Audiences at the Gate

Reinventing Arts Philanthropy through Guided Crowdsourcing

Spurred on by technological advances, the number of aspiring professional artists in the United States has reached unprecedented levels. The arts’ current system of philanthropic support is woefully underequipped to evaluate this explosion of content — but we believe that the solution to the crisis is sitting right in front of us. Philanthropic institutions, in their efforts to provide stewardship to a thriving arts community, have largely overlooked perhaps the single most valuable resource at their disposal: audience members.

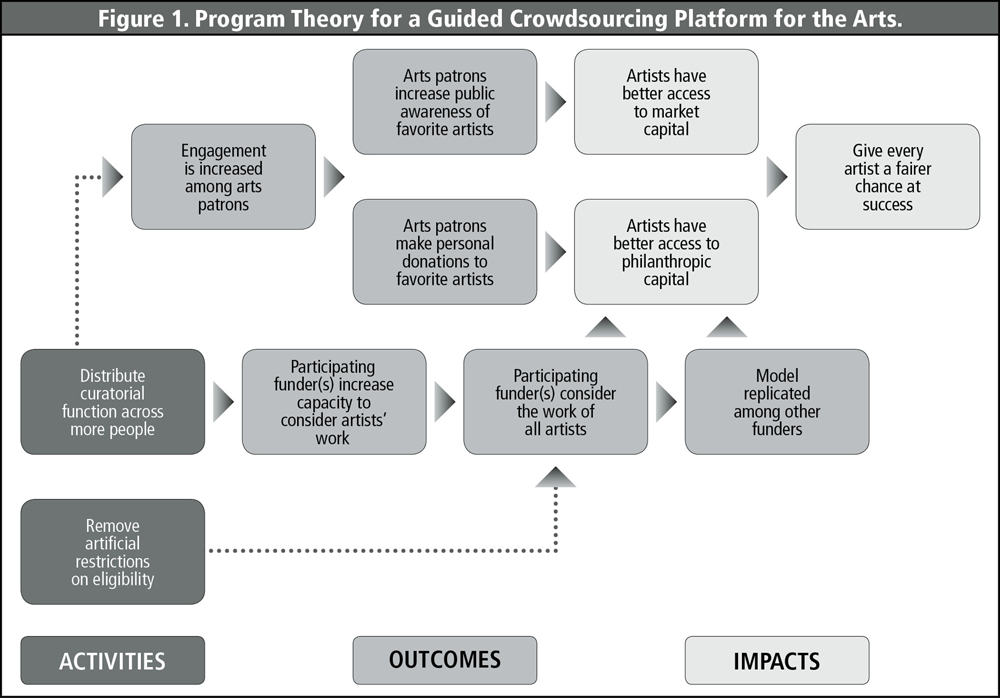

We contend that by harnessing the talents of the arts’ most knowledgeable, committed, and ethical citizens and distributing funds according to the principles of what we have termed guided crowdsourcing, grantmaking institutions can increase public investment in and engagement with the arts, increase the diversity and vibrancy of art accessible to consumers, and ensure a more meritocratic distribution of resources. We envision an online platform that empowers aficionados, aspiring critics, and curious minds to participate in the philanthropic process — a forum with the potential to give fair consideration to the full range of artistic talent available and ensure that the most promising voices are heard and amplified.

Choking on the Fire Hose: The Arts’ Capacity Catastrophe

— Theater director, age 30

An Embarrassment of Riches

In the United States, more than two million working artists identify their primary occupation as an arts job. 2 And the ranks of those who create art, whether or not they earn any money from it, ballooned to some twenty million adults in 2008. 3 Many of those in this latter category fall under the rubric of what Charles Leadbeater and Paul Miller have called “Pro-Ams,” serious amateurs and quasi professionals who “have a strong sense of vocation; use recognized public standards to assess performance; . . . [and] produce non-commodity products and services” while “spend[ing] a large share of their disposable income supporting their pastimes.” 4 Thanks to historically inexpensive production and distribution technology, more artistic products can reach more people more easily than ever before: as of April 2012, for example, users were uploading the equivalent of two thousand full-length movies to YouTube every hour. 5

The human brain — not to mention the human lifespan — simply cannot accommodate a considered appreciation for so many contenders for its attention. Even if a music lover kept his headphones on for every minute of every day for an entire year, he wouldn’t be able to listen to more than about a sixth of the seventy-seven thousand albums that were released just in the United States in 2011. 6 Because we could not possibly sample every artistic product that might come our way, we must rely on shortcuts. We may look for reviews and ratings of the latest movies before we decide which ones we’d like to see. We often let personal relationships guide our decisions about what art we allow into our lives. And we continually rely on the distribution systems through which we experience art — museums, galleries, radio stations, television networks, record labels, publishing houses, and so on — to narrow the field of possibilities for us so that we don’t have to spend all our energy searching for the next great thing.

