Artist-Centered Grantmaking & Lives of Artists

How knowledge of artists’ internal development can benefit artists and the field that serves them, Part I

This is the first part of a two-part series on individual artist support written by Marc Zegans and published by GIA. Following-up to his GIA Reader article from 2017, Zegans offers his perspective on the cycle of creative growth that artists experience throughout their careers, and opportunities for grantmakers to re-examine how they develop and adjust their practices to meet nonlinear needs. “To be optimally effective, artist-centered grantmaking must capably support both incremental creative development and periods of metamorphic change,” Zegans writes. In this first installment, Zegans characterizes the creative life of artists and their internal development.

Read part two, focusing on implication for practice.

In 2017, I wrote an article for the GIA Reader called, “Arc and Interruption: The Five Stages of the Creative Life and the Crises that Intervene.” That piece presented a path model of a fulfilled creative life that I had developed inductively following years of working closely with artists, listening to their stories, and seeing them through their struggles. This model characterized the fulfilled creative life as a punctuated process involving alternating phases of cumulative development and periods of sharp, disjunctive change.

The notion of creative development as a punctuated process contrasts sharply with the conventional Emerging-Mid-Career-Established Artist (E‑MC‑E) model that treats artistic development as both incremental and measurable by easily quantified markers of productivity — such as exhibitions, grants, residencies, awards, teaching positions, press, and the like.

The distinction between seeing creative life as a punctuated path and as continuous incremental progress is important because the latter view, as expressed in the E‑MC‑E model, presumes that internal creative development and productivity are tightly linked over the course of an artist’s career. The punctuated path model does not. Rather, the punctuated path model says that creative development alternates between intervals of incremental growth and periods of metamorphic change, the latter occurring when the possibilities for further growth within a given stage of internal development are exhausted.

Visually, we can represent the punctuated path concept’s more nuanced perspective by charting the alternating states of fulfilled creative lives in relation to field building activities and direct artistic support.

TABLE 1. The Punctuated Paths of Fulfilled Creative Lives In Relation to Grantmaking

| Field Building | Artist Support | |

|---|---|---|

| Incremental Progression | ||

| Metamorphic Change |

Each cell in the “Incremental Progression” row is concerned with opportunities for grantmaking closely tailored to the stable periods of an artist’s internal development. Each cell in the “Metamorphic Change” row offers analogous opportunities for grantmaking keyed to the critical transitions that intervene between stable phases of an artist’s career.

The fundamental implication of this model is clear. To be optimally effective, artist-centered grantmaking must capably support both incremental creative development and periods of metamorphic change. The need for such support is not trivial. Though self-reliant, adaptive, and resourceful, artists struggle, stagnate, and drop out because they lack grounded insight into how creative lives unfold. And, they urgently need — and largely lack access to — situationally appropriate support and counsel. This argues for designing and implementing interventions geared to the internal developmental processes that artists follow, rather than to external markers of past productivity.

Such artist-centered, developmentally focused interventions would deliver results far different than simple business skills. Collectively, they would foster creative growth and consequent cultural contribution throughout artists’ lives.

The punctuated path model of creative development I introduced in “Arc and Interruption” points to what these interventions might be concretely. In what follows I summarize the model, then describe some of its more promising implications for field building and artist support.

Elements of the Model

The model of punctuated creative development looks at a fulfilled creative life as a recurring cycle of growth and as the developmental path within which such cycles occur.

Cycle of Growth

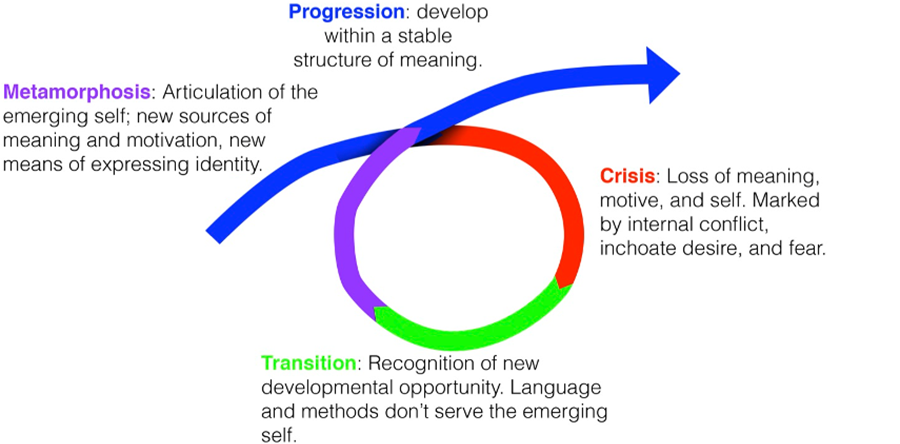

Creative lives are organized by the interplay of expressive desire and proximate developmental challenge. The interchange and periodic conflict between the two yield a four-part cycle of growth: progression, crisis, transition, and metamorphosis. (Figure 1) Let’s look at each phase in turn:

© Marc Zegans 2017. All rights reserved

Progression – Cumulative development within a stable structure of meaning.

