The Knowledge-Centric Arts Organization

A Critical Role for Grantmakers

— John Naisbitt, Megatrends: 10 New Directions Transforming Our Lives (1982)

The nonprofit arts and cultural sector is at a critical inflection point. A combination of societal, economic, and operational trends has placed many organizations in a precarious position where their sustainability and relevance are challenged. Add to this a seemingly continuous increase in the growth and scope of data, information, technology, and systems that abound, and it is clear that a significant shift from the current state is needed. How can arts organizations become a part of today’s fast-paced knowledge society? What are the practices that will help them? More important, what is the critical new role that grantmakers must play in supporting and developing sustainable and relevant organizations, and what new strategies will ensure success?

Addressing these issues requires a rethinking of how arts organizations must operate in a knowledge-driven society, combined with a fundamental shift in the strategies used by grantmakers to support the sector. It is only when both grantee and grantor approaches align with the current realities that effective and lasting change can occur.

Based on exploratory interviews with the leadership of nonprofit arts organizations combined with an assessment of grantmaking practices of public and private grantmakers, this article seeks to understand the historical context and issues that have led to the current challenges and provides both organizational strategies and suggestions for grantmakers. The concept of a knowledge-centric arts organization is explored as an overall means toward building sustainability of the sector.1 The research finds three critical approaches for arts organizations and seven suggested approaches for grantmakers that, when combined, can help to ensure the long-term viability of the sector.

Toward a Knowledge Society: How Did We Get Here?

To understand how the arts and cultural sector has arrived at this critical juncture, it’s important to look back at the past two centuries of American history to understand the role of disruptive change. In that time frame, American society evolved from an industrial society to an information society to our current knowledge society. In the early American industrial society, economic growth was driven by the technologies of mass production and transportation. As the industrial society evolved into an information society, growth was driven by information technology, which sped up the commercialization of new ideas, created new forms of communication, and built new industries based on these technologies. Now, we have recently emerged into the knowledge society, where growth is driven by organizations and people that are able to create and use knowledge to advance their goals. Each of these transitions required wholesale changes in individual skills and institutional practices to ensure sustainability and relevancy in a rapidly changing environment. As a result, many arts organizations are facing challenges in becoming a part of the knowledge society. Most traditional nonprofit arts organizations came into existence during a period of relative stability and growth in the second half of the twentieth century, and as such many organizations find themselves challenged by a new environment brought on by the knowledge society.

The ideas and concepts of the knowledge society are not new. The economist Friedrich A. Hayek (1945) developed a key tenet of “joint knowledge” as a primary factor in an evolving society, describing how “a solution is produced by the interactions of people each of whom possesses only partial knowledge” (530). Leading management expert Peter Drucker (1967) describes a “knowledge organization” as the central reality of modern society, employing knowledge workers that produce ideas and information.

In order for arts organizations to survive and thrive in the knowledge society requires a new way of thinking and operating. The increasing scope and amount of information available to people and organizations have reached a level where many organizations cannot keep up. It is no longer effective to make decisions based solely on a combination of anecdotal information, intuition, and speculation. Today’s arts leaders will need to leverage new sources of data and technology-driven tools to build capacity, serve constituents, secure funding, and ensure success. Achieving this requires a knowledge-centric organization.

The Knowledge-Centric Organization: Understanding Data, Information, and Knowledge

A knowledge-centric organization is one in which multiple people, departments, and programs can use collective knowledge to advance organizational goals (Crawford, Hasan, Linger, and Warne 2009). A knowledge-centric organization creates a culture of learning and views knowledge as an institutional asset. Knowledge-centric organizations are able to gather and leverage disparate sources of data and information, and make knowledge a core value. More important, a knowledge-centric organization is not dependent on size, industry, or corporate structure but is an organizational philosophy and approach that will improve an organization’s ability to survive and thrive in a knowledge society.

In order to understand how knowledge is created and managed within an organization, it is important to understand the relationships between data, information, and knowledge. These terms are often used interchangeably but are understood to be very distinct business terms each with specific uses (Davenport and Prusak 2000) as follows:

- DATA — Discrete facts and figures about objects, persons or events;

- INFORMATION — The analysis, processing, or classifying of data;

- KNOWLEDGE — The distillation of information to incorporate experience, values, insight and intuition.

