Imaginary Needs and a Raucous Caucus

Creative Support for Creative Artists

In the late 1980s, several hundred people met twice at remote locations on two islands, one on the US East Coast and one on the West, to consider “the creative support of the creative artist.” Sponsored by the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA), the first conference was held in May 1986 at Montauk on the eastern tip of Long Island, New York, and the second in November 1988 on Orcas Island near the Canadian border in Washington State. Although I attended both, I am deeply grateful to have had sources with agile memories so I didn’t have to rely only on my own. (I name names at the end of the article.)

Imaginary needs?

The full title of the conference at Montauk was “Imaginary Needs: Creative Support for the Creative Artist.” The idea of “imaginary needs” confused many participants. One wrote in a commissioned letter, “I’m a little baffled by the title for this gathering, as the needs of creative artists don’t seem the least bit imaginary to me.” Though no explanation was given, Ella King Torrey, program officer at The Pew Charitable Trusts, offered her interpretation: “Artists were increasingly left out of the conceptual as well as the economic picture… Was that because we didn’t need to notice? Were the needs of artists imaginary? What really were the needs of the imagination?”

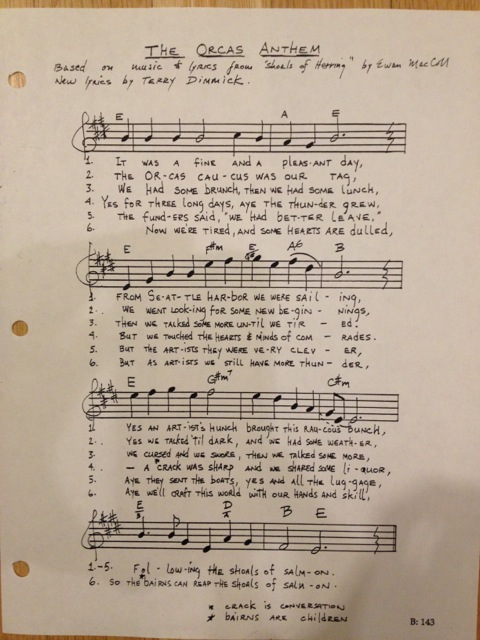

The two conferences shared similar goals. As summarized in a report by writer/editor Becky Lewis, the Montauk conference was designed to give participating artists and others a chance to “think about and discuss the role of the artist and the systems that support the creation of art in our society… to question, compare notes, testify, and wrestle with the issues of support systems for creative artists.” Much of the spirit of exchange at both gatherings was captured in the lyrics of “The Orcas Anthem,” by Welsh video artist Terry Dimmick, with references to the “raucous bunch” that came to “the Orcas caucus.”

Since GIA members are the primary audience for the Reader, it is tempting to draw a straight line from these conferences to today’s active interest in artists support by grantmakers and to GIA’s twenty-member Support for Individual Artists Committee, especially since four of today’s committee members attended. In truth, direct cause and effect, especially in changes over the long term, is hard to prove, not just in this instance but in any effort that does not involve a simple technical fix. Many factors are almost always at play. Certainly, other forces also led to the creation and determined the shape of this cohort of funders. Similarly, while the conferences at Montauk and Orcas surely influenced the focus and growing momentum of grantmaker interest in artists support, the two events also had other impacts.

Who was there?

At both conferences, about a third were artists, ranging from visual artists, composers, media artists, choreographers, poets, and performance artists to critics and theater directors, a storyteller, a woodworker, a puppetry artist, and many others. Their reported share would have been larger if careful records had been kept of artists who also played organizational roles.

Other participants included funders, both private and public, and representatives of a wide range of organizations — artist-centered organizations, arts institutions, advocacy groups, and research centers. People came from thirty-six states and eight countries, from big cities, such as Los Angeles, Addis Ababa, Chicago, and Tokyo, and from small, rural towns, such as Clearmont, Wyoming, and Hotevilla, Arizona. Cultural heritages were expressed through the languages spoken in a short, unscheduled performance at the last evening meal on Orcas: Spanish, Hopi, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Japanese, Vietnamese, Lithuanian, Dutch, Welsh, Icelandic, one of the Ethiopian languages, and I’m sure others.

This mix of people was responsible for some of the impact and notoriety of these conferences. They weren’t designed just for a single set of people — not just artists, not just funders, not just an association of organizations. And people were willing to argue with each other.

Who asked NYFA to take this on?