When an artist’s primary developmental challenge and expressive desires are aligned, the artist’s structure of meaning is stable, and proficiency develops cumulatively. Such an interval constitutes a stage of routine progression.

Crisis – Loss of meaning, motive, and sense of self, marked by internal conflict, inchoate desire, and palpable fear.

Creative crises emerge when an artist’s worldview provides guidance inadequate to that artist’s needs. To resolve the crisis, an artist must cultivate an expanded self-concept and a structure of meaning adequate to the full scope of that artist’s expressive and developmental needs.

Transition – Perception of new developmental opportunity accompanied by the recognition that habitual language and methods do not serve the emerging self.

In contrast to creative crisis — characterized by loss, uncertainty, internal conflict, and fear — the transitional phase is marked by a decisive clarity. Its sharpness arises from the artist’s acknowledgment that the old language and methods no longer serve. Artists in transition begin to envision the self they can be and start to craft that identity accordingly.

Metamorphosis – Full articulation of the new self, one that embodies novel sources of meaning and motivation, expressive language, structural metaphors, and creative methods.

During metamorphosis artists conceive and embrace novel vision, fresh language, and new methods. Metamorphosis is complete when the artist has expressive resources sufficient to enter a new stage of progression.

Holding a picture of these cycles clearly in mind, let’s turn to the arc of the creative lives within which these recurring cycles of growth unfold.

Developmental Path

The punctuated path of a fulfilled creative life follows time’s arrow: It points forward. This path’s trajectory is determined by an alternating series of developmental tasks and existential questions, the former breeding long stages of incremental growth, the latter precipitating the sequence of crisis, transition, and metamorphosis, that, if completed, ready the artist to proceed with the developmental task that defines the next stage of their progression.

Forward progress is not a given. An artist can refuse the task at hand; abandon their practice; stagnate or perpetuate ambivalence via inconsistent and self-destructive behavior. Nor is it necessary for an artist to travel the full arc described by this model to lead a fulfilled creative life. An artist can find enduring satisfaction at mid-points along the way.

This said, many creative lives would journey further and produce better work if artists commonly understood the developmental tasks and existential questions that lie along the way, and if they were afforded support coherently linked to these challenges and opportunities. Making widely known the factors that determine the arc of fulfilled creative lives can markedly reduce the likelihood that artists will stagnate or drop out.