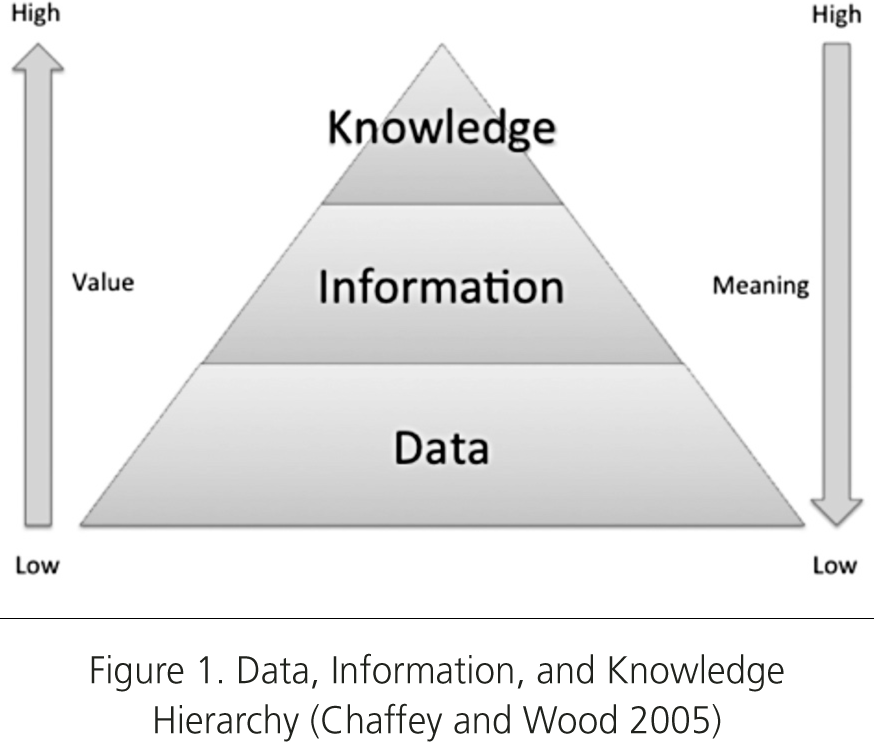

This linkage of data, information, and knowledge is often described as a hierarchy wherein data create information, which in turn creates knowledge. In the hierarchical model, value and meaning are increased when moving from data to information to knowledge. Another common model shows the relationship as a linear progression, treating data, information, and knowledge as a continually moving process rather than a hierarchy of diminishing amounts. Figures 1 and 2 show these two common models.

The key challenge facing arts organizations is that many organizations are not able to gather, collect, or report on even the fundamental data needed to inform their decision making. Without such basic data, the information and knowledge necessary to become a knowledge-centric organization cannot be created and the models in Figure 1 and 2 do not apply. The primary barriers to this include a lack of internal capacity, leadership that does not embrace the use of technology and metrics, and a compartmentalized staffing structure that inhibits sharing and collaboration. These barriers are further exacerbated by an overall lack of data-driven mindsets in many arts organizations (Manyika et al. 2011). Overcoming these challenges will provide organizations with the ability to address the continually changing and evolving social and economic landscape.

Knowledge-centric arts organizations must exhibit the flexibility and agility needed to use collective information to make quick and informed decisions (Crawford et al. 2009). Despite seemingly large barriers, the potential benefits are clear, and today’s arts leaders must strive to overcome them. The information that can be gleaned from access to and analysis of a growing wealth of data can help the leadership of organizations from both an internal and external perspective. Reliable and timely information can ensure that staff and leadership better understand their organizations’ internal operations and external impact by providing the crucial metrics necessary to assess and evaluate performance. Furthermore, this information can help broaden the understanding of an organization’s fit within the communities it serves, providing benchmarks and comparisons to other organizations. This new information can help organizations better communicate their value and impact to the constituencies they serve.

Becoming a Knowledge-Centric Arts Organization

Despite the barriers to full engagement in the knowledge society, arts leaders and organizations can engage in specific practices to ensure success. The concepts of creating a knowledge-centric organization are common in a variety of industry and nonprofit sectors, and best practices have begun to emerge. These best practices are fundamental and involve both people and processes. For arts organizations, the exploratory interviews found three important practices that are needed to build a knowledge-centric arts organization: (1) taking an incremental, data-driven approach; (2) beginning to leverage “Big Data”; and (3) building knowledge by building capacity.

Taking an Incremental, Data-Driven Approach

A fundamental building block of becoming a knowledge-centric organization is the use of data and information to create knowledge. Established organizational theories (Choo 1996) show that an incremental approach can help an organization take the steps toward becoming knowledge-centric. This begins with the organization’s seeking and collecting basic, internal data that can be used to make routine, strategic decisions for internal, operational purposes. The next incremental step is to begin gathering new, external data on constituents, stakeholders, and environmental factors to build a common understanding of the organization’s current state. And finally, the organization can routinely gather and analyze many forms of data and information to improve programs, services, and organizational processes.

