs that indicate that diversity, equity, and inclusion is one of their top five priority areas.

- Tax status has a marked effect on the nature of diversity, equity, and inclusion statements. Private LAAs (those that operate outside city or county government) are more likely to have developed their own statement, while public LAAs (those within city or county government) are much more likely to have adopted a statement from an umbrella entity (such as a city or county).

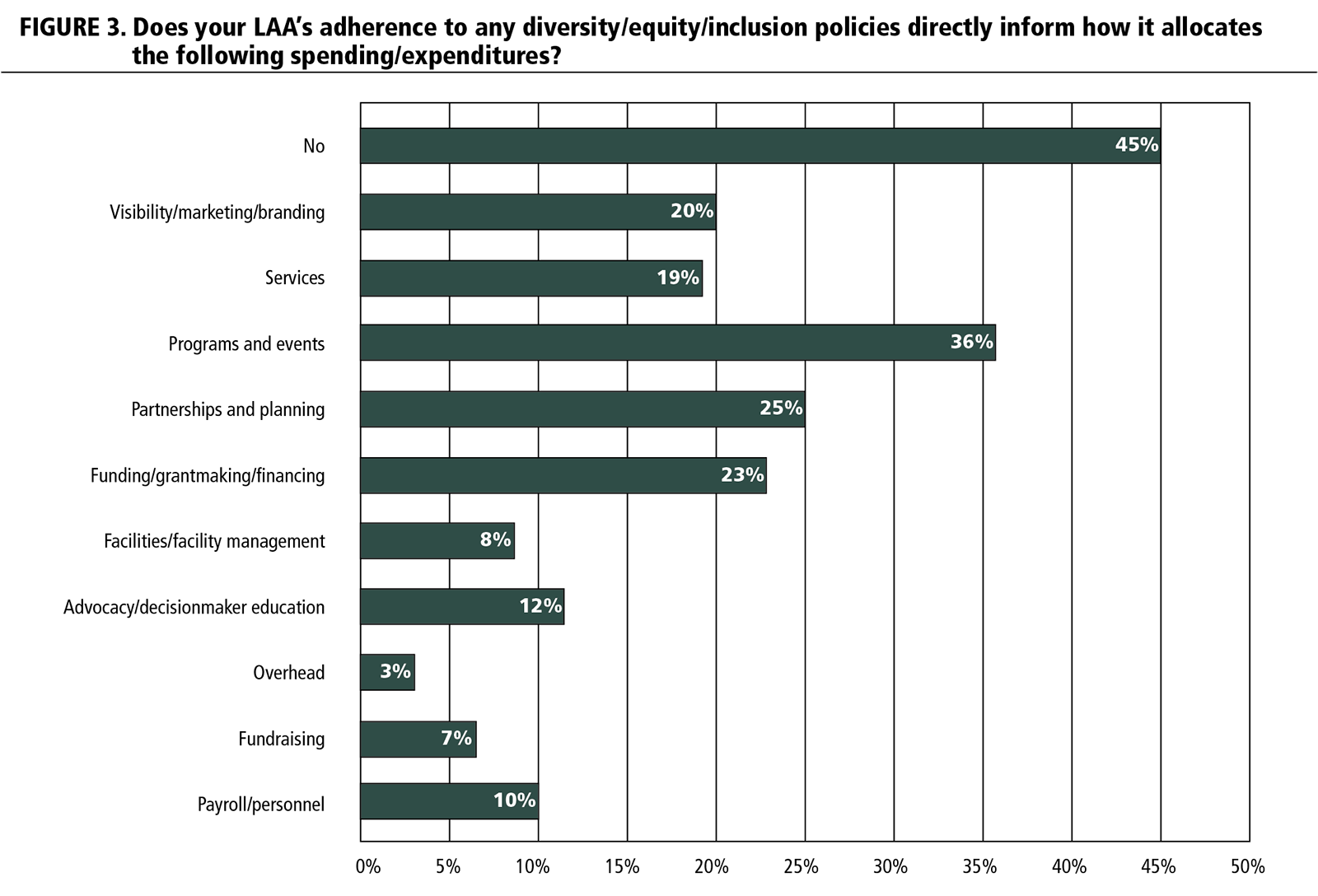

- LAAs rely equally on written and unwritten/informal policies related to diversity, equity, and inclusion, depending on the policy area. Written policies were most prevalent in terms of staffing/hiring, boards/commissions, grantmaking, and contractors/interns. About half of the LAAs who indicate they had diversity, equity, and inclusion policies of some sort also indicate that those policies inform a component of fiscal decision making. This is true for both public and private agencies.

