Toward a History (and Future) of the Artist Statement

Google artist statement, and you will find a good dozen instructional websites enjoining artists to “follow these easy steps” to produce this essential bit of art-career ephemera. Most begin with a reassuring acknowledgment of artists’ presumed anxiety about putting visual expression into words, then launch into an encouraging pitch for the twofold fulfillment that awaits the obliging statement writer: not only will you be able to communicate clearly and effectively in the native language of the curators, critics, and collectors on whom your future depends, you will also discover — somewhere in the fresh transcription of your work — aspects of your creative essence that you never even knew existed. One “Master Certified Coach” provides the following appetizing advice: “Think of your artist’s statement as a nourishing stew. The rich flavors and inviting aroma will feed your spirit and summon wonderful people to your table.”1

The authors of Art/Work: Everything You Need to Know (and Do) As You Pursue Your Art Career devote an entire section to the task. In one page max (on brevity all the experts agree), “you just want to describe, as simply as possible, what it is that you hope to do, or show, or say, with your art, and what it is that makes you interested in doing, showing, or saying that.” If only it were that simple, for along with the dos comes a series of foreboding don’ts. Don’t posit “a comprehensive theory of your place in art history”; don’t “psychoanalyz[e] your motivation”; don’t use jargon; and above all, don’t fall prey to any among a list of phrases that “plague artist statements” with insincerity or obviousness, among them: “I pour my soul into each piece” and “My work is about my experiences.”2

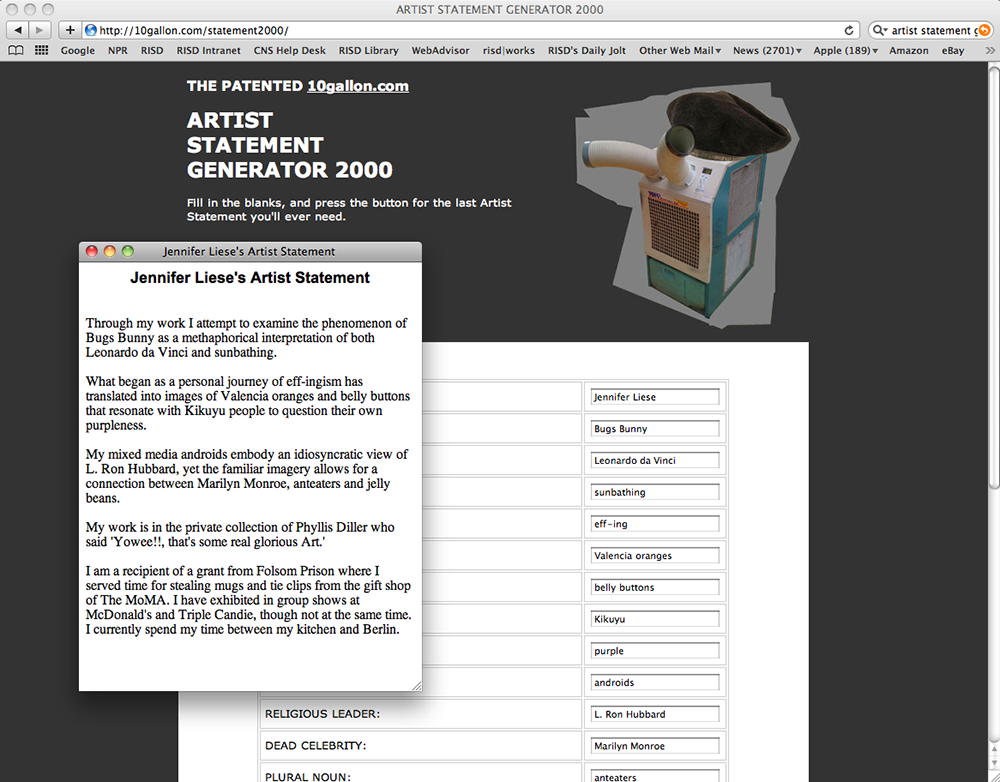

The artist Nick Fortunato has capitalized on the prevalence of such dubious guides and clichés with his “Artist Statement Generator 2000,” an online project launched in 2010 that asks the visitor to “Fill in the blanks and press the button for the last Artist Statement you’ll ever need.”3 Participants respond to prompts like “cartoon character,” “famous artist,” “verb ending in ing,” “plural food,” and “favorite museum.” A click on “create statement” produces a five-paragraph, Mad Libs–style gag in which the chosen words complete the template, yielding such absurd constructions as “Through my work I attempt to examine the phenomenon of Bugs Bunny as a metaphorical interpretation of both Leonardo da Vinci and sunbathing.” The final line hits its target of art-world affectation dead on. With all words preset other than the user-chosen “place in your home,” mine read: “I spend my time between my kitchen and Berlin.”