Every time we outsource these curatorial faculties to someone else, we are making a rational and perfectly defensible choice. And yet every time we do so, we contribute to a system in which those who have already cornered the market in the attention economy are the only ones in a position to reap its rewards.

The Arts’ Dirty Secret

We regard the market’s lack of capacity to evaluate the full range of available art as a systemic and rapidly worsening problem in the arts today. Artists take time to learn their craft and capture attention; while the market may support an “up and coming” artist to maturity if she is lucky, making the transition to “up and coming” requires nurturing that the market will not provide. Before an artist becomes well known, the “market” she encounters is not the market of consumers but rather the market for access to consumers. This market is controlled by a small number of gatekeepers — for example, journalists, artistic directors, gallery owners — who each face the same capacity problems described above. Even the most dedicated and hardworking individuals could not possibly keep up with the sheer volume of material demanding to be evaluated.

This tremendous competition for gatekeepers’ attention frequently forces aspiring artists to assume considerable financial risk even to have a shot at being noticed. An increasing number are receiving preprofessional training in their work; degrees awarded in the visual and performing arts jumped an astonishing 71 percent between 1997 and 2009. 7

Others are starting their own organizations; the number of registered 501(c)(3) arts and culture nonprofits rose 48 percent over the past ten years. 8

Yet all of this increased training and activity comes at a steep price, one all too often borne by the artist herself. Master’s degrees at top institutions can set her back more than $50,000 per year; 9 internships that could provide key industry connections are frequently unpaid. Artists in the field have been known to incur crippling consumer debt in pursuit of their dreams: the cocreators of the award-winning film documentary Spellbound, for example, maxed out fourteen credit cards to finance production. 10 Indeed, a daunting investment of direct expense and thousands of hours of time not spent earning a living are virtual requirements to develop the portfolio and reputation necessary to translate ability into success. However one defines artistic talent, it is clear that talent alone is not enough to enable an artist to support herself through her work.

— Composer, age 27

If gatekeepers lack the capacity to identify and provide early support to artistic entrepreneurs with little pedigree but plenty of potential, there is a real concern that to compete for serious and ongoing recognition in the arts is an entitlement of the already privileged. For a sector of society that often justifies subsidy by purporting to celebrate diverse voices and build bridges between people who see the world in very different ways, this is a grave problem.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Grantee

Grantmaking institutions have a critical role to play in the market for access. Grants represent a very different kind of support from sales of tickets, stories, or sculptures. They may be crucial for demonstrating proof of concept for a new venture — or simply for the development of a style, portfolio, and audience. Most important, they provide a temporary financial cushion that can allow the artist-entrepreneur to manifest her true vision rather than see it continually undermined by scarcity of equipment, materials, staffing, or time. Grants can make the difference in production values that ensure a serious reception from critical eyes and ears, and allow the artist an opportunity to use time that might otherwise need to be spent earning income to perfect and promote her work. In short, grants are a seemingly ideal vehicle through which to address the fundamental inequities created by the pinched market for access.

— Jazz musician, age 34

Sadly, the lack of evaluative capacity biases the philanthropic market for the arts just as it skews the commercial market. In a perfect world, foundation and agency employees would have the time and money to find grantees by continually seeking out and experiencing art in its natural habitat. In the real world, a notoriously small number of staffers at a given foundation or panel of experts from the community are often hard pressed simply to review all of the art that comes through the door.

Not surprisingly, then, grantmakers take defensive measures to protect against being overwhelmed by an inundation of requests. First, they explicitly narrow their scope through eligibility restrictions. Nearly 45 percent of foundations that support the arts refuse to accept unsolicited applications at all, and even those that do frequently consider applications only for particular art forms, geographic regions, types of artist, or types of project. 13 Until 2009, to cite an especially dramatic example, the Judith Rothschild Foundation in New York only made “grants to present, preserve, or interpret work of the highest aesthetic merit by lesser-known, recently deceased American [visual] artists.” 14 Many grant programs additionally refuse to consider organizations without a minimum performance history or a minimum budget level, and a majority will not award funds directly to individuals, for-profit entities, or unincorporated groups.