Well… nobody, in fact. The specific origin of these gatherings lies in the irrepressible commitment and vision of Ted Berger, then executive director of NYFA. Artist Mary Griffin noted, “Ted put his money where his mouth was, even when he didn’t have any.” In 1985, NYFA had taken on the fiscal sponsorship and management of the artist fellowship program of the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA). Berger was eager to learn from others doing similar work, but they proved extremely difficult to find, especially in those pre-Internet days. As Berger said in a recent telephone call, “Nobody knew who was doing what to whom.” Griffin was on contract with NYFA at the time, helping build a committee of artists to be policymakers shaping the fellowship program. “She was really the one who gave me a quick education in the whole artist-centered world,” Berger said. “The conference at Montauk grew out of our frustration that nobody knew what was going on.” It was set in motion by a small grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), which allowed him to hire Griffin as the conference organizer. Among many other things, she gave the conference its generous spirit, balanced with a strong kick of contrariness.

At the time, arts activist David Mendoza and I were scheming the start-up of Artist Trust, and we were both invited to Montauk. Afterward I became a big promoter of a follow-up gathering, and even after “vowing never to do it again,” Berger hired me to plan and coordinate another conference two years later on the other side of the country. At the time, I liked to say I was NYFA’s West Coast office.

Were they fueled only by frustration?

Not at all. The two conference locations may have been remote, both geographically and in terms of communication tools available then, but they were not isolated from the concerns and events of their times. They didn’t emerge in a vacuum; activity was bubbling up in many places. NYFA’s new fellowship program was not alone. Several other state arts councils had or were beginning grant programs for artists. GIA had just begun; its first conference was held in 1985. Art Matters was incorporated in 1985, Artist Trust was launched in 1986, and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts officially began with Warhol’s death in 1987. A few fellowship and funding programs for artists were already active by this time. Among them were the NEA’s artist fellowships in many program areas, the Bush Foundation’s artist fellowships (begun 1976, discontinued 2010), the Guggenheim Fellowships, the MacArthur Fellows Program, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and the Adolph & Esther Gottlieb Foundation. As Berger stressed, however, communication among them was minimal.

At the same time, connections among artists and artist-centered organizations across the United States had been growing through the NEA’s peer-panel review process and through conferences (often also supported by the NEA) of artist-centered groups such as the National Association of Artists’ Organizations (first conference in 1978), the National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture (founded in 1980), the annual New Music America festival and conference (started in 1979 as New Music/New York), and the Association of American Cultures (founded in 1985). The NEA provided critical groundwork. “We couldn’t have done it without the NEA,” Griffin said later. Everyone met each other through its selection process: “It pulled us together and sent us around the country on site visits.” Conference invitations drew on these connections.

Impetus for the conferences also came from concerns affecting society as a whole. These emerged in conference discussions on topics such as the border as a laboratory (especially the US-Mexico border), the concerns of rural communities, the state of arts education and the educational system, bridges between cultures, the rise of the AIDS epidemic, and the value of artists’ activism outside the arts.

Were participants prepared for this?

We did our best to set people up for what to expect. Both conferences commissioned letters and papers by artists, funders, and administrators and distributed them to participants in advance, on paper of course. Among the twenty-three commissioned authors were Thulani Davis, Leslie Fiedler, Anne Hawley, Lewis Hyde, Howard Klein, Ruby Lerner, George E. Lewis, George Ella Lyon, Amalia Mesa-Bains, Nam June Paik, Jim Pomeroy, and Dana Reitz. Most also attended at least one of the conferences.

— Trisha Brown, choreographer, letter to the conference

Artists told life stories of their struggles to make art and ends meet, or, as Robert Ashley put it, to live a life wholly created “on spec.” Artists made pleas for more money and offered lists of new ways to think about it. Martha Rosler wrote of the rising interest in art as investment and of artists acquiring cachet in popular culture, and she advised being wary of cultural homogenization. Many letter writers argued that cultural pluralism and diversity were essential to a healthy environment for art making. Others wrote of tension between large institutions and small community-based groups that supported the development of artists’ work. In “Bucks and Ethics,” Richard Misrach made a plea for ethical standards in efforts to broaden the economic base for the arts. To answer the question, should we do more than just wring our hands at the economics of “art”?, Owen Kelly, British community artist, offered a history of what is called art and the history of its funding in a British context. As a grantmaker, Ella King Torrey observed that much of earlier philanthropy used medical metaphors, like “curing” society and “eliminating” poverty. “Art is neither alleviative nor corrective,” she wrote. “Creating art is an affirmative, generative act.” It should be nurtured and vitalized, not “fixed.”