Screen grab from the author’s iteration of Nick Fortunato’s “Artist Statement Generator 2000.” Click/tap to enlarge

Of course, artists’ words have long been met with skepticism, not least by artists themselves. Matisse, despite his own eloquence, famously declared that “a painter ought to have his tongue cut out.”4 Pollock played dumb. Warhol mastered obfuscation. We know all of that. But artists’ writings are also much anthologized and well loved — for both their historical and literary value. (Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings and MIT Press’s Writing Art series are two standouts among many excellent collections.5) Following a relative dearth of published artist writings in the object-centered 1980s and 1990s, the past decade or so has seen a wave of them still too new to be anthologized — the distribution theories of Seth Price, the fictional narrative as impetus for art of Mai-Thu Perret, and the semi–art historical situating of Josiah McElheny, to name a few. Such diversely inclined artist-writers are keeping the form very much alive.

Still, there’s no denying the sorry state of the statement, and we all know it. The ubiquitous request “Please include an artist statement . . .” inspires cringes and groans among artists. An artist friend of mine called artist statements “the dentistry of the art world,” and Fortunato is not alone in making art that mocks the form; one of several statement satires on YouTube features a pair of animated pig-artists translating pretentious claims of artist statements into the banal truth. Likewise, art professionals are tired of reading these often hyperbolic, embarrassing, or at best monotonous texts. Artist Nina Katchadourian, former curator of the Drawing Center’s Viewing Program, once told me that of the hundreds of artist statements she had read that year, only one really stood out.6 A gallery owner interviewed in Art/Work emphatically states that he never reads artist statements.7 What could be more deflating? You slave all week over your nourishing stew and no one even bothers to taste it.

But who or what, we might ask, is to blame for this compositional rut? And once we’ve parsed causes, might we find some way to effect change, to liberate the artist statement for the good of us all? Taking history as a guide, maybe we could first learn a thing or two from the artist statement’s past. Where did this ever-present, compulsory overture come from anyway? Strangely, given its proliferation, the actual history of the genre remains a mystery. No one seems to have written a book on the subject, or even a dissertation.8 Any practical and theoretical discussions of artist statements that do exist leave their history untold, perhaps because the form’s exact criteria remain undefined.

Anthologies of artist writings — which include letters, manifestos, journals, criticism, and interviews along with statements — are organized by chronology, theme, or country, rather than type. The editors’ introductory essays make surprisingly few distinctions among various forms of artists’ writings. Further complicating the matter is the fact that the term “statement” is so readily generic. Sometimes it is applied to writings that were originally presented as lectures or pieced together from interviews. Picasso’s “Statements,” for example, were in several instances constructed from conversations with trusted confidants.9 By contrast, Claes Oldenburg’s celebrated “I Am for an Art” (“I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.”), printed first in 1961 and reprinted many times thereafter, is usually referred to as an essay or a manifesto, though it is titled “statement” on an early typed manuscript.10

Robert Goldwater, coeditor of the 1945 anthology Artists on Art: From the XIV to the XX Century, provides in his introduction a handy and ultimately telling century-by-century characterization of broad trends among artists’ writings. The 14th and 15th centuries, he notes, were dominated by handbooks on technique such as Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’Arte, which advises artists on painterly matters ranging from how to depict drapery in fresco to preserving a steady hand by drinking only thin wines. Artists in the 16th and 17th centuries tended toward the theoretical, as in Michelangelo’s rigorous efforts to rank the arts hierarchically, a popular undertaking at the time. The 18th century brought both an uptick in academic discourse and a surge in journals such as Delacroix’s. The 19th century was characterized by private letters such as van Gogh’s and the early 20th century by the public manifesto. Regarding the mid-20th century, on the cusp of which this anthology was published, Goldwater issues the following prediction: “If introspection is losing ground, the public statement appears to be gaining.”11 While this mention doesn’t locate a birth of the artist statement, it does allude to its breakthrough moment.

In “Network: The Art World Described as a System” — Lawrence Alloway’s still-potent 1972 critique of an art “regime” that produces not art but rather “the distribution of art, both literally and in mediated form as text and reproduction” — the critic notes that the artist statement was the “typical verbal form of the Abstract Expressionist generation.” Indeed, there were many outlets for the statement at midcentury: art magazines such as As Is, The Tiger’s Eye, and Possibilities printed them verbatim. Alloway describes the artist statement as “essentially a first person expression putting succinctly fundamental ideas about art.”12 That much is a start in defining terms. But wouldn’t many other forms of artists’ writings meet the same criteria? The interview, for example, is rendered in first-person and might well include fundamental ideas about art. But of course the interview generally originates with the spoken rather than written word and involves an influential interlocutor.13 Artists’ journals and letters both fit Alloway’s description, but they initially have only an audience of oneself or one other in mind. The manifesto might be written by a single artist, but, as Mary Ann Caws points out in her introduction to Manifesto: A Century of Isms, this archetypal form uses “we-speak” as a persuasive tactic in converting others to a collective cause — “We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness,” begins Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto — while the artist statement serves primarily to elucidate the artist’s own work.14

How then might we refine Alloway’s definition? A proposal: The artist statement is “a first-person [written] expression [intended for readership,] putting succinctly fundamental ideas about [one’s own] art”? I would propose adding still another, more contemporary criterion to this stab at typology: the artist statement, as we know it today, is produced to meet an explicitly professional occasional need, such as accompanying the artist’s work in a magazine, exhibition catalogue, grant application, or on the artist’s website. Looking back at some of the most exceptional artist statements of the 20th century, we find many that hew perfectly to this definition, and even shade into blatant self-promotion, without — it should be noted — “sounding like an artist’s statement.”15