Funders also narrow their scope implicitly through their selection process. The selection is usually made by some combination of the institution’s staff, its board of directors, and outside experts serving as grant panelists. Because so few individuals are involved in the decision-making process, triage strategies are unavoidable. Application reading may be divided among the panel or staff, with the result that only one person ever reads any given organization’s entire proposal. When work samples are involved, artists’ fates can be altered forever on the basis of a five-minute (or shorter) reception of their work. 15

These coping mechanisms are perfectly understandable, given the sheer volume of art produced and imagined. But the unfortunate result is that institutional money is distributed with hardly more fairness than commercial money — and this is especially troublesome because of institutional grantmakers’ power beyond their purses as outsourced curators of other funding streams, including, ultimately, the commercial market. After all, for most individual donors and consumers alike, the art that they even have a chance to encounter is likely to be art that has already passed the muster of multiple professional gatekeepers. The capacity problem that hampers grantmakers’ ability to choose the most promising artists in an equitable way thus compounds itself as it reverberates through the rest of the artistic ecosystem.

The shortage of capacity and its consequences on the diversity, liveliness, and brilliance of the arts world are not going away. With digital distribution networks making it easier than ever to put creative work in the public eye, the defensive mechanisms that funders employ to limit intake are only going to become more and more strained. A solution is needed, fast. Fortunately, there is a cheap, practical, and responsible way for institutions to better cope with their lack of evaluative capacity.

Calling for Backup: Crowdsourcing (to) the Rescue

Typically, institutions select the members of their staffs and grant panels on the basis of passion for and experience with the arts, on the theory that these qualities lead to discerning judgments about the merit of applicants. But such traits are by no means limited to this narrow group. Tapping the thousands of dedicated and knowledgeable devotees of specific art forms who engage in robust discussion of the arts every day would allow foundations and agencies to go a long way toward addressing their own capacity problems — and toward opening access to grant funds to a broader range of deserving artists.

Our proposal draws inspiration from the phenomenon of crowdsourcing. Crowdsourcing has its roots in the open-source software movement, which designed and built complex applications through the collaboration of anyone with the time, interest, and ability to contribute to a project. Rather than relying on a handful of experts, crowdsourcing enlists dozens, hundreds, or thousands of people to do the work — and, in its purest form, to ensure the quality of the end result.

Arts philanthropy has already begun tapping into the power of crowdsourcing, most notably through the “crowdfunding” model used by websites like Kickstarter and the “voting without dollars” model used by corporate programs such as Chase Community Giving. While both models help engage wider participation in arts philanthropy, we believe that neither fully taps the power of crowdsourcing to address the problem of gatekeeping capacity. There is a path not yet taken in the arts that can better harness dispersed talent and build robust community: what we call “guided crowdsourcing,” exemplified by websites like Wikipedia and Stack Overflow.

Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding for artistic projects has blossomed in recent years, as platforms such as Indiegogo (2008), Kickstarter (2009), USA Projects.org (a program of US Artists) (2010), RocketHub (2010), PleaseFund.Us (2011), and Power2Give.org (2011) have joined the pioneering album-label-cum-crowdfunding-site ArtistShare (2003). 16 These websites create online philanthropic marketplaces for individual donors, aggregating often modest gifts to fund larger projects. Artists or arts organizations create online profiles or pitches describing a creative project and the amount of money they need to pursue it; users support work(s) in progress they find compelling, typically in exchange for access to the artistic process, merchandise, or other tokens of appreciation.

Kickstarter, the largest and best known of these sites, has proved remarkably successful as a fundraising platform for creative projects in the arts, design, games, publishing, and technology. The site processed $99 million in 2011 and is on track to distribute more than $150 million this year — which has prompted controversial comparisons to the NEA’s $146 million budget. Four projects, including a web-based comic book, have raised more than $1 million each. And the impact on the arts themselves is already significant: in the high-cost medium of moviemaking, for example, Kickstarter donors supported thirty-one films at this year’s SXSW festival in Austin and seventeen films at Sundance. 17

Crowdfunding has brought a few clear benefits to arts philanthropy. First, the sites facilitate solicitation for smaller donations, making it easier for individual artists to leverage their social networks and aggregate modest giving into significant funding. Second, it is reasonable to assume that some portion of the money pledged through sites like Kickstarter represents new money for the arts, provided by donors who are motivated by the convenience and/or viral nature of the medium to give more or more often than before. Third, the sites provide a forum for interaction between artists and possible donors and audiences, potentially engaging fans in a project more deeply than is usually possible offline.