- Eight in ten LAAs have taken some sort of action related to diversity, equity, and inclusion since May of 2016. As in other areas, smaller organizations were much more likely to indicate they had taken no action since May of 2016.

Financial Distribution and Investment (Including Grantmaking)

- We extrapolate that, collectively, LAAs have approximately $2.8 billion in annual expenditures across the whole field. This number is derived from the respondents of this survey, who reported $777 million in revenue and $873 million in expense in 2018. Of the expenses, approximately 25% were for direct financial distribution activities like grants, contracts, and loans.

- In terms of revenue for LAAs, 40% of revenue comes from public dollars, 27% from contributed income, and 25% from products and services. The remainder is in-kind or miscellaneous. The public or private nature of the LAA has significant impact on the make-up of revenue, with public LAAs receiving more than twice as much funding from public coffers as private LAAs. Regardless of tax status, the percentage of public dollars (particularly local public dollars) increases dramatically as the LAA gets larger.

- In terms of expenditures, on average, LAAs expend about half their budget on externally-focused work like grants/contracts and cultural programs and services, and half their budget on internally-focused work like payroll/personnel, administrative overhead, and fundraising. Mid-size LAAs expend a significantly higher percentage on payroll and personnel, and a significantly smaller percentage on grants and contracts.

- The LAAs in the study distributed $380 million to artists and arts organizations in the form of grants, contracts, loans, start-up capital, and commissions in Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This represents 79% of the total amount requested. Just over ten thousand requests for funding were fully or partially honored by respondents in 2018.

- 73% of the total dollars awarded by LAAs in the study went to the top 16% of organizations by budget size. 6% of the total dollars awarded went to the bottom 45% of organizations by budget size. Grants requests from organizations are significantly more likely than requests from individual artists to receive at least partial funding.

- Around half of all LAA respondents provide financial support either directly or indirectly to organizations other than arts and culture nonprofits, including non-501(c)(3)’s and/or non-arts organizations.

- The presence of funding programs specifically intended to serve underserved groups is tied to budget size, with such programs being much more prevalent inside larger LAAs. 85% of LAAs with such programs do some sort of special communications outreach. 82% of LAAs with such programs conduct some extra level of administration or co-design with the intended community.