In 1908, for example, Matisse wrote what art historian Jack Flam calls “one of the most important and influential artist’s statements of the century.” “Notes of a Painter,” the artist’s first published text, was solicited for the French literary journal La Grande Revue. Clocking in at some three thousand words, it addresses color, composition, painting from nature versus painting from imagination, and fellow artists, and it includes one of those art adviser’s verboten “comprehensive theories” — on artists’ inability to escape their moment in history: “All artists bear the imprint of their time,” Matisse writes, “however insistently we call ourselves exiles from it.” Far-reaching and provocative, the statement is nonetheless transparently careerist. As Flam points out, one of Matisse’s intentions was to “clear himself of some of the criticism leveled against him in both reactionary and avant-garde circles,” and indeed the painter calls out his critics by name. Another intriguing bit of self-promotion — direct marketing you might call it — is hidden just beneath the surface, right there in the statement’s best-known line: “What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, an art that could be for . . . the businessman as well as the man of letters, for example, a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair that provides relaxation from fatigue.” This line, which would long after reinforce critiques of Matisse’s work as merely decorative, was, Flam argues, directed to one particular “businessman” — Sergei Shchukin, a Russian collector and Matisse’s new patron, who had told Matisse that his paintings offered him consolation amid personal tragedy.16 Hence Matisse’s shameless plug for the armchair effect, right in the middle of one of the most important artist statements of all time.

American art magazines weren’t far behind the French in publishing artist statements. Marsden Hartley’s, for example, “Art — and the Personal Life,” appeared in Creative Art in 1928. A paradoxically passionate defense of the artist as a thinking rather than wholly feeling being, the text begins: “I have joined, once and for all, the ranks of the intellectual experimentalists. . . . Personal art is for me a matter of spiritual indelicacy.” What takes the place of “expressionism” and “emotionalism” in Hartley’s construct? “I am interested in the problem of painting, of how to make a better painting according to certain laws. . . . It is better to have two colors in right relation to each other than to have a vast confusion of emotional exuberance in the guise of ecstatic fullness or poetical revelation.”17 Hartley’s steadfast rationality is radical, defying what Brian Wallis would one day call “one of the most enduring and telling fantasies of modernist culture” — that the artist is a feeling, inarticulate genius.18 Marcel Duchamp recognized this myth — and its consequences — when, in a 1957 lecture, he described the pigeonholing of the artist as a “mediumistic being” who is denied “the state of consciousness on the esthetic plane about what he is doing or why he is doing it.”19 In other words, Hartley’s statement is an object lesson in refusing to play the sensitive mute.

In 1954 Louise Bourgeois wrote a statement, published in Design Quarterly, that is otherwise a straightforward description of her work, but which begins with a caveat worth quoting at length for its insight into the essential challenges of writing about one’s own art:

An artist’s words are always to be taken cautiously. The finished work is often a stranger to, and sometimes very much at odds with what the artist felt, or wished to express when he began. At best the artist does what he can rather than what he wants to do. After the battle is over and the damage faced up to, the result may be surprisingly dull — but sometimes it is surprisingly interesting. The mountain brought forth a mouse, but the bee will create a miracle of beauty and order. Asked to enlighten us on their creative process, both would be embarrassed, and probably uninterested. The artist who discusses the so-called meaning of his work is usually describing a literary side-issue. The core of his original impulse is to be found, if at all, in the work itself.20

Surveying artist statements from throughout the 20th century, it’s remarkable to see how many begin similarly — disavowing the task at hand before undertaking it, as if to offer some protection or cathartic release. Matisse’s “Notes of a Painter” makes the same point in a sentence: “I am fully aware that a painter’s best spokesman is his work.”21 Alexander Calder writes, “Theories may be all very well for the artist himself, but they shouldn’t be broadcast to other people.”22 Robert Rauschenberg takes a subversive route, injecting bits of nonsense into his “Note on Painting”: “I find it nearly impossible free ice to write about Jeepaxle my work. The concept I planetarium struggle to deal with ketchup is opposed to the logical community life tab inherent in language horses and communication. . . . It is extremely important that art be unjustifiable.”23

