The Future and Our Role in Shaping It

Summaries from the Funder Peer-Group Discussions at the GIA 2009 Conference

INTRODUCTION

— Ronald Heifetz, Alexander Grashow, and Marty Linsky

In the midst of the current economic turbulence, GIA feared its 2009 conference might be poorly attended. The opposite was true. Attracted by the opportunity to gather with colleagues seeking solutions to problems of unprecedented magnitude, more than 400 grantmakers and arts professionals from across the country converged on Brooklyn.

GIA’s new leadership believed this conference should boldly address the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead and the role of arts grantmakers in shaping the future. We hoped for a generous exchange of ideas and strategies, and were not disappointed. This article is informed by 664 pages of written comments gathered from 246 participants and 110 pages of notes from peer group discussions. While quantifying opinion is far from a perfect science, we went to great lengths to see that this article fairly represents the most critical issues identified by those arts grantmakers and service providers participating, as they strive to make sense of these times and act responsibly to ensure that the cultural sector thrives.

We hope the results will be useful to grantmakers and service providers as they strategize for the future.

METHODOLOGY

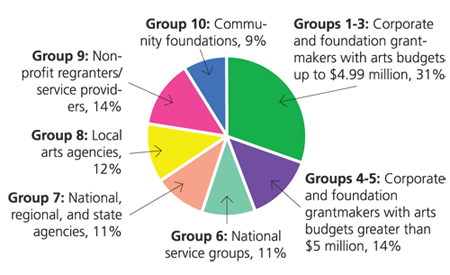

With guidance from a small design team, conference participants were pre-assigned to ten peer groups defined by structure and size: corporate grantmakers; foundations; national service groups; national, regional, and state arts agencies; local arts agencies; nonprofit regranter/service providers; and community foundations. Peer group size was intentionally small, some 15 to 30 participants including professional staff and board members. To ensure that all voices were heard, each group’s discussion was facilitated and documented by respected peers. Two broad questions were posed:

1) Given a healthy cultural sector in the year 2020, what are you, as a grantmaker or service provider, doing, or starting to do, in 2009 to contribute to that success?

2) What were your priorities and who were your partners?

The intent was not to reach consensus on what would constitute a healthy cultural sector by 2020, but rather, given each participant’s own vision of that future, to generate strategies and actions that might ensure its success. Questions were intentionally broad so as not to be prescriptive. We believed this session would be valuable, if only for affording usually isolated peers a rare opportunity for honest, safe dialogue.

This chart shows the representation of peer group participants whose input contributed to this article.

| CONFERENCE PEER GROUPS |

|

THE GRANTMAKERS’ WORLD

Funders occupy a unique niche in the complex ecology of the communities they serve. It is no surprise that even the most surefooted arts grantmakers feel challenged by the complexity of the situation. Arts grantmakers are being sought for support and solutions at a time when they themselves are faced with significant challenges:

- Creativity and arts consumption in the wider culture are soaring, but often in realms outside what arts grantmakers support. How can funders foster cooperation between for-profits and nonprofits to avoid working at cross purposes?

- Arts grantmakers believe in the power and promise of the arts to enrich people’s lives. However, and especially in this recession, the gap between the cultural sector’s potential and the ability to realize it seems ever wider.

- In large measure, cultural sector funders have influenced — and continue to influence — the field and set direction by what they support. In this digital age where the 2.0 world contributes to setting direction, how can ground-up processes contribute to setting tomorrow’s priorities?

TEN STEPS

The peer group sessions’ first question, “What are we doing, or starting to do, to ensure the cultural sector succeeds?” elicited 1,441 written tactics, strategies, and ideas from participants in all ten groups. These responses were divided into 58 categories. Discussion notes collected from each peer group session provided additional context, and the 58 categories were merged into 10 broad areas. GIA participants stated imperatives to:

- Pursue excellence in grantmaking

- Focus on relevance

- Continue support for individual artists

- Increase stewardship

- Eliminate silos through convenings, collaboration, and connection

- Leverage resources and influence within and across sectors

- Communicate effectively

- Lead by example

- Foster self-reflection and working smarter

- Strengthen relationships with grantees

1. Pursue excellence in grantmaking

Grantmakers must understand and demonstrate the impacts of what they fund. Diminishing resources and competing priorities emerging in communities are pushing everyone to question and reassess: What must be fortified? What needs retooling? What does not exist, but needs to? What is unique and critical, and what is duplicative? What has dwindling relevance in today’s challenging times and should be mothballed, jettisoned, or ended?