But these online donor marketplaces fall short of the full potential of crowdsourcing for arts philanthropy, in part because they use the same tools as the market and traditional philanthropy to cope with the lack of capacity to evaluate art. This can work in two ways. Some sites, like USA Projects, explicitly use traditional gatekeepers to restrict the number of projects available on the site: artists are eligible to post a project only if they have received an award or residency from the site’s “growing list of distinguished arts organizations around the country.” 18 Others, like Kickstarter itself, exercise little editorial discretion over which projects are posted. 19 This effectively creates an open marketplace for artistic support — but it doesn’t solve the problems with such a market discussed previously. A would-be donor confronted by the 27,086 projects on Kickstarter in 2011 may poke around the site a bit and stumble across something entirely new he wants to support, but more likely he will rely on guidance from gatekeepers (such as media sources or Kickstarter’s own staff) to choose projects. There is little incentive for him to browse unfamiliar proposals endlessly without some deeper reward for doing so, especially if he has limited funds to donate. 20

More important, supporting a project on these sites is much like supporting a project in real life: you vote with your own dollars. Accordingly, the most fair-minded, informed, and thoughtful critics — the people best able to assess the long-term value of cultivating a given artist or organization — have no more influence than a casual browser or a relative of the artist with the same amount of disposable income. Crowdfunding sites thus fundamentally resemble the commercial marketplace, doing little to address the systemic inequities that pervade the market for access to consumers.

Voting without Dollars

An alternative model of crowdsourced philanthropy that enjoyed a period of popularity recently allows individuals to exert influence on how other people’s philanthropic contributions are spent. These are typically marketing initiatives by corporations that leverage social media to engage large numbers of consumers in decisions about which causes to fund in order both to do good and to build brand equity. In 2010 and 2011, JPMorgan Chase, PepsiCo, and American Express launched the highest-profile examples of this trend. For example, in March 2011, JPMorgan Chase committed to distributing $25 million over two years to nonprofit organizations through its Chase Community Giving program, which awards grants based primarily on the votes of Facebook users. 21

These programs may bring incremental funding to the arts that would otherwise go into less beneficent forms of corporate marketing — for example, Pepsi launched its Refresh Project in 2010 using its Super Bowl ad budget. 22 They may also involve broader audiences in supporting early-stage art (and other philanthropic) projects, although that support is likely to be limited in most cases to clicking a “like” button to vote for a project. But the voting without dollars model does little to leverage crowdsourcing to benefit the arts. Like crowdfunding sites, they lack a mechanism to identify and amplify critical talent in selecting projects to support. What’s missing from sites like Kickstarter and these corporate crowdsourcing programs is expertise: anyone can participate equally, regardless of how knowledgeable they are or how thoughtfully they evaluate proposals. Indeed, one frequent criticism of these models is that a “one person, one vote” or social-network-based approach to philanthropy can all too easily degenerate into a popularity contest with little connection to the merit of the potential recipients. This is in keeping with the corporate objectives of the programs, which depend on reaching the largest audiences possible rather than the most informed, but it means that arts dollars are awarded not necessarily to the most promising artists but to those with the best connections, the most marketing savvy, or the most time to canvass for votes. 23

Guided Crowdsourcing: Harnessing Expertise and Building Community

The very best examples of crowdsourcing — the ones that illustrate the potential of the concept at its fullest — identify and empower the members of the community with the most talent and dedication, fostering an open yet meritocratic hierarchy that promotes an environment of shared opportunity and responsibility. We call this model guided crowdsourcing. So far, it has not been explored in depth by philanthropists, arts-focused or otherwise, but it has been developed robustly elsewhere in ways that can serve as a model for the arts.

Founded in 2001, Wikipedia is perhaps the oldest and most famous large-scale example of guided crowdsourcing on the web. As anyone who has conducted research online knows, Wikipedia has drawn on the knowledge and editorial acumen of a huge pool of often anonymous volunteers to create and maintain a living encyclopedia composed of some twenty-one million entries in 285 languages. 24 Despite individual cases of absurd errors or deliberate fraud, a major study in Nature found that its entries were only slightly less accurate than those of Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (Encyclopædia Britannica, which has since ceased publishing its print edition, disputed some of the findings.) 26

To maintain the crowdsourced content, Wikipedia relies on a fiercely dedicated user community that has self-organized into a meritocracy. 27 Though the site is open to editing and revision by anyone, a small army of experienced volunteer “administrators” boast additional powers, such as the ability to make edits about living people. 28 These users are chosen by “bureaucrats,” who themselves are selected by community consensus, and disputes among editors are resolved by a volunteer-run Arbitration Committee. 29 These responsibilities not only keep the community’s most passionate members fully engaged, they also put them to work to improve the community and its project.