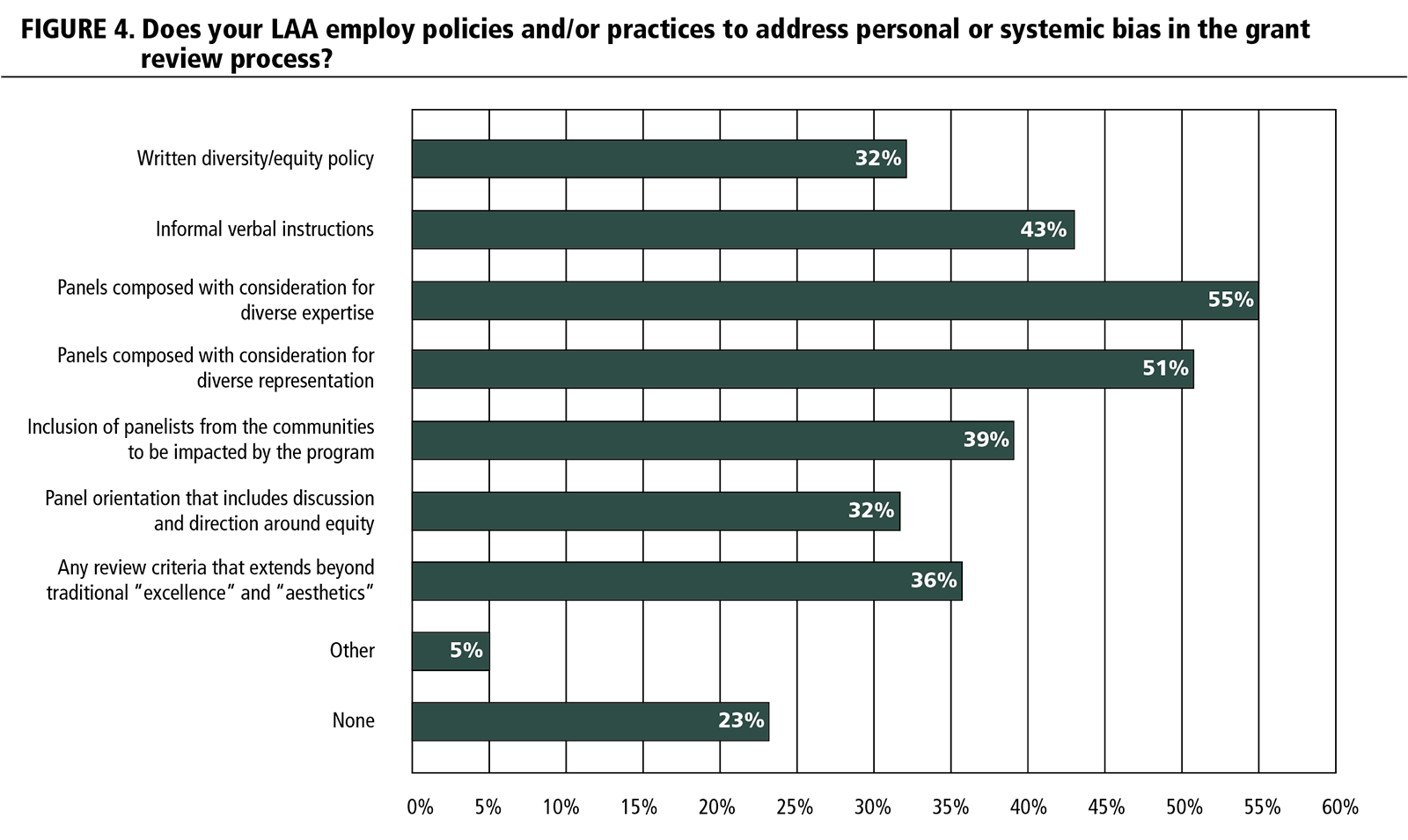

- About three quarters of LAAs with granting programs integrate mechanisms for managing personal or systemic bias in the grant review process. The most prevalent practices are: composing panels with consideration of diverse expertise and/or representation, and delivering informal and/or written diversity, equity, and inclusion policies or instructions to adjudicators.

- About a third of respondents indicated that they had incorporated review criteria that extends beyond historical, Eurocentric “excellence” and “aesthetics,” and a similar number incorporate discussion and direction around the consideration of equity in the panel orientation process.

Non-Monetary Community Investment, Programs, and Services

Recommendations to Center Equity

Concurrently with, and then in reaction to, the research conducted on equitable investment practice within LAAs, Americans for the Arts convened a field-based advisory group to develop a set of goals and strategies to encourage field transformation, comprehensive education, increased cultural consciousness, and the centering of equity.

Service and funding organizations, such as Americans for the Arts, that support LAAs and nexus organizations must encourage the thoughtful, quick, and decisive transition of inequitable investment policies and practices toward equity. In the short-term, this means propelling shifts now in the nature and structure of LAA investment programs, policies, and practices. In the long-term, it means supporting and driving root transformation in the systems and structures that undergird LAA investments in the community and cultural ecosystem, transforming the minds and hearts of those who currently control and impact such investment strategies, and training and establishing a more diverse and representative set of leaders among those who make decisions and set policies.