At a time when arts program funding within government and foundations is being reduced or subject to wholesale elimination, arts grantmakers are scrambling to ensure that funding intent and funding outcomes are aligned. One foundation officer said it best: “We can’t achieve our mission without our grantees achieving theirs.”

Examining funding priorities

Many arts grantmakers are revisiting their definition of the cultural sector and revising their picture of sector success and health. Grantmaker stances run the gamut from holding firm to current funding priorities to completely revamping them. One person spoke of broadening the foundation’s definition of what counts as art. “For the first time, we are funding and nurturing individuals, organizations, and community-based organizations that are making and sharing work in ways we’ve never seen before.” Others firmly believed that changing course in the midst of a storm is ill advised. “We are hunkering down and doing whatever is necessary to see that our grantees doing the critical work in our community survive.”

Still others are taking the side of economic theorists who believe in recession’s “creative destruction.” These arts grantmakers are making changes in funding policy, knowing organizations will decline, possibly terminally, while others will emerge and become the driving forces of cultural activity and growth.

Peer group discussion was the most honest, intense, courageous and self-critical when focused on arts grantmakers’ aspirations in light of their historic practice:

- “We speak of being part of the global environment, but do our funding policies and practices reflect it?”

- “When are we going to face the fact that much of what we’ve supported for years is racist? According to our funding criteria, many culturally specific organizations have never been eligible to apply.”

- “Are we here to support established organizations, or are we here to encourage and fund creativity in our communities? We talk of funding innovation, but who among us does?”

- “We expect grantees to program in ways antithetical to our own funding practices.”

- “If we believe in the contributions of an organization to advance an art form, why aren’t we paying more attention to their administrative and fiscal health? Many among us look no further than artistry.”

- “When are we going to acknowledge the misstep we may have made in the move away from general operating support? An unintended consequence is that we’ve become more, not less, prescriptive, and have been the curators of what gets produced.”

- “Administrative funding caps on project grants have contributed to organizational destabilization.”

- “If the sector is successful in 2020, it will be because we in the foundation sector stopped supporting organizations that are tone deaf to demographic and economic changes that will make the next ten years fundamentally different than the last.”

- “We say the sector needs to evolve innovative structures, but have any of us modified our guidelines to fund them?”

- “Is the information we ask of applicants pertinent to the success of the project? We ask for strategic plans, but how many of us actually converse with our applicants to learn if there is rigor in plan implementation and outcomes actually achieved?”

- “We’re critical of grantees and the extent to which they’re connected in the community, but what about us? We’ve isolated ourselves — the ‘oh precious, precious syndrome’.”

- “Fundamentally, we ourselves don’t innovate, and we’re likely holding the nonprofit organizations back from innovating themselves.”

Given these opinions and self-criticism, peer group sessions focused on the imperative to change not only what is funded, but how.

Policy changes for consideration

Grantmakers reported assessing policy in these and other ways:

- Focusing on models of business and new capitalization, leading to new ways of operating and funding.

- Narrowing the spectrum of organizations funded. One representative of a small foundation funding individual artists and small and midsize organizations said, “We’re getting more specific, instead of letting a thousand flowers bloom.”

- More thoughtfully integrating community values and cultures into funding priorities and focusing on models and development of funding programs to advance principles of art and community building.

- Creating new opportunities. Some funders are also holding fast to commitments to fund general operating support.

- Ensuring the needs of small, and midsized organizations are being addressed — especially artist-centered organizations and incubator organizations.

- Relaxing the boundaries and borders of arts disciplines to encourage thinking about the arts more broadly rather than within rigid categories.