The success of Wikipedia has helped inspire large-scale guided crowdsourcing projects in more specialized communities. One particularly relevant example is Stack Overflow, a question-and-answer website for computer programmers on which anyone can ask or answer questions. The site incorporates expertise through a carefully designed reputation algorithm that measures how much the system “trusts” a user and emphasizes information from the most trusted members of the community. The allocation of reputation is itself crowdsourced: users accrue reputation points when their answers, questions, or edits are voted helpful by others. These reputation points unlock “privileges,” such as the right to vote an answer helpful, edit questions, or flag answers for deletion, and “badges,” such as “Guru” for providing many helpful answers or “Vox Populi” for voting on the helpfulness of forty answers in a day, the most allowed by the site. This system of points and privileges is an example of “gamification,” the use of the same neurological reward system that makes video games so addictive to increase engagement in an online community, and it has helped Stack Overflow attract more than a million users — including 6,500 Gurus — since its founding in 2008. 30

Taking our cue from these successful efforts to design a system to privilege the best qualities of the participants in a community, we propose a new model of arts philanthropy — one that matches the explosion of artistic content with an explosion of critical acumen to evaluate it.

Philanthropy’s Finest: The Pro-Am Program Officer Paradigm

To leverage the critical faculties of passionate arts lovers and address the problem of evaluative capacity, we propose the creation of an online grants management platform that simultaneously serves as a social network, multi-media showcase, and marketplace for individual donors. One or more funding agencies could spearhead this platform, which we will call the Gate for simplicity, by redirecting a portion of their grantmaking budgets through it. A sophisticated set of algorithms would empower the website’s community to identify the most qualified and dedicated voices among its own ranks and elevate them to increased levels of influence on a continually renewing basis. In this way, those whose artistic judgments carry the most weight will have earned that status from their peers and colleagues.

How It Works

The process begins when an artist or artist-driven organization (nonprofit or otherwise) applies for a general operating support grant through the Gate — all forms of art are welcome. Rather than being sent to a foundation’s program officer for review, the applicant’s materials — proposal narrative, samples of the artist’s work, a list of upcoming events or classes open to the public — are posted online as part of each applicant’s public profile on the site.

Members of the public will also be invited to join. Once registered, they can view materials submitted by grant contenders and share reactions ranging from one-line comments to in-depth critiques. In order to jump-start the conversation, ensure an initial critical mass of reviewers, and strike a constructive and intelligent tone, it will be important to reach out in advance to knowledgeable arts citizens (perhaps including some of the very gatekeepers mentioned earlier who might otherwise serve on grant panels) to encourage their participation. The goal is to engage a broad range of art lovers in a robust conversation about the proposals under review — and about the arts more generally — thereby ensuring a better-considered distribution of grant money. 31

Of course, not all commentators will make equally valuable contributions to the discussion. Just like making art, providing critical analysis and consistently thoughtful, informed, and credible feedback requires considerable skill and practice. In short, we want to be able to open up the process to anyone without having to open it to everyone. What qualities would we desire in those who influence resource allocation decisions in the arts? Certainly we would ask that our critics be knowledgeable in the fields they review. We would also want them to be fair — not holding ideological grudges against artists or letting personal vendettas influence their judgment. We’d want them to be open-minded, not afraid to dive into unfamiliar or challenging territory when the time comes. And finally, we’d want them to be thoughtful: able and willing to appreciate nuance, and mindful of how what they are experiencing fits into a larger whole.

Technology now allows us to systematically identify and reward these qualities in a reviewer. On the website, a reviewer increases her “reputation score” by winning the respect of the community. Each user can rate individual comments and reviews based on the qualities outlined above; higher ratings increase a reviewer’s standing. To keep the conversation current and make room for new voices, the ratings of older reviews and comments will count for less over time. In addition to peer acclaim, the reputation algorithm can also reward seeking out unreviewed proposals and commenting on a breadth of submissions. A strict honor code will require users to disclose any personal or professional connections to projects they review, with expulsion the penalty for violators. Reviews suspected of being at odds with this policy can be flagged for investigation by any site user, and the site’s administrators will take action where deemed appropriate.