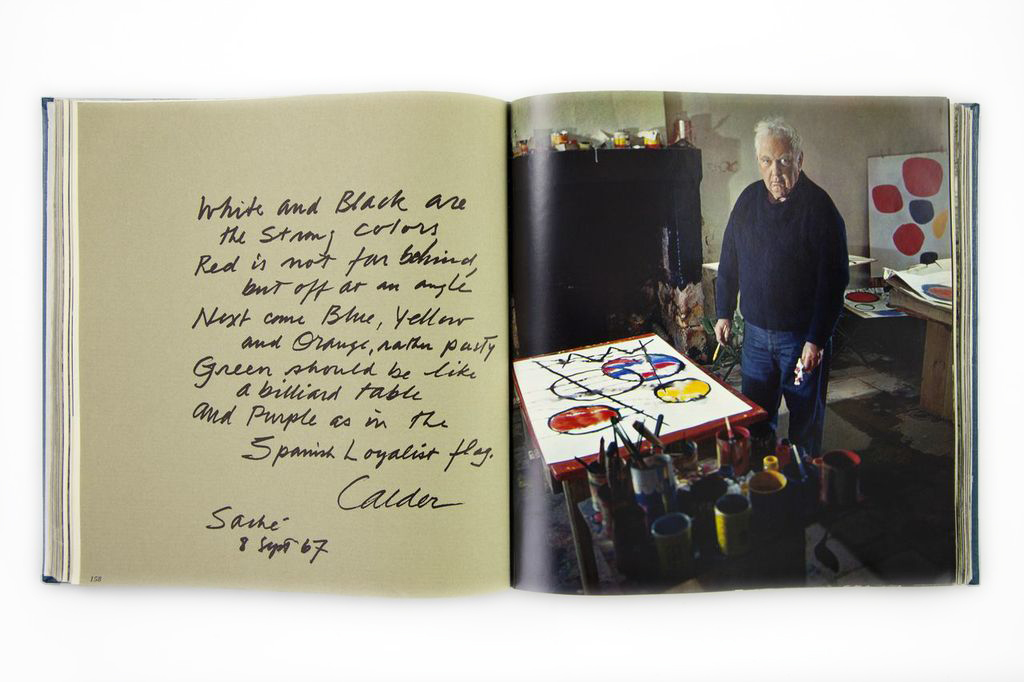

Spread from Daniel Frasnay, The Artist’s World (1969); Alexander Calder statement and portrait. Click/tap to enlarge

In the 1960s, in response to increasing popular interest in art, there appeared several photographic portrait books that sought to reveal truths about artists’ works and personae through views into their studios. Alexander Liberman’s The Artist in His Studio (1960) is perhaps best known among them, but The Artist’s World, published in 1969, with photographic collages by Daniel Frasnay portraying some fifty artists, offers another layer of insight through its accompanying statements. Wildly divergent, most appear to have been written for the occasion, and many appear in the artist’s own script. Some are technical. Sonia Delaunay, for example, offers the following equation of her color theory:

Others are playful. Here is Calder’s treatment of color:

the strong colors

Red is not far behind,

but off at an angle

Next come Blue, Yellow

and Orange, rather pasty

Green should be like

a billiard table

and Purple as in the

Spanish Loyalist flag.

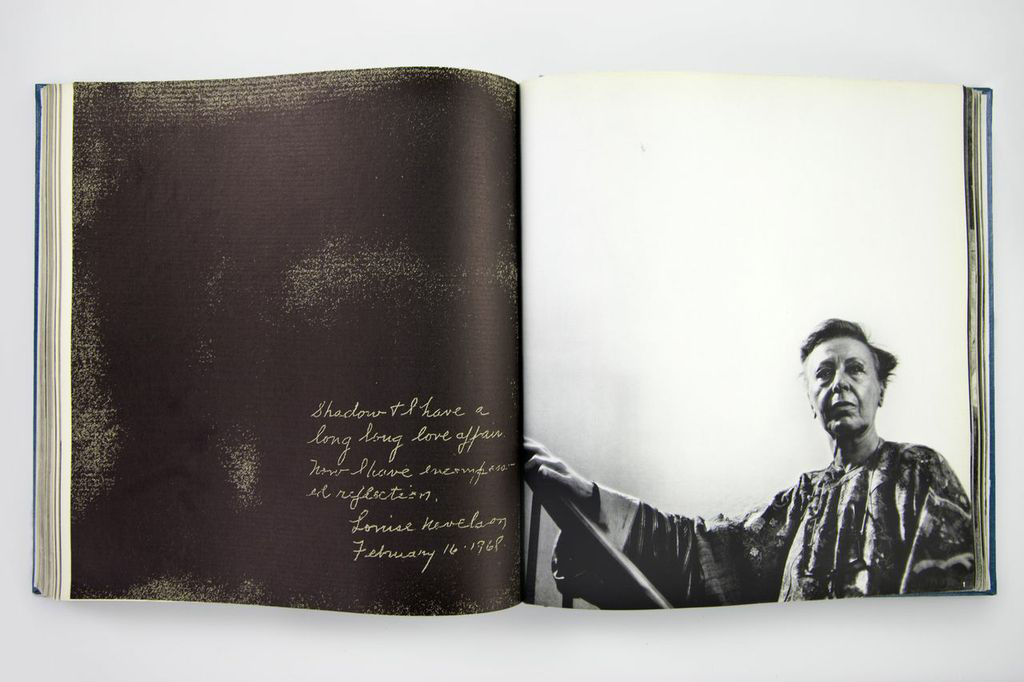

Spread from Daniel Frasnay, The Artist’s World (1969); Louise Nevelson statement and portrait. Click/tap to enlarge