— Jim Heynen, writer, letter to the conference1

As if the letters weren’t enough, we sent lots of other background materials in advance: articles about specific programs (artist-endowed foundations, programs of support in other countries, and the origins of artists’ organizations), articles about research and publications (such as Joan Jeffri’s Information on Artists project and an overview of university support for artists), and pieces to spark thinking (“Bringing Back the W.P.A.,” “Aesthetic Curiosity: The Root of Invention,” and a declaration of cultural human rights). Advance materials were not discussed directly, but they meant everyone was well supplied with context and touchstones for conversation.

But what really happened when people got together?

In addition to the conferences’ isolated locations and the mix of people who attended, the structure of these meetings offers a key to their impact.

Art was integral. There was music and dance, poems and stories, readings, performance art, and video showings by more than thirty artists, paralleling the diversity of the conference as a whole and with artists of many disciplines and cultures.

The aim overall was to create a forum for thought within the context of the art itself. At Montauk this meant not structuring the day-and-a-half-long meeting around panels, lectures, or the recitation of prepared papers with the requisite question-and-answer periods. Rather, all participants convened in plenary without an agenda, broke into smaller discussion groups, and then reconvened to further consider and debate the ideas that emerged. As the summary report stated:

This unique structure, or lack of it, made for an extremely involving, and often frustrating, conference. Conference participants were denied the possibility of settling into the role of passive audience… The agenda for action had to be discovered by the participants as they talked and thought together.

The agenda on Orcas (this time a full three days, longer if travel is included) was more formally structured. Panels were avoided, though, and, like at Montauk, no specific actions or outcomes were identified in advance, and impromptu sessions and activities were encouraged. A full schedule of talks, small working groups, plenaries, and performances prompted fervent impromptu speeches, intense discussions, proposals for action, disagreements, challenges, inspiring examples, and new ideas. And people listened to each other, sometimes in rapt attention, sometimes with great frustration, sometimes with imagination and new understanding. Ultimately, the substance of the gatherings relied on participants themselves.

Throughout both conferences, food and drink flowed, and conversation was nonstop — over meals, between official sessions, in the spa and indoor pool, during walks along the beach at Montauk and escapes to the top of Mount Constitution on Orcas. Afterward I learned of “Scotch hose treatments,” seaweed ocean wraps, and who-knows-what goings-on in the woods. After the Orcas conference, artist Ellen Sebastian noted, “in the Baptist church this is sometimes called an ‘experience meeting.’”

That’s all very nice, but what did you actually talk about?

Discussion ranged across more topics than seem feasible in retrospect, many of which will probably seem familiar today. Some of the talk at Montauk was fairly abstract, for instance, about the role of art and artists in our society, the essential part art plays in the creation of social meaning, and the lack of recognition for artists’ contributions. Analogies were drawn to research and development in the scientific community and to think tanks in the worlds of politics and economics. Discussions considered the social utility of artists and the position of artist as outsider or of artist as criminal. Talk also turned practical: how can artists and administrators best lobby legislatures? What support is needed beyond cash grants? How can new sources of funding be found?

The number of individual “working sessions” at Orcas was dizzying — six or seven at a time in each of four time slots — each one organized, led, and summarized for future reference by participants. There were discussions on artists and institutions, artists and communities, artists and corporations, artists and state arts agencies. Other sessions also focused on funding: methods for selecting artists for grants; sustained multiyear support for artists; the introduction of a new guidebook, Money to Work: Grants for Visual Artists; and artists and trends in corporate philanthropy, which suggested that the next phase of corporate philanthropy would be especially sympathetic to artists. “Toward a national arts policy,” a new and unsettling concept for some, began with a broad discussion of what such a policy might be but turned to a more specific task of identifying qualifications for new presidential appointments to the NEA.

Some discussions veered away from financial support and took up other practicalities: advocacy by and for artists, artists’ space needs, artists’ human and social service needs, artists’ education and arts in schools, the role of criticism, and “audiences and the communication of meaning.” A powerful early addition to the conference agenda was a statement about AIDS by Renny Pritikin, codirector of New Langton Arts. It inspired adding a working group — AIDS: No longer “other business” — and a second statement by Mendoza. Several working groups were based on questions: Does public art offer new roles for artists? What has happened to US composers in this century? Is a national funding aesthetic truth or rumor? Another, partly in response to Lewis Hyde’s keynote on the gift economy, asked, Does philanthropy lack the spirit of gift exchange?