Procedural changes for consideration

Many grantmakers commented on refinements they are making, or plan to make, in grant making procedures. A sampling:

- Thinking beyond the programmatic and supporting what keeps organizations growing. Whether organizations are seeking general operating or program support, assessing programs, operations, and finance with equal rigor.

- Looking more carefully to see that basic infrastructure needs of applicants are in place — from healthcare and living wage compensation to retirement benefits.

- Exercising more flexibility in timing of grant payments.

- Repurposing existing grants to general operating support if that helps the organization

- Providing extensions or renewals with no formal proposal needed.

- Adopting simplicity and flexibility as the new modus operandi to accommodate the cultural sector’s realities.

2. Focus on relevance

Many grantmakers are challenged to support those who provide content that has meaning and value to consumers via delivery systems that are accessible. In the eyes of consumers, relevance is excellence.

One of the greatest challenges facing arts grantmakers is helping the cultural sector ensure that arts supply aligns with and anticipates consumer demand. If earned income and audience numbers are measures of the relevance of the arts, funders realize there’s a great deal of work to do. The arts market place is ever expanding, offering new experiences and new ways to consume them. “Digital media has revolutionized the way art is created, curated, distributed and consumed.” “Kids think YouTube is an art form and everyone is an editor.” Proliferation of commercial offerings has had a seismic impact invigorating a worldwide audience in performing arts. Examples mentioned included So You Think You Can Dance, Glee, American Idol and more. One grantmaker said we should be thrilled that arts consumption is flourishing. “It’s just that it’s not the arts we support.”

Some grantmakers are more holistically combining marketing and programming. “Effective messaging and good PR will attract audiences the first time, but it will be relevant program content that keeps them coming back.” Engage 2020, an initiative of the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance, is one example of market research results being used by organizations across the city to develop programs that will double arts audiences by 2020.

Continuing support of arts education

— Foundation officer with a grantmaking budget greater than $5 million

Frustrations of working in public school settings aside, twenty percent of all conference peer group participants believe that support of arts education, programs focused on youth, and life-long learning will continue to be critical in building cultural literacy and expanding the consumer base for the arts. Some grantmakers have shifted funding from in-school arts education programs to after-school or other arts programs serving youth and under-reached populations.

Making the arts more central to communities

Some funders are supporting (or exploring support) of non-arts community-based organizations to serve populations in their communities that arts groups are not reaching. In each of the ten groups — particularly public funders, service providers and local arts agencies — lists of strategies to better integrate the arts into the community were shared and included arts organizations, artists, and arts workers as emissaries.

Some foundations are funding artists as workers in community-based settings. “Artists are valued teachers and spiritual leaders. They inspire and communicate values through their work and activities.”

The essential role of the arts in social justice and civic engagement

Session participants praised social justice and civic engagement preconference sessions. When we reviewed individual participant responses we found 16 examples of current or planned strategies in place to address social justice. One participant commented that social justice is “just the new euphemism for multiculturalism. After so many years, we are still mired in language and discussion about inequality, but not doing nearly enough to address it.”

3. Continue support for individual artists

Artists — all creative individuals — are the “molten heat.” Without artists there is no art, no inspiration, no sector.

Grantmakers are focusing on artists of every discipline, artists of color, emerging artists, artists’ collaboratives and artists’ colonies. Grantmaker resources, effort, and energy will continue to tend to well-being of artists.

Strategies to support artists

158 strategies to support artists were listed by participants and included various dimensions of these broader areas:

- Access to health care and retirement benefits

- Professional development

- Promotion and marketing

- Job creation

- Partnerships across all sectors

- Research

- Residencies; fellowships; international exchange; and commissions

- Loans, training, and travel stipends

Examples of strategies to support artists beyond funding included:

- Providing additional support to arts organization to hire artists

- Finding new ways to position artists as democratic visionaries

- Using artists as mentors

- Training artists to become administrators

- Support of artists’ incubators

One foundation spoke of a recent board-approved change in funding priorities putting artists in the center of their program. “The way we now talk about the cultural sector focuses on opportunities for artists rather than how institutions can survive. As long as we are keeping those working artists at the center of what we do, we are not as concerned about what happens to any given organizations that in the past we felt were so indispensable.”