Some are romantic: “Shadow & I have a long long love affair,” writes Louise Nevelson. Others evanescent: “I grope in space for the vibrating invisible white thread of the magical that lets fall facts and fancies like the music of a stream singing its way through pebbles, quick and precious,” effuses Giacometti. Some are self-doubting, like Adolph Gottlieb’s: “Surrounded by my materials, canvas, paints, oils, brushes, etc. I feel like a relic of the past because paintings are still among the few things made by hand.” Others process-oriented, as with Karel Appel: “I make myself free, I stand aside, I squeeze myself dry. Then I am ready to begin painting.” Some are droll: “Rembrandt is beautiful, but sad. Boucher is gay but bad. ‘Great Painting’ has never made anyone laugh,” observes Jean Dubuffet. And at least one, Roberto Matta’s, is exhilaratingly exhortatory: “You have to stir up that subversive imagination that shatters the accepted formulas and ideas we’re imbued with and unleashes the poetic states. That exists in all of us and propels us toward the unforeseeable. YOU’VE JUST GOT TO GET TO THAT INNERMOST CORE!”24

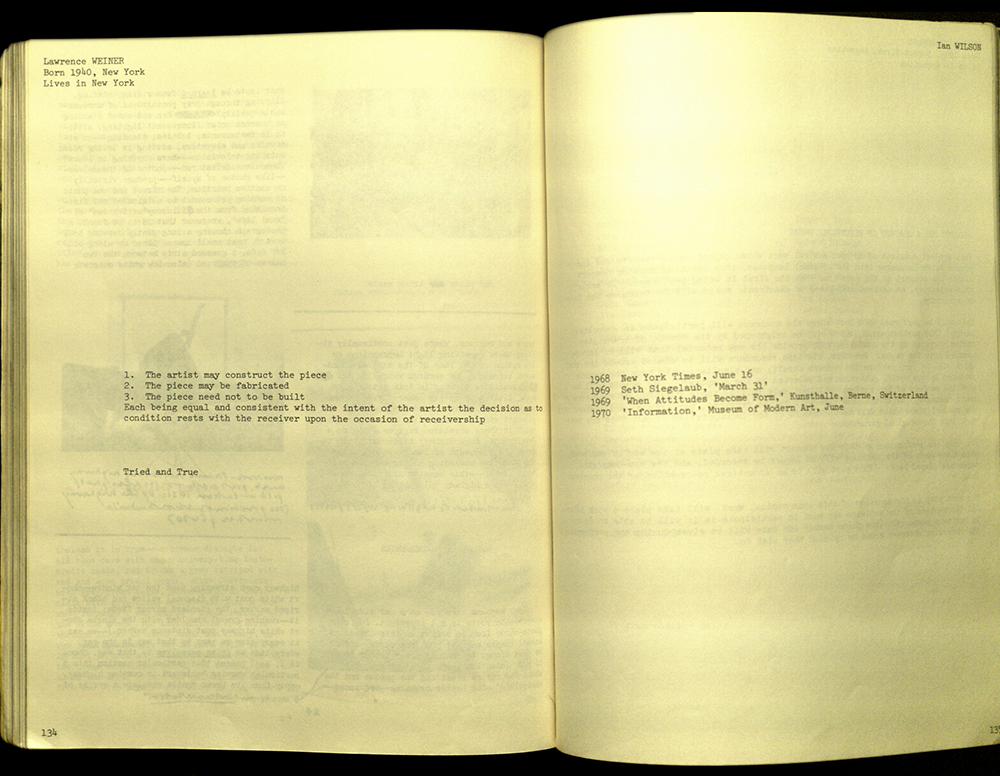

By the 1970s and 80s, the primary site of published artist statements seems to be the exhibition catalogue. Lawrence Weiner’s famous “Untitled Statement,” the one that goes:

- The artist may construct the piece

- The piece may be fabricated

- The piece need not be built

appeared in the catalogue for the influential 1970 MoMA show Information.25 Eva Hesse, a year before she died, wrote a catalogue statement of loose, deeply intimate notations that move back and forth with painful ease between art and illness. It begins:

Rubberized, loose, open cloth.

Fiberglass — reinforced plastic.

Began somewhere in November-December, 1968.

Worked.

Collapsed April 6, 1969. I have been very ill.

Statement.

And after a half-dozen more such stark counterpoints, it ends:

Ed Ruscha in a statement for 50 West Coast Artists (1981), covers concrete topics from his biography (born in Omaha) to his influences (“The painting of a target by Jasper Johns was an atomic bomb in my training”), yet also includes a resolute claim for ambiguity: “I am committed to collecting thoughts and potential issues. The result can be vague if it wants to be. It’s not important. The important thing is to create a sort of itch-in-the-scalp.”27 Magdalena Abakanowicz, in a statement published in an exhibition catalogue around the same time, is contrastingly razor-sharp: “I wanted to tell you that art is the most harmless activity of mankind. But I suddenly recalled that art was often used for propaganda purposes by totalitarian systems. I wanted to tell you also about the extraordinary sensitivity of an artist, but I recalled that Hitler was a painter and Stalin used to write sonnets.”28 Gilbert & George, whose self-published booklets of the early 1970s — A Guide to Singing Sculpture; A Day in the Life of George & Gilbert the Sculptors; The Pencil on Paper Descriptive Works of Gilbert & George the Sculptors (a single three-page-long sentence) — were essential early iterations of their work. They state the case for unconventional artist statements straightaway in their 1978 statement:

Life of the Artist who is an eccentric person

with something to say for Himself.29

In 1989, Mike Kelley wrote “Statement for Prospect 89” for a catalogue for the German exhibition of the same name. Here is a bit of its climactic, and now haunting, prose: “Wallflowers . . . those shy ones! Oh! Cling! Cling thee to the furthermost borders — the hinterlands. Sublimate, oh, sublimate thy libidinal impulses into decorative organic motifs . . . ornamental hair growths, aesthetically placed tattoos. Beauty-mark thyself! . . . Oh! Oh! Oh!”30 In the preface to his collected “functional” writings, Kelley surmises that he has earned his right to this sort of utter absurdity: “I suppose that I have been in the art world long enough to feel some sense of security that an adopted ‘crackpot’ voice will not necessarily be confused with my own; or I just don’t care anymore if it is. ”31

Of course it’s artists less established than Kelley who are more likely to be asked for an artist statement at all, and they probably do care very much if someone thinks they are crackpots. Nowadays, the statement isn’t typically meant for publication in an avant-garde magazine or a career-defining catalogue. The occasions are more frequent and mundane: professors require them as supplements to critiques; grant givers, residency programs, and grad schools request them as support material; galleries solicit them as fodder for press releases; or you just need “something for a website.”32 An artist statement is supposed to fulfill overlapping and shifting professional requirements, while at the same time managing to sound like an uncoerced statement of principles. The regularity and inherent conflict in these requests are confusing, and the combination of strict guidelines and obscure goals is the real-life “artist statement generator” that produces so much turgid and overreaching prose.

I am the director of the Writing Center at Rhode Island School of Design, where a group of peer tutors and I work with student writers on all kinds of writing, including our share of tortured artist statements. In the process, I think we’re starting to learn something about how to help young artists write effectively about their work. A couple of years ago, Arianne Gelardin, a RISD graduate student and Writing Center tutor, set up a workshop designed to help students prepare their artist statements for the RISD Grad Book 2011. For this catalogue, which she edited, Gelardin explicitly offered all statement writers “the agency of choice” — a chance to experiment, to diverge.

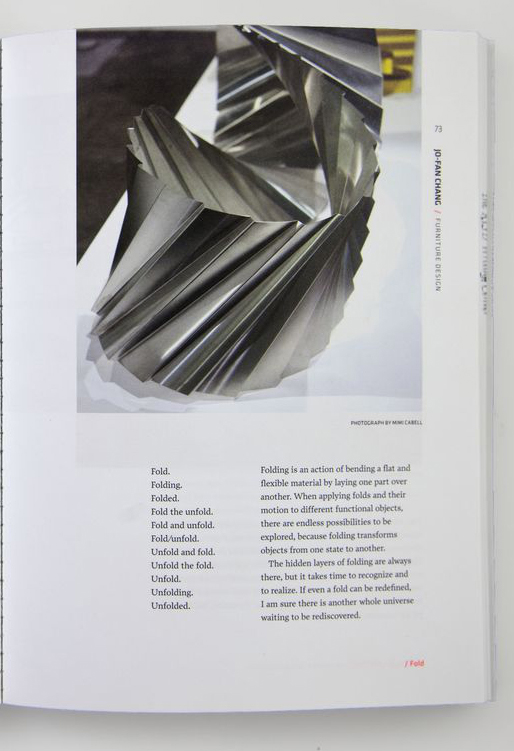

Some really took her lead. Here’s Lisa Jo-Fan Chang, layering concrete poetry onto the fanlike form of her furniture design:

Folding.

Folded.

Fold the unfold.

Fold and unfold.

Fold/unfold.

Unfold and fold.

Unfold the fold.

Unfold.

Unfolding.

Unfolded.

Here’s Mimi Cabell, a photographer, performance artist, and writer, standing her ground: “I do not apologize and I am not sympathetic. . . . I do not hear grays in people’s voices, only the blacks and the whites. I hear yes and no, here and there, on and off. Not maybe, or somewhere, or running at half speed.” And finally, here’s Byeongwon Ha, a new media artist, with a piercing reminiscence of life before such media:

Coaxing such apt, confident, and memorable writing out of artists, who aren’t all artist-writers after all, isn’t always so straightforward. The various parties that assign and request artist statements don’t always offer the same freedom that Arianne did. Explicitly or implicitly, they endorse the conventional wisdom, the codified model for fill-in-the-blank, forced prose meant to serve as the ultimate linguistic record of an artist’s work. It’s worth noting that according to many scholars in writing pedagogy, these factors — checklist writing prompts, prescribed outcomes, external rather than internal motivation, and one-shot attempts — prohibit expressive and effective writing. Writing is better practiced as an ongoing process in which a series of self-discoveries unfold in organically organized form.34

But what’s the alternative to our formulaic norm? Far from uncovering some definitive unstatement, the selective history of artist statements offered here shows them to be as varied and complex as the conditions that brought them forth. Comprehensibility, tastefulness, and brevity were clearly not always the goals. These statements, rather, are generous, adventurous, defensive, incisive, vindictive, eccentric, experimental, bombastic, sly, sad, funny, personal, political, and poetic. It’s hard to tell when they even began. Indeed, the difficulty of locating a precise “birth of the artist statement” is both explanatory and potentially liberating, since many of the genre’s most depressing examples seem to be written as if the writer is trying — and failing — to emulate some kind of “correct” model, one that he or she has never actually set eyes on. Artists have become convinced they’re supposed to say “my work explores the notion of self-reflexivity” rather than “I paint about paintings,” but they aren’t sure why. It’s like sitting down to write a poem and throwing in a bunch of thees and thous because that’s how poetry is supposed to sound. The results are obviously less than artful.