Themes of cultural pluralism and diversity threaded through the conference, reflected in sessions such as “Building bridges between cultures — the artist’s role” and “The border as artistic and intellectual laboratory,” and in topics such as Southeastern Native artists and artisans, current research on Afro-American art, and issues facing rural artists.

An eleven-member Latino Caucus, formed during the conference, took advantage of their “fortuitous meeting” on Orcas Island and addressed “the large challenge of self-definition.” Through exchanges during and after the conference, a special report was produced by caucus members with sections by artist Amalia Mesa-Bains and National Council on the Arts member Robert Garfias. The report addressed representation, education, training and development, aesthetic foundations, and folk and traditional arts. The report also included a draft document by performance/visual artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña that later became his “The Multicultural Paradigm: An Open Letter to the National Arts Community.” Among other topics, he discussed “The Latino boom”:

And what else did artists have to say?

A lot. Artists participated actively throughout both gatherings. Also, in response to an undercurrent of pent-up energy from artists, a plenary session at Orcas was redesigned to give them a specific chance to vent frustration, challenge ideas, and make proposals. Twenty-eight artists spoke. They critiqued the conference. They critiqued grantmaking systems as they experienced them, often expressing disillusionment with the process. They told stories about their own lives and how they support themselves. They spoke to the need for funding sources and presenters to continue being sensitized to cultural and aesthetic otherness. They warned of the appropriation of artists’ work by corporations. They also said the following:

— Michael Anania, writer

— Peter Garland, composer

— Margaret Fisher, choreographer

— C. T. Chew, visual artist

— Ed Shay, visual artist

— Mary Griffin, artist

Alberta Arthurs, director for Arts and Humanities at the Rockefeller Foundation and moderator of the session, summarized what she heard:

In the midst of all that, did anything lasting happen?

Depends on your expectations. At one point during the conference at Orcas, Howard Klein, former director of Arts and Humanities at the Rockefeller Foundation, spoke of getting “intellectual dyspepsia” from the number of issues before the conference. In a letter to Berger afterward, he wrote that the experience did not give him the sense of building momentum he would have expected of a second conference. Despite “all the right issues” being on the list, he was unable to determine “where the agenda hoped to lead us as a group.”

In fact, neither conference was designed with specific ends in mind. During a recent conversation, Griffin, organizer of the Montauk conference, described herself at the start thinking, “I’ll invite some nice people with intelligence and experience, and we’ll see what happens.” This approach was reflected in the open, agenda-less form she established for that gathering. A similar openness pervaded the agenda for Orcas, with its overflowing menu of topics and a flexible premise that welcomed additions, critique, and adjustments.

At the same time, the open structure allowed many things to happen. For example, as the Montauk conference summary noted, “One group of self-designated ‘power brokers’ from state agencies, the NEA, and foundations reported that they had met and had plans to meet again to find ways to convince each state to create individual artist support programs and to develop mechanisms for multiple-year support programs.” Through Berger’s expert shepherding, by the time we met at Orcas two years later, a seven-state National Consortium for Individual Artists announced receiving $800,000 from the NEA, matched three to one by participating agencies and with additional private funds beyond that.

— Ella King Torrey, The Pew Charitable Trusts

It was then, Griffin said recently, that “program officers joined the party.” And Berger added, “Ella [King Torrey], for one, was unbelievably involved.” After attending both conferences, she went home, committed to doing something; in 1991 the Pew Fellowships in the Arts was founded to support Philadelphia artists in a significant way, and the commitment continues today. Jean McLaughlin, visual arts/literature director, North Carolina Arts Council, reported feeding insights from Orcas into the council’s long-range planning process. Among others, she said, “we are establishing a new design arts category, strengthening our initiatives in criticism, artist forms, commissioned new works, and direct grants to artists… All colored by the words, inspirations, and aspirations from the Orcas meeting.”

As the Orcas conference closed, Berger recalls our asking, “How can we continue this conversation across disciplines, across the country or internationally? Remember, this was before the Web.” A newsletter, maybe?, he suggested. I knew there had to be a better way than one more news-letter. So I launched myself on a journey to learn about what was then called the “information and communication superhighway.” In 1989 the world of computer communications was full of big ideas and political passion. The result of my investigation was ArtsWire, an early online computer network used by artists and the arts community across the country. With Berger’s leadership, NYFA adopted it, despite his being, as he liked to say, “of the quill pen generation.” Sarah Lutman, then executive director of the Fleishhacker Foundation and a member of the Orcas invitation committee, along with many others met through the conferences were critical to building the network.