“Another grantmaker offered, ‘When I look at budgets, I ask where the artists are. Part of our funding criteria includes the extent to which organizations are working with artists.’”

4. Increase stewardship

Top of mind for arts grantmakers is what can be done beyond the financial investment to ensure the well-being of grantees. Grantmakers are concerned with the fragile state of the sector, and, to a degree, frustrated that strategies to strengthen the sector over the last decade have shown only limited results. A battery of strategies to strengthen organizational stability was shared:

- Administrative capacity-building

- Financial literacy and capitalization

- Promoting effective governance

- Mission-appropriate revenue generation

- Leadership cultivation and retention

- Provision of mentors and coaches to all staff members, even boards of directors

- Professional development

- Experimentation with business models to propel innovation and creativity

Increasing sector capacity-building services. Some grantmakers are partnering with nonprofit and for-profit professional development providers such as universities, community colleges, institutes, and local leadership development programs to support grantees. Others are retaining consultants or bolstering the ability of discipline-specific service organizations to deliver more capacity-building services.

Strengthening financial literacy, stability, and capitalization. Numbers of funders are realizing that the sector must become more financially self-sufficient and that continued funding of artistically excellent organizations with dangerously lopsided earned-contributed income ratios and precarious balance sheets must change. One foundation officer said, “We’ve unintentionally spawned a generation of donor-dependent organizations as opposed to market-dependent organizations. Looking forward, it is a formula for disaster.

- New capacity-building initiatives will encourage exploration of mission-appropriate revenue generation and increase organizations’ base of support.

- New tools developed by the Nonprofit Finance Fund are designed to strengthen the financial capacity of nonprofits. One particularly important element enables organizations to assess the adequacy of its staffing. “Too many organizations run too lean, and it is a major cause of burnout.”

- Some grantmakers are requiring new arts grantees to establish a rainy day fund policy.

Strengthening sector leadership

Funders realize there is no substitute for strong sector leadership and that a priority is to do whatever is possible to attract and keep good leaders in the field. “It is a significant problem with community-based organizations. Many of those leaders are looking to retire, though have no resources to retire with. The fragile resources of these organizations and low salaries, means no one wants to go into the organization. Today’s mindset is different from the public mission that attracted the previous generation of arts workers.” Another spoke of this same problem facing boards. ”What are we doing to develop the next generation of board leadership?”

One corporate foundation representative spoke of the importance of encouraging development of leadership teams in arts organizations as a next best practice. “We’ve seen too many examples of executive departures that have brought organizations to their knees.”

Encouraging innovation, new models, and new programs

There was a lot of buzz about the need for new models, and some urged more support to the best and brightest to develop innovative models or looking to other sectors for models. But even economists caution that evidence on adopting business strategies to manage through recession is patchy. Strategies can be risky; organizations are likely to be too preoccupied with short-term survival to think about innovation and growth, or they lack the resources to implement such strategies effectively. One public funder posited, “The nonprofit model is not dysfunctional; it’s the funding process that’s dysfunctional. We need to move from grantor/supplicant relationship to more of a partnership.”

5. Eliminate silos through convenings, collaboration, and connection

— Morten T. Hensen

“It’s time to step out of our silos.” Every peer group spoke to the advantages — and need — to being more connected and aware of what is going on around them. A range of strategies was mentioned:

- Convene and participate in dialogues with artists and arts organizations. “There is some important work happening in our community around capacity-building and arts education. We’re creating opportunities to work significantly with grantees on these areas — learning alongside them.”

- Connect and create more public/private partnerships on common issues across communities. “We are seriously committed to building coalitions with partners in a range of issue areas — education, economic development, environmental sustainability, human rights — to advocate for public resources that support strategies which included the arts as inseparable elements of their success.“ “We gather two or three times a year with the other funders in our state, and those discussions play a critical role in making decisions about setting strategy, and making sure we are working in tandem.”