Every quarter, program staff from each grantmaker participating in the Gate will review the reputation scores of community members and choose a crop of users to elevate to Curator status for that grantmaker. Selection will be based primarily on peer reviews, but the staff will have final say and responsibility over who is given this privilege. A clear set of guiding principles will be developed and shared by each grantmaker to ensure that the choice is as fair and transparent as possible. A curator receives an allowance of “points” from the grantmaker who selects him, which he can then distribute to various projects on the site in accordance with the discipline or area of the Curator’s expertise. Curators are identified by (real) name to other users so as to foster a sense of accountability, and their profiles show how they have chosen to distribute their points. So long as a Curator maintains a minimum reputation score by contributing new high-quality reviews, he will continue to receive new points each quarter.

As a project accumulates points from Curators, it receives more prominent attention on the site. It might show up earlier in search results, appear in lists of recommendations presented to users who have written reviews of similar projects, or be highlighted on the home page. But since Curators maintain their reputation (and aspiring Curators gain their reputation) in part by reviewing proposals that have failed to attract comments from others, the attention never becomes too concentrated on a lucky few.

When it comes time to award the grant dollars allocated by each supporting grantmaker, the collective judgment of that grantmaker’s Curators is used as the groundwork for the decision-making process. This approach ensures that organizations cannot win awards simply by bombarding their mailing lists with requests for votes or donations, because the crowd exerts its influence indirectly through Curators selected on the basis of sustained, high-quality contributions. While it is still ultimately the responsibility of a grantmaker’s board of directors to choose recipients, we anticipate that adjustments will be made only in exceptional cases — that, essentially, the heavy lifting will have been done by the crowd.

Meanwhile, the very best contributors — the stars of the site — could be engaged by grantmakers on assignment to see and review specific public events in their area associated with proposals on the site. Their reviews would be highlighted prominently to give their expert work maximum exposure. That system would allow funders to send trusted reviewers to distant events without exorbitant travel costs; meanwhile, the writer would receive a financial incentive for exceptional ongoing service to the site and the arts community.

Of course, artists, administrators, and contributors won’t be the site’s only audience. Since work samples will represent an important part of many applications, the platform will also be a convenient way for the public to discover new artists and ensembles, guided by the judgments of a myriad of devotees. Each proposal uploaded will give passersby the opportunity to contribute their own money in addition to any comments they may have — and, unlike Kickstarter, the Gate will give individual donors access to rich, substantive reviews of project proposals. Donors could even have the option of tacking on a small “tip” to each donation to help defray the site’s modest operating costs.

It is worth emphasizing that despite the promise of this model to address a specific gap in the funding ecosystem, we do not anticipate that it will or should supplant the field’s traditional grantmaking entirely. “Leadership”-level awards to major service organizations or institutions with a national profile do not face the same kinds of capacity challenges as grants to smaller producing and presenting entities or individual artists, and may require a greater level of expertise in evaluating factors such as financial health and long-term sustainability than a nonprofessional program officer may be able to provide. Thus, we see this approach as one element in a broader portfolio of strategies to optimally support the arts.

Few good ideas come to fruition without resources, and this one is no exception. The platform should be launched with a substantial commitment (we suggest at least $1 million) from participating funders to signal seriousness of purpose and ensure a meaningful level of support to the artists and organizations involved. Although it would be possible to pilot the system in a limited geographical area or with only certain disciplines at first, the concept can only reach its true potential if a certain critical mass is achieved — enough to make it worth artists’ while to ensure representation on the site and worth reviewers’ while to contribute their time and curiosity to making it thrive. Furthermore, one or more community engagement staff will need to ensure that the ongoing discussion remains frank, thoughtful, and passionate — but not vicious or counterproductive. Such a desirable culture will not develop automatically; fostering it will mean setting and revising rules and procedures; reminding users of the funding priorities established by funding partners and engaging in dialogue about those priorities when appropriate; expelling users who violate the standards of the community; and developing a method to evaluate and report on the grants made through the site, both to the funders and back to the users.

We anticipate that this system will be highly sustainable. Once the infrastructure is in place, the website will be inexpensive to maintain, and may well prove cheaper than more traditional methods of distributing funds. The powerful incentives provided to both artists (access to a source of funding coupled with real-time feedback on their proposals) and reviewers (the opportunity to gain notoriety, influence, and even material compensation for doing something they love) should be sufficient to maintain interest on all sides.