This incremental approach is important to the arts and cultural sector as it seeks to address critical issues of audience engagement, funding, and efficient operations. It can ensure that gradual yet continual progress is made in the move toward a knowledge-centric organization. It can also reduce the potentially overwhelming state in which some organizations find themselves when attempting to initiate the process of gathering and collecting data. This stepwise approach can help organizations prioritize the data needed based on their current organizational capacity.

Beginning to Leverage “Big Data”

Taking an incremental, data-driven approach to decision making will then allow arts organizations to benefit from massive amounts of data that are readily available. The term Big Data has emerged to describe not only the sheer volume but also the scope of data that surrounds us. Once organizations are able to collect and analyze their fundamental data, they can take the steps necessary to leverage the power of bigger and broader data. Big Data from public agencies, social media, GIS-based mapping tools, and other services are freely available and can help organizations understand their current environment and stakeholders, and assist in the development of new, fact-based strategies. It’s important that organizations undertake the necessary steps to leverage these data before the knowledge gaps become too large to overcome.

Building Knowledge by Building Capacity

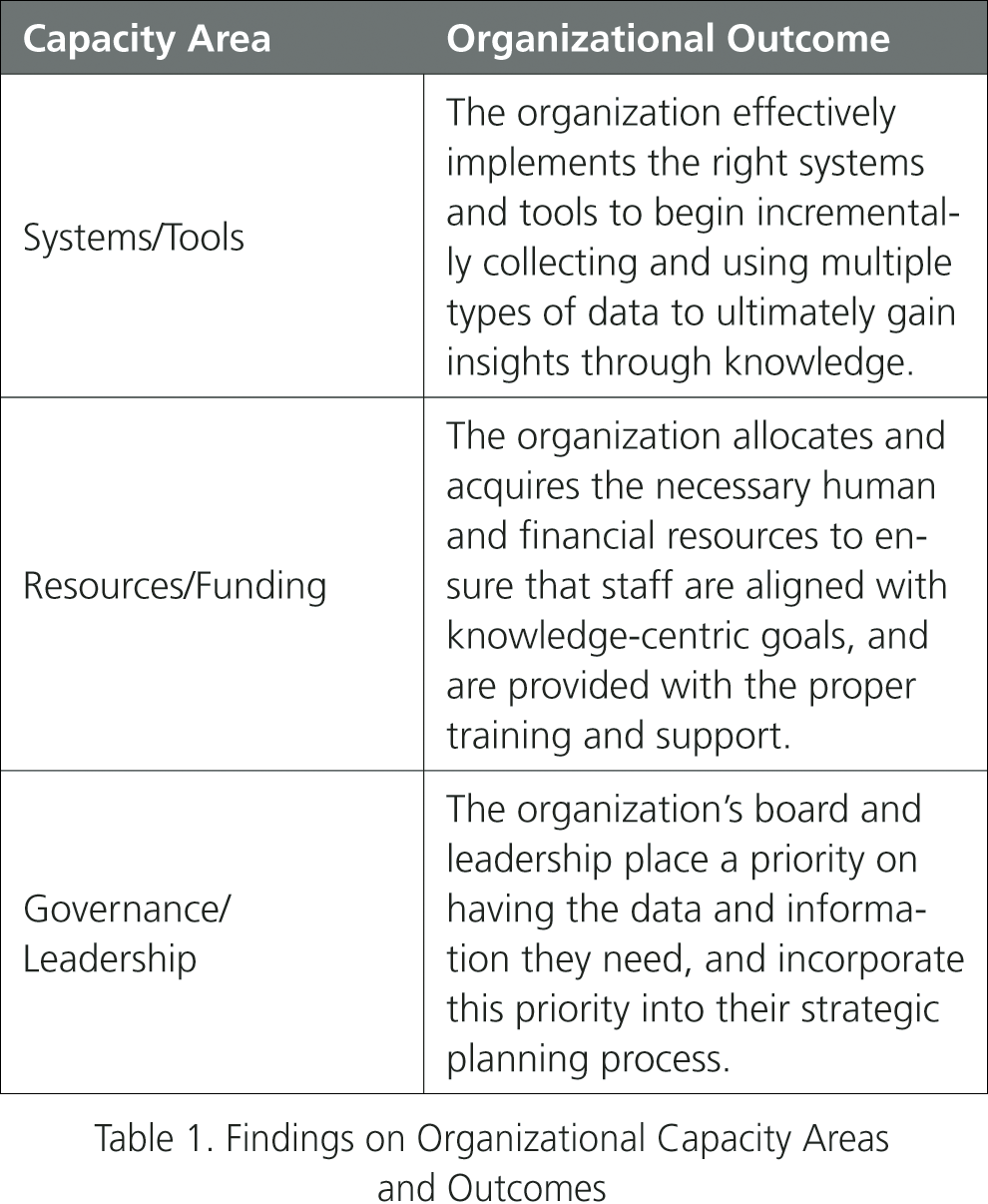

While many arts organizations understand the challenges they face, it has become clear that there is no single approach that will help them become knowledge-centric. It is easy to simply blame a lack of technology, a lack of funding, or a lack of leadership as the reason why an organization is not taking the steps necessary to become knowledge-centric. However, the exploratory interviews found that three specific areas of an organization’s capacity must be developed in order for that organization to become knowledge-centric. Furthermore, an outcome-based approach in these three areas could ensure that organizations are ready to become knowledge-centric. These three areas and related outcomes are shown in Table 1.

Taking an outcome-based approach will help arts organizations focus on the overall organizational change they wish to seek rather than struggle with discrete or tactical approaches.

Gradual Progress toward the Knowledge-Centric Arts Organization

Despite the seeming challenges in becoming knowledge-centric, the arts sector is making gradual yet steady progress. The interviews showed that some arts organizations are beginning to see value in the use of data-driven decision making and acknowledge the fact that their current methods and approaches need to be revised. While still in its early stages, arts organizations and their leaders are beginning to embrace the concepts needed to be part of the knowledge society. It is important that this progress accelerates and reaches a broader scope of organizations, thereby ensuring a thriving arts sector.

The two key drivers of this progress that were observed are the emergence of new tools tailored to the field as well as the emergence of a new generation of arts leadership that is less focused on ideology and more focused on results and impact (Gowdy, Hildebrand, La Piana, and Campos 2009). In recent years, advances in technology have led to the development of several arts-specific tools that can help organizations on their pathway to becoming knowledge-centric. These tools help gather and collect various sources of data and information and analyze the data in ways that build organizational learning. Simultaneously, as a new generation of arts leaders emerges, they are often imbued with strong skills in utilizing technology to achieve organizational goals. These leaders do not have the same aversion toward technology-based tools and are more inclined to seek quantifiable results and demonstrated impact (Gowdy et al. 2009). Both the emergence of arts-focused, knowledge-building tools and new leadership in the field are positive indicators for the knowledge-centric arts organization.