Can you point to other direct impact?

Not much was direct. Whatever the results are deemed to be, they were not due to strategic, coordinated efforts of the whole but rather were products of specific people who were inspired and then took action within particular contexts. As Lutman said recently, “It wasn’t, let’s all get in a room and pool our money and do something national together. It was, how do each of us within our own constraints and possibilities advance a cause that we collectively care about?”

Fueled by shared interests and individual drive, ideas and connections spread. For instance, during the spontaneously organized working session on AIDS, participants drafted a set of recommendations for action and got a resolution endorsed by the full conference. A few days later, the same recommendations were presented at the annual meeting of the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies, and a similar resolution was adopted. Session reporter David Fraher, executive director of Arts Midwest, wrote, “So there it is. Ad hocracy leading to public resolution, and, we trust, to public action in the long run.”

In a recent conversation, Mendoza emphasized the human connections. In his experience, simply talking about artists in an organized way was new. “Everyone was interested, everyone contributed.” The guest list created, he suggested, “a large context — geographically, hierarchically, and in terms of age, race, and profession.” Lasting networks and friendships were created across these bounds. Individuals in various configurations established bonds that became essential to their subsequent work. For instance, Mendoza said, being able to draw on these networks a year or so later was critical to building the National Campaign for Freedom of Expression, especially since email was not in common use at the time.

The conferences made many ripples, Berger said. “One gathering led to others. Montauk sparked Orcas, and Orcas sparked regional discussions.” Two regional gatherings were designed specifically to inform the agenda of the Orcas conference, one in Philadelphia (May 1988) and one at the Headlands in the San Francisco Bay Area (August 1988). A series of smaller meetings sprang up afterward — at Penland School of Crafts, at the Fleishhacker Foundation in San Francisco, at La Napoule, France — and probably more.

Energy also spread among funders, and their attendance increased significantly between Montauk and Orcas. “Montauk was infamous,” Peter Pennekamp, then at the NEA, said later. “So when an invitation to Orcas arrived, I quickly accepted.” In my interviews, both Berger and Lutman emphasized that these were developmental times for the field of arts funding as we know it today. Having started in 1985, GIA was still very young. I began attending GIA conferences in 1991 as coeditor of the GIA Newsletter (now the Reader) and found members there who had attended or heard about the two conferences. In a year or two, we were organizing, first breakfast roundtables and then preconferences on support for artists.

Isn’t artists’ work still an economic puzzle?

Absolutely. Much of the talk at these two conferences was about grants and the role grantmaking can play in an artist’s life. Indeed, the impact of philanthropy and gift exchange can be huge. But we also heard a lot about the many ways artists hold their financial lives together. Writer Jim Heynen captured what many artists experience:

Lately, I have become interested in the nature of work and how it’s changing, inspired primarily by my life among artists but also by a cursory knowledge of the Open Society Foundations’ two-year initiative on the Future of Work. From Carl Camden, CEO of Kelly Services, I learned that some 43 percent of working Americans don’t have “a job”; that is, they have work, but they aren’t traditional “employees.” They work as part-time or temporary workers, independent contractors, self-employed professionals, and consultants. The percentage, Camden says, will be closer to 50 within the next year or two. The life he describes sounds very much like the life Heynen and many artists live. Perhaps others can learn from the way artists have done it. Lutman commented that at both Montauk and Orcas she watched people “who lived by their portfolios,” and she didn’t mean grant portfolios. “The artists invented their jobs from day one.” It’s what many of us do now.

Even when piecing a work life together effectively, there is still the question of value. I am currently hosting a conversation series on the nature of work, attended primarily by people not directly involved in the arts. A question that kicked off our first session was, What work is valued? After discussion in small groups, we had a new question: Why does the most valuable work pay the least? Participants were thinking of health care workers, teachers, and child care, but the same question persists in the arts. Robert Ashley wrote in his letter to Montauk: “I have run a very successful small business for over 25 years. But I forgot to be paid. Well, I didn’t ‘forget’ — it would have been impossible.”

Frances Phillips’s article “Valuing Labor in the Arts,” in the fall 2014 Reader, comes to mind. In introducing a new publication and a practicum on the subject, Phillips described her previous work directing an alternative art space: “the amount of effort we expended and the quality of the product we produced had no bearing on the money we could earn or raise.” And she added that the organization’s conundrum, “mirrored the weak connections among labor, effort, intellectual contribution, aesthetic value, and money that hobble many artists.” My experience suggests this hasn’t changed much.