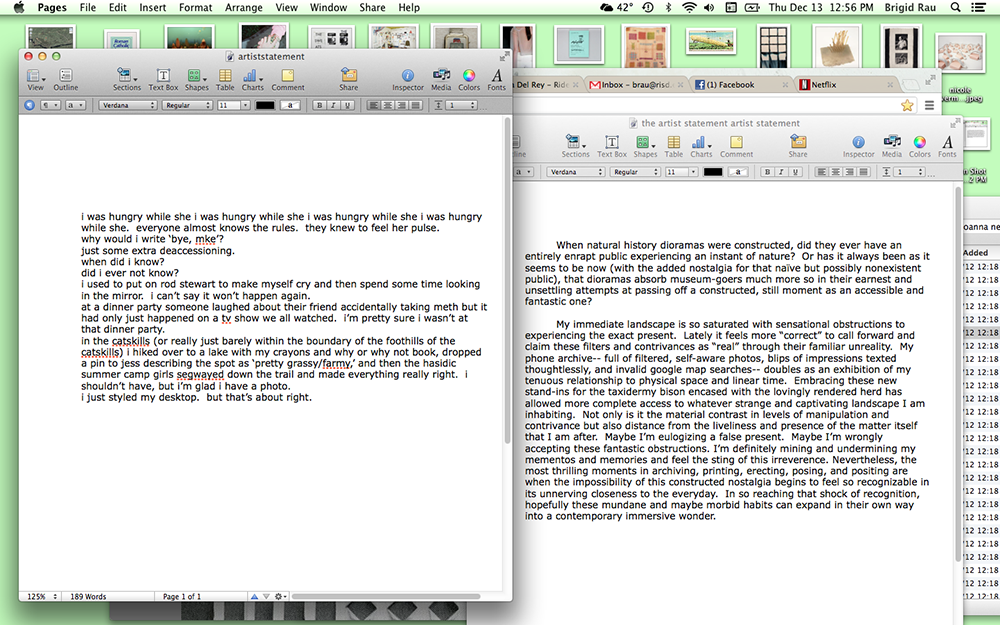

A couple of years ago I met the reliably contrarian critic Dave Hickey, who, on hearing that I work with art students on their writing, immediately announced: “The artist statement should be abolished!” It was a tempting solution, I must admit, but I wasn’t going to leave it there. “Why is that?” I asked. “Because artists don’t know what they’re doing,” he said. I almost took the bait, but thought twice and knew — I think anyway — just what he meant: if they know exactly what they’re doing, it’s not art. Precisely. But rather than abolish artist statements, why not adjust the current rules of the game? An artist statement can be an authentic, generative complement to the work, as I witnessed recently when Brigid Rau, a RISD senior who photographs images projected onto textiles — inextricable layers referencing our screen-based visual landscape — wrote an artist statement that layered multiple narratives on multiple screens, then captured it as a screen grab of her monitor. The one-size-fits-all explanatory imperative might seem like an efficient way to get artists to speak a language that everyone else — curators, collectors, professors, critics — can understand, but the overall result, let’s admit it, is usually a really horrible Esperanto. For everyone’s sake — artists and the people and institutions working to support them — it would be better to welcome sense and nonsense, coherence and paradox, philosophy, poetry, and maybe even a little more than a page, all of which might truly represent, rather than reduce, artists and their art.

- Molly Gordon, “How to Write and Use an Artist’s Statement,” www.mollygordon.com/resources/marketingresources/artstatemt/.

- Heather Darcy Bhandari and Jonathan Melber, Art/Work: Everything You Need to Know (and Do) as You Pursue Your Art Career, Free Press, 2009, pp. 68–70.

- 10gallon.com/statement2000.

- Jack Flam, ed., Matisse on Art, University of California Press, 1995, p. 2.

- See Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz, Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings, University of California Press, 1995. MIT’s Writing Art series includes collections of writings by more than twenty artists, among them Carl Andre, Dan Graham, Yvonne Rainer, Mike Kelley, and Andrea Fraser. Other anthologies of artist writings that informed this article include: Herschel B. Chipp, Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics; Robert Herbert, Modern Artists on Art: Ten Unabridged Essays; Ellen Johnson, American Artists on Art from 1940 to 1980; Dore Ashton, Twentieth-Century Artists on Art; Katherine Kuh, The Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Modern Artists; Eric Protter, Painters on Painting; Robert Goldwater and Marco Treves, eds., Artists on Art from the XIV to the XX Century; Brian Wallis, ed., Blasted Allegories: An Anthology of Writing by Contemporary Artists; Mary Ann Caws, Manifesto: A Century of Isms; and Jack Robertson, Twentieth Century Artists on Art: An Index to Artists’ Writings, Statements, and Interviews.

- In the exemplary statement, artist Kathleen Henderson juxtaposes a fantastical childhood memory with a traumatic news report she read many years later. Katchadourian noted, “The statement helped me clue in to the violence and rawness in her drawings, which are very important parts of them, and she did this in a much more interesting way than the tired formula of the artist statement that begins ‘I am interested in.’” Email to the author, November 7, 2012.