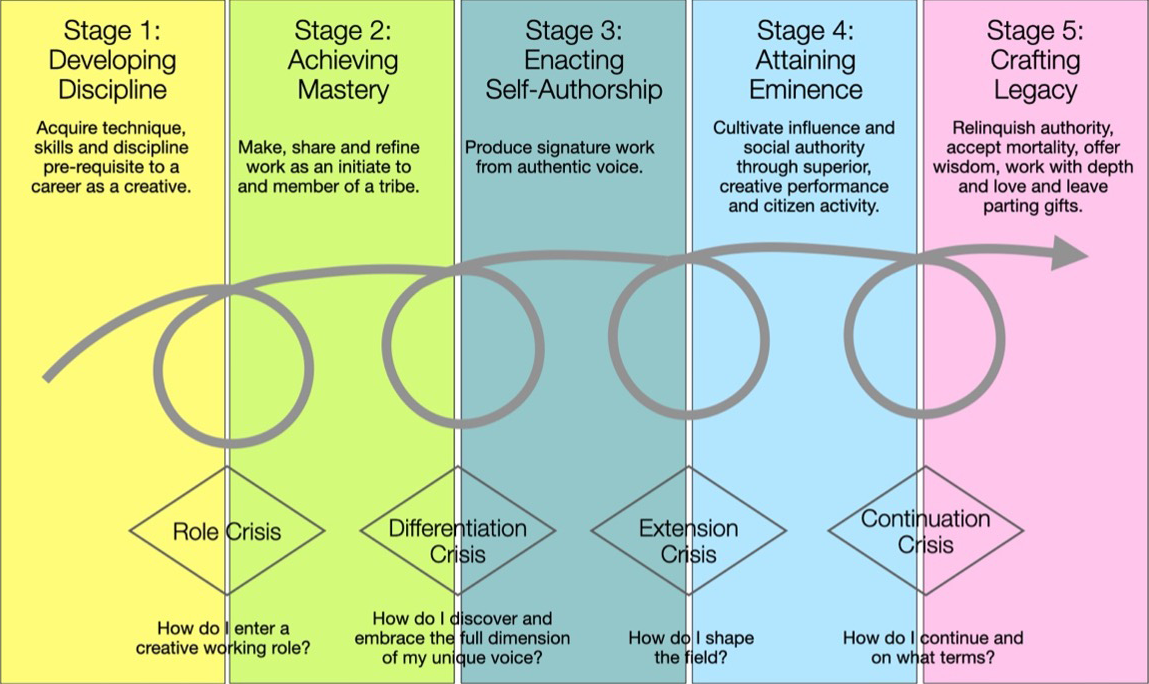

Let’s examine them. An artist’s internal development has five stages — [1] developing discipline, [2] achieving mastery, [3] enacting self-authorship, [4] attaining eminence, and [5] creating legacy — and four intervening disruptions — [1] role crisis, [2] differentiation crises, [3] extension crisis, and [4] continuation crisis. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2: The Arc of a Fulfilled Creative Life: The Punctuated Path of Creative Development

© Marc Zegans 2017. All rights reserved

Stage 1

Developing Discipline is the period during which an artist consciously develops craft. The central task is to acquire the skills needed to form bodies of work that fulfill their own intentions.

Intervening disruption: Role Crisis

The transition from artistic apprenticeship to working artist demands an expanded definition of self. Typically, new artists are neither emotionally nor conceptually prepared to meet this demand. To proceed a neophyte must adopt the social role of a working artist, accept the responsibilities that such a role entails, and chart a forward course.

Stage 2

Achieving Mastery is the process of becoming a capable working artist. This entails creating the capacity to make original work of increasing depth, proficiency, and meaning outside the scaffolded environment of the art school and cultivating the social skills needed to operate effectively in the art world.

Intervening disruption: Differentiation Crisis

Many artists find group membership to be a fulfilling calling; others feel an imperative to move beyond being one artist among many and become authors of their creative lives. Such artists often find themselves torn between the call to do their “real” work and the experience of safety in numbers. Artists advance to genuine self-authorship only when they compellingly answer the question, “How do I define, embrace, and stand up for my truest work?”

Stage 3

Enacting Self-Authorship is the practice of working from inner voice rather than estimates of the field’s requirements. Self-authoring artists follow the fierce volition to write their own life-script and to produce work that can be the product of no other.

Intervening disruption: Extension Crisis

After years of creating signature work some accomplished artists feel called to work on and for the field, rather than continuing to prioritize primary practice. Often, they experience this urge as a betrayal of the self-authorizing identity they recently fought to achieve. They must then ask, “Do I want to enter citizen-service or continue to be exclusively defined by my signature work?”

Stage 4

Attaining Eminence means assuming and constructively using social authority. Eminent artists shape the field and foster its development via superior creative performance because their work now speaks not only for themselves, but to and for the field, and through consequential activity on its behalf; they embrace the leader’s concern with who we are and where we must go.

Intervening disruption: Continuation Crisis

Lifelong artists eventually face the disquieting question, “How do I continue and on what terms?” Artists who thrive in late life answer this question by recognizing the freedom bestowed by great age, assuming the role of loving elder, and setting out to master the art of crafting legacy.

Stage 5

Crafting Legacy is the art of gracefully relinquishing authority, creating with depth and love, and leaving final gifts. An artist crafting legacy works intentionally, accepts what comes, offers sage advice, produces that which is needed, and is informed but never governed by accumulated experience.

The Arc of a Fulfilled Creative Life/Punctuated Path of Creative Development model suggests myriad possibilities for advancing best practice in artist-centered grantmaking, most significantly, by providing a paradigm for appropriately supporting artists at creative crossroads. In the second part of this piece, I will share implications for practice, how grantmakers can support artists through this paradigm, and possibilities for field building considering all these elements.

Acknowledgements

My deepest thanks to Linda Aldrich, Dudley Cocke, Nadia Elokdah, Prudy Kohler, Deborah Oster Pannell, Frances Phillips, Noah James Saunders, Andrea Saveri, and Jason Weeks for their support, encouragement, and sage counsel in bringing this article to fruition.

Marc Zegans is a creative development advisor who helps artists, writers, creative people, and arts organizations thrive and shine. A working poet, Marc is the author of six collections of poems. Films based on his poems have appeared at festivals around the world. He previously served as executive and research director of Harvard University’s Innovations in American Government Program. To learn more about Marc’s work, go to https://mycreativedevelopment.com.