So what should we be thinking about now?

First, it is important to acknowledge that artists do not face their economic dilemmas alone; they are part of a much larger system that extends way beyond the arts. And that system is changing. I am betting we have much to learn from other fields, and I am convinced that we have valuable experience, knowledge, energy, and imagination to offer a larger dialogue.

In an observation that remains relevant today, Lutman said that the conferences reinforced her belief that when working in any field, “the generative people have to be with you.” Using a geology metaphor, she said, “It’s like tapping into an underground water supply, a way to connect with what is already and always in motion.

From another perspective, the experience proved to Mendoza how important artists are to a democracy. Living now in Indonesia, a nascent democracy, he sees how important gatherings like these could be. In retrospect, I recognize in them some traits essential to a democracy: a forum that allows all voices to be heard and one where differences can be expressed. A recent exchange between Griffin and Lutman reflects these traits:

Sarah Lutman What was different then is that there was no prescription on what the world needs. A concern for artists was a bigger platform than what we see at convenings today.

MG And, in those days, artists were prepared to bite the hands that fed us.

SL Everybody is just way too polite today.

Creating opportunities to connect with each other, to talk and argue together, to be face-to-face with different perspectives is valuable. And the structure of those opportunities matters. With these two conferences, “it wasn’t just connecting with each other in the way we think of it today,” Lutman stressed, “where connections are often through social media.” We spent really significant time together, stuck on a bus in terrible traffic or on a boat in rocky weather to get there, and we arrived in remote places on islands with no PDAs, laptop computers, nearby shopping, or other easy distractions. “We had long periods of uninterrupted time that allowed real conversation that was deeply considered. And performances were intermingled.”

— James Yee, executive director, National Asian American Telecommunications Association

Real conversation requires that everyone feel equal as a participant. Both Mendoza and Berger emphasized that at Montauk and Orcas people were brought together as equals, though with undeniable differences: some had resources, others needed them; participants came from different cultures and had different backgrounds and roles; the power differential was still present, and some felt patronized or not respected. I can say we tried to create a ground that was as level as we could figure out at the time, and we heard that many benefited from our efforts.

Everyone had essentially the same accommodations and ate together in the same dining room. No “stars” were scheduled to make cameo appearances. Perhaps counterintuitively, attendance by invitation meant the conferences could be inclusive of a wide diversity of participants. And we accommodated varying economic capacities by having a flexible financial structure: some paid a conference fee as well as their travel and lodging costs; artists had their costs covered and were paid a fee to participate; and others fell somewhere in between depending on their circumstances. Perhaps the level of debate and the more equitable “push and tug” observed by Yee is an indication of our having a degree of success in providing a context where speaking up was part of the deal.

There is real value in stepping outside our everyday lives. We need times to come together, to think and argue together, and to push toward new possibilities without big expectations, as Griffin said in planning the Montauk conference, “to see what happens.”

Is there no end to this?

Yes, yes. This essay will finally end. But in a larger sense, the dilemma of creative support for artists may have no end. As Berger told me:

He closed with a nod to two literary sources: “Nothing’s permanent. I’m always tilting at windmills, and I suppose I have to accept Godot’s dilemma: I can’t go on. I must go on!”

In the session at Orcas about artists’ role in building bridges between cultures, artist Adrian Piper spoke with a relevance beyond that session. She referred to solving problems laden with painful anxieties: “We have to start as individuals, without agendas. The important thing is not who we are or what firm we’re from, but an openness and willingness to trust the future. It’s hard — it means giving up control.”

Author’s note

To help pull these two conferences back into memory after nearly thirty years, I have drawn on two main sources. First, Ted Berger, Mary Griffin, Sarah Lutman, and David Mendoza, each of whom attended both conferences, took time to talk with me and bring their own perspectives to bear. We barely got started, and I know many other people could have shed light on the two events and their value. I also drew heavily on the fat notebook of materials produced as a result of the conference on Orcas Island. Complete books contained almost five hundred pages.

I haven’t tried to update the affiliations of participants. The affiliations included here are what was current at the time. And as is inevitable with the passage of nearly thirty years, several people mentioned or quoted here have died; it was hard to resist the temptation to offer the tributes they deserve.

A selection of background materials from the two conferences is available online at: www.Montauk-Orcas.net.

NOTES

- Jim Heynen, “But Is It Expedient?,” written for the Orcas conference, published in GIA Reader, summer 2002, http://www.giarts.org/article/it-expedient.