Finally, the greatest beauty of the site is that there is ample opportunity to experiment with various approaches until just the right formula is found. If the original algorithm for calculating reputation scores turns out to be ineffective, it can be changed. If the rules against reviewing the work of friends turn out to be too draconian, they can be adjusted. If one foundation decides it wants to give its Curators actual dollars to distribute instead of abstract points, that is an easy fix. Meanwhile, if the system proves successful, additional funders could be invited to contribute their resources to the pool, making even deeper impact possible.

Conclusion

We expect that, if successful, a guided crowdsourcing platform will result in a more equitable distribution of philanthropic funds that always takes into account the actual work product rather than reputation alone; be based on the opinions of acknowledged leaders in the community who continually earn their standing among their peers; and fairly consider the efforts of far more artists and artist-driven organizations than would be possible otherwise.

While guided crowdsourcing cannot guarantee all aspiring artists a living, by empowering thoughtful consumers of the arts to help decide whose dreams deserve to be transformed into reality, it can provide more equality of opportunity than under the status quo — and guarantee the rest of us richer artistic offerings than ever before.

It’s time to appoint the next generation of arts program officers: all of us.

Daniel Reid is the director of strategic planning at the Hunter College School of Education.

A version of this article appeared in Edward P. Clapp, 20UNDER40: Re-Inventing the Arts and Arts Education for the 21st Century (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2010).

- Anonymous, personal communication, February 21, 2010. All the individuals whose views appear in this article are critically acclaimed emerging artists under forty years of age, and are quoted with permission.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2012–13 Edition, http://bls.gov/oco. This count follows the NEA’s classification of arts-related jobs, which includes radio and television announcers, merchandise displayers, and archivists. National Endowment for the Arts, Artist Employment Projections through 2018 (Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts, 2011). A more restricted definition of arts-related jobs could yield a count of ~1.8 million Americans. For more on this topic, see D. Gaquin, Artists in the Workforce: 1990–2005 (Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts, 2008), p. 1; National Endowment for the Arts, Artists in a Year of Recession (Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts, 2009); and J. A. Davis and T. W. Smith, General Social Surveys: 1972–2008 (Chicago: National Opinion Research Center, 2009).

- K. Williams and D. Keen, 2008 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts, 2009), p. 43.

- C. Leadbeater and P. Miller, The Pro-Am Revolution (London: DEMOS, 2004), pp. 21–22.

- YouTube,“Statistics” (n.d.), http://www.youtube.com/t/press_statistics. This calculation is based on a feature-film length of ~105 minutes.

- Nielsen SoundScan, via BusinessWire, The Nielsen Company & Billboard’s 2011 Music Industry Report (January 5, 2012), http://www.marketwatch.com/story/the-nielsen-company-billboards-2011-music-industry-report-2012-01-05. This calculation is based on a conservative estimate of forty minutes in length per album.

- R. J. Kusher and R. Cohen, National Arts Index 2010 (Washington, DC: Americans for the Arts, 2011), p. 64.

- R. J. Kusher and R. Cohen, National Arts Index 2012 (Washington, DC: Americans for the Arts, 2012), p. 51.

- For example, the three highest-ranked fine arts MFA programs in US News & World Report estimate nine-month costs, including tuition and living expenses, at $55,000–$65,000. US News & World Report. “Top Fine Arts Schools 2013” (n.d.), http://grad-schools.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-fine-arts-schools. See MFA program websites at http://art.yale.edu/TuitionFeesGeneralExpenses, http://www.risd.edu/Financial_Aid/FAQs, and http://www.saic.edu/webspaces/portal/finaid/1213_worksheet_gr.pdf.

- C. Waxer, “No Cash, No Credit, No Movie,” CNNMoney.com (January 21, 2010), http://money.cnn.com/2010/01/21/smallbusiness/sundance_credit_cards/index.htm.

- Anonymous, personal communication, February 20, 2010.

- Anonymous, personal communication, February 22, 2010.

- Foundation Center, “Foundation Directory Online” (n.d.), http://fconline.foundationcenter.org. Only 1.3 percent of arts funders in the database accept applications with no geographic restrictions.

- The Judith Rothschild Foundation, “Grants List” (n.d.), http://www.judithrothschildfdn.org/grants.html.