The Critical Role of Grantmakers

Just as arts organizations need to take the steps necessary toward becoming knowledge-centric, grantmakers need to adapt their strategies to help build knowledge-centric organizations. It is only when both efforts align that the sector can sustain itself.

Seven key grantmaker approaches were identified to support the development of knowledge-centric organizations. These approaches, summarized below, all support the needs of arts organizations in their efforts to become knowledge-centric.

Investing in Solid Business Models, Not Organizational Structures

What’s most important for an arts organization is delivering on the promise of its mission. Grantmakers should help organizations understand the processes by which they create and deliver value to their stakeholders, which is accomplished through their business models. This would allow organizations to understand their business models in a comprehensive manner, refine them to deliver maximum impact, and let the business model drive the organizational structure rather than the other way around. A key role for grantmakers in this strategy is to support the fundamental gathering of basic business data and metrics that can help an organization fully understand its business model, including how the model may need to change.

Creating “Knowledge Capital”

As the issues relating to capitalization in the arts and cultural sector gain prominence and grantmakers gradually begin to address the prevalence of miscapitalization, a key finding is that a new type of capital funding could help ensure arts organizations have the resources needed to become knowledge-centric. Grantmakers should invest in “knowledge capital,” a form of capital funding specifically tailored to increase an organization’s ability to implement the three core knowledge-centric practices cited previously. When knowledge capital is effectively provided it could have the potential to ensure years of stability and sustainability. This new form of capital could be used to invest in infrastructural systems that build efficiency; to provide consistent professional training to current staff; to hire new staff members with the necessary technical and analytical skills; and to engage with outside expertise to provide insights into best practices from beyond the arts and cultural sector.

Supporting Sensible Scaling (Up and Down)

The concept of scaling in the arts sector is often met with resistance. The traditional response to the issue is that an art form cannot be scaled (i.e., it will always take four musicians to compose a string quartet). However, what can be scaled, up or down, is the infrastructure that delivers the artistic product. If an organization or program is successful, how can it reach more people or generate more revenue? What elements of its infrastructure can be made more effective to allow this? How can technological solutions build efficiencies? Grantmakers should seek to fund operational growth opportunities from proven successes that are readily scalable. Without this type of investment from grantmakers, growth opportunities are missed. Conversely, grantmakers should support a methodical scaling down of organizations or programs that are reaching diminishing audiences or experiencing reduced demand. This can range from funding a “right sizing” process to helping support a graceful closing.