- Connect with the community and non-arts interest areas. One foundation convened its entire staff to determine what community partnerships were most important to be listening to. “What entities or community leaders had their finger on the pulse of community priorities, and how could we connect with them?”

- Connect with new grantees and grantee communities. Foundation staff are making a concerted effort to get out into the community and learn what organizations are doing effective work, rather than waiting for those organizations to come to them.

6. Leverage resources and influence within and across sectors

It’s time to step up. For decades, policies prohibiting political advocacy or taking positions on community issues kept private and corporate foundation grantmakers neutral in the eyes of donors and stakeholders; however, grantmakers agree, the time has come that there is more at risk by remaining silent.

Arts grantmakers are becoming more involved in political advocacy

One grantmaker spoke about the experience of testifying before the legislature on behalf of the state arts community for a new state arts fund. “Our foundation president testified at a key moment and that was crucial to the success of it. It was hard for the state’s arts advocacy organization to find a foundation that would go to bat, but we can do that, and more of us should.”

Arts grantmakers are more proactively leveraging resources and influence

With the new changes in the federal government, grantmakers are looking at ways to leverage (or advocate for) federal funds that can help their organizations and communities.

Others spoke of the value in working on the ground in their communities beside their grantees to leverage helpful relationships with business, industry, planning, or other foundations. “Our presence and our voice could expedite results that would take the sector months.”

A local arts agency leader suggested cross sector research to learn about the value of the arts in other sectors. In addition to the findings, it would be an effective way of cultivating champions for the arts.

PRIs were suggested as an untapped resource the arts sector has not taken advantage of, but should.

7. Communicate effectively

“There is a hunger out there for having grantmakers just listen.” Participants spoke of the need for new platforms for communication and improved communications on multiple levels.

Communication within our own organizations. Many grantmakers identified their own organizations as the first place to improve communications. “Beyond informal exchange, we developed an internal communications strategy to ensure continuous learning, more frequent exchange, and to stay attuned to the realities of constituencies and communities the foundation serves. Up till then most of us confessed ignorance about what was going on down the hall.”

Communication with other funders and colleagues. One representative of a smaller private foundation spoke to the need of greater communication between national and local grantmakers. “Local foundations can be important field officers for national organizations…. Kresge did that with us. There seems to be a giant disconnect, a hierarchy of national verses local.” “It may not be intentional, but it is hurtful.”

Communication in the community. One national funder spoke of the value of working closely with local communities to learn what they have identified as their needs. “I have strengthened communications with our foundation’s officers in 22 states; I am getting them to understand the significance of community-based cultural organizations to improving schools, neighborhoods and more. You can’t have the Art Institute of Chicago go into the Pilsen/Little Village community to provide services, when the National Museum of Mexican Art is already in the neighborhood doing that work.”

8. Lead by example

A common thread among all peer group participants was the responsibility to lead by example and model the behaviors and practices expected of grantees.

Numbers of grantmakers expressed gratitude to GIA for its leadership in convening this forum, enabling peers of similar structure to have open, honest discussion about their foundation’s practices and policies. “The opportunity to share vulnerabilities and find that I was not alone was a tonic.” Another small foundation officer remarked, “I feel vindicated. For years I thought I was alone struggling with many of the leadership challenges aired at this conference.”

Grantmakers are looking at everything from staffing and systems to process, though some participants expressed frustration about the extent of change they’ve actually been able to affect. Other grantmakers expressed impatience with the pace of change within their own organizations, fearful that it is not happening as fast as is needed.

Strategies to shore up internal systems, skills, programs, and processes

Foundation learning needs to be elevated. In order to affect positive changes in their communities, foundation staff and board members must increase their awareness and knowledge of existing in-house resources and use them. “Change has to happen within before it can happen outside.” One grantmaker spoke of his foundation’s “dinosaur mentality.” Though the foundation had successfully created cross-programmatic teams, it was very difficult to move beyond the silo mentality that persisted.