Since systems generally function as they were originally designed at their core, the core must be addressed for systemic change to occur. In the United States, beliefs and assumptions have been constructed to assign power and resources that benefit and value a dominant normative (white, male, heterosexual, wealthy, etc.) and disadvantage or actively harm the “other.” This ideological worldview permeates our history, economic strategies, and institutional systems, and it must be examined, altered, or dismantled for any progress to be made towards equity. Right now, the default system of investment for most LAAs — like most systems of investment in the United States — is not designed with equity as the objective. Without addressing the deep, core, upstream origins of inequity, strategies implemented for change may be of limited impact.

A constant dialogue of downstream, immediate steps and upstream, long-term systemic changes can, we believe, begin to both immediately address existing inequities and transform the system, so that we as a field can move from triaging a broken system to existing within one that is more just, equitable, and representative of the full potential of the arts in community life.

Current standard bearers and equity champions need opportunities for support, connection, and exchange with peers and experts. Being the only advocate, or one of just a few, for equity-based systemic change within an organization — often without the expertise, resources, or authority necessary to accomplish the shift needed — can be a substantial challenge. Personal and community expectations for change can weigh heavily. Concurrent feelings of urgency, responsibility, and isolation can lead to frustration, resentment, and/or burn-out.

Meanwhile, for most LAAs, a significant amount of positional and structural power is situated in their boards or commissions and with authorizing agencies and influential donors of dominant cultural organizations that LAAs serve, who are, on average, whiter, older, more liberal, and more able-bodied than the general US population. Until the people with the power to make decisions about investments look like the full breadth of the community impacted by those investments, the system will continue to be inequitable and subject to the conscious and unconscious biases of the individuals in power.

While the demographics of most communities are changing, the influence of the rising demographic groups doesn’t increase in proportion to their size. These groups don’t (and for some time won’t) have the same power, wealth, and clout as entrenched, mostly white and wealthy, individuals. Disrupting this imbalance requires, in the short-term, more communications frames to get more people to be part of the solution, and in the long-term, a different set of people with different demographics at the helm.

Messaging, data, and training are needed to raise awareness of positional power, privilege, and bias, both explicit and implicit, as well as how these factors affect the decision-making process and distribution policies and practices. Critical but tricky is how to communicate value and opportunity; realigning towards equity isn’t as much about a shift in “how it has always been,” but rather a vital course-correction that will benefit the entire community. While it is important to frame equity in ways that resonate with the value systems of those currently in power, when the rhetoric swings too heavily away from historical injustice and reconciliation there is a danger of undermining and re-traumatizing traumatized populations. Education of these individuals is a key component of the process and must be repeated as new members enter their positions. In addition, resistance or reticence on the part of long-term senior staff members can stymie organizational transformation or dishearten advocates for change within the organization.

Among many constantly competing priorities, it can be challenging to experiment and innovate — and can be even more challenging to do so in a way that allows for documentation, evaluation, and replication in other communities. By supporting better mechanisms for disseminating good practice, proliferating more detailed examples and how-to resources, and connecting communities, the national arts and culture community can help increase the number of evaluated, articulated models that are ready to adapt or adopt.

To transform core (upstream) LAA values and systems so that the whole system is working toward equitable objectives, LAA staff, as well as their boards and commissions, need the time and space to tackle the basic architecture and objectives of the system itself — including how culture is defined, and mechanisms such as cultural planning, asset mapping, and impact evaluation. These can themselves be fraught with implicit and/or unrecognized bias. Highlighting those biases, and providing alternative examples of practice, can begin to shift the underlying structures towards equity.

LAAs, and everyone else working in the arts and culture field, also need a set of local, state, and national networks to rely on. Currently, the various national service organizations have education, training, tools, and field change initiatives that are developed with a common purpose, but without significant coordination. Partnering around a subset of objectives related to equity could move the field farther and faster toward adoption of equitable policies and practices.

All parts of the cultural support system, from LAAs and nexus organizations to national service organizations, need to better understand the current state of grantmaking and investment, hiring, decision-making, etc. With more national and community-by-community comparable data on local investment strategies — investment types, how and when investments are made, where the funds and services are directed, who benefits, who is left out — and by developing skills in the field to understand and translate data into stories, we can develop informed analysis and strategies for making change.