Funding (Faster) Failure

The concept of failure in the arts sector is often unique when compared to more innovative sectors, where failure is a common, accepted practice. In the arts, failure is often quietly dismissed with little effort to learn from what went wrong. In some cases, grantmakers also feed into this problem by encouraging risk but not accepting failure as a potential outcome. In fact, grantmakers should acknowledge that failure is always a potential outcome and is part of any venture. Grantmakers should help organizations take the time and effort to evaluate failure and use the lessons learned to inform future actions, thereby creating knowledge. Grantmakers should also acknowledge that failure can often help an organization move forward more effectively, building off lessons from the past. As Samuel Beckett eloquently states, “Try again. Fail again. Fail better” (1984).

It’s Not (Just) about Technology

While many grantmakers are willing to fund technology tools and systems, which address a vital need in many organizations, it’s important to understand that these tools and systems are a means and not an end toward a knowledge-centric organization. In fact, rapid advances in many types of data collection, reporting, and analysis tools have eliminated many of the direct cost barriers originally faced. A key role for grantmakers is to invest in the effective selection of the tools and systems that best serve an organization’s needs, combined with extensive support for the appropriate training, implementation, and ongoing management necessary for organizations to truly benefit from efficient and effective systems.

Providing the Proper Personnel

Too often, arts organizations are unable to recruit, hire, and train staff with the skills needed to build a knowledge-centric organization. Many organizations delegate critical data gathering and analysis tasks to staff members who are not skilled or already overtasked, resulting in missed opportunities to create knowledge from data and information. Grantmakers should ensure that organizations have the appropriate resources allocated to data, information, and knowledge generation through investing in specialized staffing. It is no longer acceptable for an organization to lack staff with critical analytical skills, and grantmakers can intervene to support hired or contracted expertise.

Collaborating and Cooperating

Just as it’s vital that arts organizations find ways to collaborate on programmatic activities that can offer mutual benefits, grantmakers can collaborate to support knowledge-centric practices in arts organizations. This can be accomplished not only by sharing funds but also by sharing expertise and contacts. A collaboration of grantmakers could collectively address the organizational capacity issues needed for an arts organization to become knowledge-centric, rather than individually attempting to support potentially conflicting activities. Grantmakers should have open and honest conversations among themselves as well as with grantees on how to collectively build knowledge in a manner that positions grantees for long-term success.

All these suggested approaches, while somewhat broad, could provide a framework for grantmakers to collectively work toward creating a knowledge-centric arts sector. An important finding in this area is that a small number of grantmakers have already begun to undertake some of these approaches. While not all grantmakers (particularly public agencies) are able to rapidly change grantmaking approaches, grantmakers should investigate how these approaches can become incorporated into their strategies.

Conclusion and Implications

As many nonprofit arts organizations continue to face challenges in their ability to remain sustainable and relevant, it’s important to put these challenges in the context of our knowledge-based society and develop approaches that will help to ensure a healthy, stable sector. Arts organizations must become knowledge-centric, by using knowledge to advance their missions and goals, gathering and leveraging disparate data and information, and creating a culture where knowledge is a core value. Likewise, grantmakers have a symbiotic relationship with arts organizations, and they must adapt their approaches and strategies to align with the need to build knowledge-centric arts organizations.

Arts organizations need to begin taking the incremental approaches necessary to become more data driven in their decision making and operations. This effort can then guide organizations in embracing the growing wealth of “Big Data” and the resulting information and knowledge it provides. In turn, this can help strengthen capacity in the areas of governance and leadership, resources and funding, and systems and tools.

Grantmakers are in the unique position to help the arts and cultural sector push through the disruptive transitions that are part of the process to become knowledge-centric organizations. By collectively undertaking new approaches that are aligned with the needs of arts organizations, a stronger, more resilient sector will emerge. Grantmakers should invest in and support these approaches in a holistic, structured manner to prepare our field to be active participants in the knowledge society.

Note

- Summary of methodology: This research project combined an extensive literature review; exploratory interviews and conversations with leadership of a small group of arts organizations; reviews of grantmaking practices and documents; and prior and current professional experience and employment working within arts organizations and grantmaking entities. This research comprises a growing body of my ongoing work in the areas of knowledge-centric arts organizations, technology, and innovation.

References