- Bhandari and Melber, p. 68.

- The only significant scholarly take on the artist statement I came across is an issue of the Canadian journal Open Letter (Fall 2007) devoted to “Artists’ Statements and the Nature of Artistic Inquiry.” Contributors consider the form from a variety of perspectives — in relation to rhetoric, poets’ statements, and musical influence, for example. But only one seeks to situate the statement historically: Open Letter editor Frank Davey provides a valuable analysis of the reception history of the artist statement in relation to Wimsatt and Beardsley’s “The Intentionality Fallacy” (1946); Roland Barthes’s “The Death of the Author” (1967); and Pierre Bourdieu’s The Rules of Art (1996).

- For example, the first-person running narrative published as “Picasso Speaks” in The Arts (May 1923) began as an interview with Marius De Zayas. Chipp, p. 263.

- Published first in the exhibition catalogue Environments, Situations, Spaces, Martha Jackson Gallery, 1961, a rough typed version of “I Am for an Art” headed “statement” is among the Ellen Hulda Johnson papers, Archives of American Art. Accessed online at www.aaa.si.edu/collections/images/detail/claes-oldenburg-artists-statement-environments-situations-spaces-catalog-7971.

- Goldwater and Treves, pp. 22, 23, 17.

- Lawrence Alloway, “Network: The Art World Described as a System,” Artforum, September 1972, pp. 29, 30.

- The Fall 2005 issue of Art Journal features a series of excellent articles on the artist interview.

- Caws, pp. 187.

- Given limitations of space and time, the examples that follow here — organized chronologically to suggest a rough sketch of the venues in which statements have appeared over time — are limited to published artist statements. One can imagine the thousands of statements that never made their way out of artists’ gallery files. Future research on the artist statement would include visits to the Archives of American Art or the Museum of Modern Art’s artists’ files. My thanks to MoMA archivist Jenni Tobias for a promising initial conversation about what one might find there.

- Flam, pp. 30, 43, 30, 42, 35.

- Reprinted in Chipp, pp. 526–9.

- Wallis, Frank Davey traces the dismissal of artists’ intellects back to Plato, who wrote of the poets in his Apology that “no wisdom enabled them to compose as they did, but natural genius and inspiration; like the diviners and those who chant oracles, who say many fine things but do not understand anything of what they say.” “Artists’ Statements and the ‘Rules of Art,’” Open Letter, Fall 2007, p. 35.

- Marcel Duchamp, “The Creative Act,” in The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, eds., Da Capo Press, 1973, p. 139.

- Originally published in Design Quarterly, no. 30 (1954), p. 18. Reprinted in Bourgeois, Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews 1923–1997, eds. Marie-Laure Bernadac and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, MIT Press, 1998, p. 66.

- Flam, p. 37.

- In Joann Prosyniuk, ed. Modern Arts Criticism: A Biographical and Critical Guide to Painters, Sculptors, Photographers, and Architects from the Beginning of the Modern Era to the Present, vol. 2, Gale Research Inc., 1991, p. 57.

- Stiles and Selz, pp. 321–2. Sculptor David Smith would have appreciated Rauschenberg’s sentiment. He once proposed: “I think we artists all understand English grammar, but we have our own language, and the very misuse of dictionary forms puts our meaning closer in context. I think we’re closer to Joyce, Genet and Beckett than to Webster.” Kuh, p. 8.

- Daniel Frasnay, The Artist’s World, JM Dent & Sons Limited, 1969, pp. 34, 158, 270, 204, 236, 288, 300, 260.

- Stiles and Selz, p. 839.

- Ibid., p. 595.

- Ed Ruscha, Leave Any Information at the Signal, MIT Press, 2004, pp. 9–11. Swedish artist Jan Svenungsson, in his vital essay “The Writing Artist,” argues convincingly, and quite in line with Ruscha, that “ambiguity is crucial to good artists’ writing.” See www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n2/svenungsson.html.

- Stiles and Selz, p. 260.

- Robert Violette and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, eds., The Words of Gilbert & George: Writings and Interviews (with Portraits of the Artists), 1968–1997, Violette Editions, 1997, p. 96. The editors note that this statement was “written for use in exhibition catalogues.”

- Mike Kelley, Minor Histories: Statements, Conversations, Proposals, ed. John C. Welchman, MIT Press, 2004, p. v.

- Ibid., pp. xii–xiii.

- Strange that the DIY opportunity of artists’ own websites does not seem to have yielded much experimentation with the artist statement. Likewise, video artist statements, which are cropping up on YouTube, typically show artists reading aloud from still-dull statements while standing in front of their work. Artist blogs, on the other hand — ephemeral, visual — may illuminate some possibilities for artist statements.

- Arianne Gelardin, ed., RISD Grad Book 2011, Rhode Island School of Design, 2011, pp. 19, 73, 69, 108.

- See freewriting pioneer Peter Elbow’s Writing Without Teachers and Everyone Can Write (both Oxford University Press, 1973; 2000); and artist Lynda Barry’s What It Is, Drawn & Quarterly, 2011.