In the end, these realities distill down to four core goals that the advisory group believes we must pursue collectively to move towards equity in investment.

- Goal 1: Support for Diverse Leadership (current and future)

Local standard bearers and champions in the movement for cultural equity, as well as a rising class of future arts leaders from the full demographic spectrum, are connected and supported to maintain motivation to drive change. In the long-term, the demographics of those in power must mirror those of the community. - Goal 2: Educated and Transformed Decision Makers

Decision makers with the power to direct cultural investment use an equity lens to implement or strengthen equitable policies, programs, and practices and support equity changemakers in their agencies and in the cultural ecosystem. In the long-term, all in power, including a broader group reflective of the full demographics of the community, are equipped to drive and support equity. - Goal 3: A Strong Body of Evidence-Based Equitable Investment Practices

Effective and innovative evidence-based equitable investment practices proliferate from community to community, supported by quality, accessible research, documentation, and evaluation, a national support network, and communities of shared learning/practice. - Goal 4: Sector-Wide Collective Action to Address Equity

Collaboration and communication among the national service organizations expands reach, improves the efficiency of field education for cultural equity, and accelerates adoption of equitable policies and practices.

In pursuit of these four goals, the advisory group proposed the following five strategies.

- Strategy 1: Communities of Practice and Shared Learning

Create new or promote existing communities of practice and peer convening opportunities for committed leaders to build bonds and trust; learn and grow through deep exchange; develop shared language; and reflect, iterate ideas, and develop strategies for moving work forward. - Strategy 2: Pipeline, Pre/Early- Professional Development, and Organizational Openness

Develop mechanisms for supporting, encouraging, and increasing opportunity for future arts leaders from the full demographic spectrum entering the field and progressing through early- and mid-career; ensure readiness and openness of the organizations into which they go; and lay the groundwork for a substantial long-term shift in the demographics of those making decisions, particularly about hiring, investment, and program development and delivery. - Strategy 3: Affordable and Available High-Quality Learning

Provide affordability and ease of access to high-quality training, toolkits, support materials, and more to LAA professionals at all career stages, and trustees and commissioners in the following critical areas: [1] anti-racism/anti-bias, power dynamics, and privilege; [2] authentic community engagement, empowerment, and input gathering; [3] how systems work, persist, are disrupted, and transform; [4] how to communicate about, and encourage participation in, equity initiatives; and [5] data competency, data-based storytelling, and evaluation. - Strategy 4: Research-Backed Tools for Doing the Work

Identify or develop tools to support self-assessment, benchmarking, and evaluation over time, including: [1] easy-to-use data gathering and analysis platforms for local assessment, data aggregation, and cross-community comparison; [2] a self-assessment rubric for LAAs to track progress and identify areas of improvement; [3] public opinion polling, national longitudinal data-gathering, and clearinghouses of germane field research and argumentation; and [4] effective equity messaging that compels engagement. - Strategy 5: Coordinate a National Support Network for Collective Impact

Establish a regular convening of point people within the national service organizations who are responsible for their equity-related work; develop a “field scan” to map existing equity-related efforts; and develop common goals that can be carried into independent and collaborative work.

Conclusion

Fair and equitable distribution of resources within the cultural sector of each community requires LAAs and other local funders to adhere to core practices and competencies that center equity and address bias, honor and embrace the inherent knowledge of the communities and constituents with which they engage, strengthen and broaden the leadership pipeline, support the fullest range of arts, cultural, and creative expression, and embrace new models of power-sharing and decision-making.

An essential component of achieving any of this prospective progress is an engaged philanthropic community that will support the difficult and expensive task of reworking or replacing inequitable systems. Without intervention, this system, like all systems, will continue to work as it was designed to do — yielding a future that is untenable and a sector that runs the risk of becoming irrelevant. While not necessarily sexy, such transformations, when achieved, will ripple out into the field, driving support for the full breadth and width of cultural life. It is up to us all.