- NewMusicBox, “Behind Closed Doors: Making an Evaluation” (n.d.), http://www.newmusicbox.org/page.nmbx?id=65fp03.

- Crowdfunding has also become an important trend in philanthropy more broadly: websites like Kiva, DonorsChoose, Modest Needs, and GlobalGiving allow individual donors to contribute to charitable causes and micro-entrepreneurs around the world. See information about each arts crowdfunding program at its website: http://www.indiegogo.com/about/pr/42, http://www.kickstarter.com/help, http://www.usaprojects.org/faq, http://www.rockethub.com/learnmore/intro, http://pleasefund.us/help/press, http://www.power2give.org, http://www.artistshare.com/v4/About.

- C. Franzen, “Kickstarter Expects to Provide More Funding to the Arts Than NEA,” Talking Points Memo, February 24, 2013. Available at http://idealab.talkingpointsmemo.com/2012/02/kickstarter-expects-to-provide-more-funding-to-the-arts-than-nea.php. For an alternative perspective on the comparison to the NEA, see I. D. Moss, “Art and Democracy: The NEA, Kickstarter, and Creativity in America,” New Music Box, April 4, 2012. Available at http://www.newmusicbox.org/articles/art-and-democracy-the-nea-kickstarter-and-creativity-in-america.

- USA Projects, “FAQ.” (n.d.), http://www.usaprojects.org/faq.

- Kickstarter, “2011: The Stats,” January 9, 2012, http://www.kickstarter.com/blog/2011-the-stats.

- Kickstarter, “Frequently Asked Questions: Who Can Fund Their Project on Kickstarter?” (n.d.), http://www.kickstarter.com/help/faq/kickstarter%20basics#WhoCanFundTheiProjOnKick.

- Facebook, “Chase Community Giving on Facebook” (n.d.), https://apps.facebook.com/chasecommunitygiving/faq. See also T. Irwin, “American Express Reinstates ‘Members Project.’ ” Marketing Daily, March 8, 2010. Available at http://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/123849. And Pepsi, “Harvard Business Review Selects Pepsi Refresh Project as Marketing Case Study,” December 6, 2011. Available at http://www.pepsiamericas.com/Story/Harvard-Business-Review-selects-Pepsi-Refresh-Project-as-marketing-case-study12062011.html.

- S. Gregory, “Behind Pepsi’s Choice to Skip This Year’s Super Bowl,” Time, February 3, 2010. http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1958400,00.html.

- Some participants may even have resorted to cheating by paying proxy companies to artificially inflate their vote tallies. N. Zmuda, “Pepsi Refresh Project Faces Cheating Allegations,” Advertising Age, January 6, 2011, http://adage.com/article/news/pepsi-refresh-project-faces-cheating-allegations/148042.

- Wikipedia, “Wikipedia” (n.d.), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia.

- BBC News, “Wikipedia Survives Research Test,” December 15, 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4530930.stm.

- For the Britannica response, see Encyclopædia Britannica, “Fatally Flawed: Refuting the Recent Study on Encyclopedic Accuracy by the Journal Nature,” March 2006, http://corporate.britannica.com/britannica_nature_response.pdf. For Nature’s rebuttal, see Nature, “Encyclopædia Britannica Advertisement Response” (n.d.), http://www.nature.com/nature/britannica/eb_advert_response_final.pdf.

- Wikipedia, “Wikipedia” (n.d.), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia.

- N. Cohen, “Wikipedia to Limit Changes to Articles on People,” New York Times, August 24, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/25/technology/internet/25wikipedia.html; see also Wikipedia, “Wikipedia: Administrators” (n.d.), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Administrators.

- Wikipedia, “Wikipedia: Bureaucrats” (n.d.), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Bureaucrats; and Wikipedia, “Wikipedia: Arbitration Committee” (n.d.), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Arbitration_Committee.

- For details about the site’s reputation system, see Stack Overflow, “Frequently Asked Questions” (n.d.), http://stackoverflow.com/faq. For the current number of users, see Stack Exchange, untitled (n.d.), http://stackexchange.com/leagues/1/week/stackoverflow.

- It is true that the digital divide is a pressing cultural equity issue that would affect the representativeness of participation on a platform like the Gate in the short term. The authors feel that there are many incentives for government and business to ensure near-universal access to the Internet in the next ten to twenty years, and are therefore optimistic that the digital divide will become less important over time. In the interim, measures to support artists in rural areas or in extremely poor communities might be best pursued outside this platform.