Advisors

The advisory group members were:

Sandra Aponte, Chicago Community Trust

Charles Baldwin, Mass Cultural Council

Pam Breaux, National Association of State Arts Agencies

Jaime Dempsey, Arizona Commission on the Arts

Sally Dix, BRAVO Greater Des Moines

Patricia Efiom, City of Evanston

Toni Freeman, Arts and Science Council of Charlotte/Mecklenberg

Lane Harwell, Ford Foundation

Mari Horita, Artsfund

Rebecca Kinslow, Metropolitan Nashville Arts Commission

Takenya LaViscount, Arts and Humanities Council of Montgomery County

Abel Lopez, GALA Hispanic Theatre

Ruby Lopez Harper, Americans for the Arts

Clayton Lord, Americans for the Arts

Margaret Morton, Ford Foundation

Tariana Navas-Nieves, Denver Arts & Venues

Nichole Potzauf, Blue Ridge Mountains Arts Association

Angelique Power, Field Foundation

Margie Johnson Reese, Wichita Falls Arts and Culture Alliance

Axel Santana, PolicyLink

Barbara Schaffer Bacon, Americans for the Arts

Felicia Shaw, Regional Arts Commission of St. Louis

Jessica Stern, Americans for the Arts

Caroline Taiwo, Springboard for the Arts

Eddie Torres, Grantmakers in the Arts

Mara Walker, Americans for the Arts

Barbara Schaffer Bacon co-directs Animating Democracy, a program of Americans for the Arts that inspires, informs, promotes, and connects arts and culture as potent contributors to community, civic, and social change.

Ruby Lopez Harper is the director of Local Arts Services for Americans for the Arts, where she leads work to support Local Arts Agencies in grantmaking, community development, cultural equity, public art, and more.

Clayton Lord, Americans for the Arts’ vice president of Local Arts Advancement, works to ensure the arts are viewed as relevant and transformative in the lives of American citizens and communities.

Mara Walker is the chief operating officer for Americans for the Arts, responsible for the overall performance of the organization and the accomplishment of its strategic plan.

NOTES

- Local Arts Agencies (LAAs), of which there are 4,500 in the United States, promote, support, and develop the arts at the local level ensuring a vital presence for the arts throughout America’s communities. LAAs are diverse in their makeup — they have many different names and embrace a spectrum of artistic disciplines — but each works to sustain the health and vitality of the arts and artists locally and to make the arts accessible to all members of a community. Each LAA in America is unique to the community that it serves, and each evolves within its community.

- Investment is the allocation of a resource (money, time, space) in the expectation that it will yield a future benefit. “Equitable investment” is the centering of cultural equity in investment strategies, in particular the recognition and restructuring of inequitable systems of consideration, allocation, distribution, and evaluation in terms of such investments.

- Helicon Collaborative. Not Just Money. Helicon Collaborative. 2017. Web. http://heliconcollab.net/our_work/not-just-money/

- The Giving Institute. Giving USA 2018: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2017. The Giving Institute. 2018

- Ibid.

- National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. State Arts Agency Grantmaking and Funding Summary Report. National Assem- bly of State Arts Agencies. 2017. Web. https://nasaa-arts.org/nasaa_research/2016_grant_making_and_funding/

- National Endowment for the Arts. 2017 Annual Report. National Endowment for the Arts. 2018. Web. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/2017%20Annual%20Report.pdf

- Cultural equity embodies the values, policies, and practices that ensure that all people — including but not limited to those who have been historically, and continue to be, underrepresented based on race/ethnicity, age, disability, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, socioeconomic status, geography, citizenship status, or religion — are represented in the development of arts policy; the support of artists; the nurturing of accessible, thriving venues for expression; and the fair distribution of programmatic, financial, and informational resources. While intersectionality is real and crucial to providing entry for people at various stages of readiness, we acknowledge that racial inequity is central to most societal issues, particularly when it comes to the distribution of resources.

- Helicon Collaborative. Not Just Money. Helicon Collaborative. 2017. Web. http://heliconcollab.net/our_work/not-just-money/