Boards and staff should be unified in philosophy and practice. “Especially among our foundation board, we’re trying to shift the thinking of funder value to the value of what the field is providing.” Many reiterated how important it is for boards to understand what is funded and why. Understanding the community impact of community-based organizations and shifting silo-based thinking to a more integrative culture has been a challenge. “It is on our shoulders to see that our board understands the arts ecosystem in this community (not the elevated part, but the fact we are part of the food chain), and sees why our funding is critical.” That foundations not talking enough or doing enough about the use of foundation assets was also a criticism.

Board representation. Some grantmakers are changing board composition, expanding representation on boards and advisory groups to include artists and others outside the arts field.

Better anticipating implications of our actions. In the midst of reevaluating and shifting priorities, it is important to discuss our decision, plans, and rationale with all those directly — even indirectly — impacted. One grantmaker of a large foundation told of the inadvertent negative impact their foundation’s full-scale evaluation had on their constituents. “It’s not the proposed changes were ill-advised, but we should have communicated in advance with all our constituents what we were doing and why before they heard about it in the street.” “How would we have felt were the tables reversed?”

9. Foster self-reflection and working smarter

In the same way grantmakers expect grantees to increase self-reflection and work smarter, so must grantmakers.

The importance of studying impacts. Now more than ever, grantmakers should clearly understand impacts of what they support. “A grantee may believe outcomes were achieved, but do the constituents for whom programs were intended feel that way, too? We don’t currently have any way to test that.”

Using good research to inform and guide decision making

Sharing information. A national service organization suggested simple ways to expedite information sharing so as not to duplicate research and data collection. “There is a tremendous amount of reinvention of the wheel. If we don’t share information about what exists, we will work harder and continue to stay behind.”

Increasing use of The Cultural Data Project (CDP). Given that CDP has been around for four or five years, grantmakers in a number of peer groups believe it should be more of a field-wide tool helping organizations to compare themselves with others. Using CDP information should also be helping more grantmakers better understand how creative sector grantees are doing and what support to the sector looks like, especially financially. One funder questioned if the CDP could be hindering the field’s ability to innovate out of the 501(c)(3) model. “This may already make CDP an outdated model of supporting organizations, given it reinforces the status quo.”

Applying innovative practices from other sectors. Some suggested GIA’s increased networking with other national grantmakers associations as a good place to start.

Using new media more efficiently. Webinars, Skype, free conference calls, social networking mechanisms, Twitter, etc. might lower operating costs and make information sharing much less expensive.

10. Strengthen relationships with grantees

The final theme emphasizes participant thinking about funder-grantee relations and how increasingly important they will be to future success. Far beyond communication, grantmakers must find ways to build relationships and trust. Some blamed old funding structures and practices as impediments to conversations with grantees and acknowledged this would not change overnight. Suggested strategies:

Engaging grantees in candid dialogue, listening, and responding. Grantmakers understand how important it is to know what grantees are thinking and the value of better understanding grantee realities. Many grantmakers are working very hard to create honest, open dialogue. Some are moving to “less paper” in reporting and increasing the time spent “face to face.” One grantmaker, new to the field, spoke of how critical candid dialogue with grantees is: “If a grantee sends a report that says 100 percent great news, call them back and say you don’t believe it. It is a disservice to us and our grantees if we are not totally candid about strengths as well as shortcomings.”

Valuable learning comes from challenges and failures. Grantmakers know that projects don’t go as often reported. “If we are authentic about being a learning organization, then we should provide resources that can help when a grantee runs into trouble. It is our responsibility as good grantmakers to help grantees feel comfortable enough to tell us that something imploded.”

Grantmakers can help grantees become more visible via marketing assistance. Southern California Grantmakers have developed an online calendar with GPS capability. “Not only does it promote grantees, but helps them generate income.”

Relationship-building beyond the money. “Open, candid dialogue with grantees is critical. We initially listen to their concerns and needs, and may share those concerns with others (grantees and grantmakers) when appropriate and useful. We then translate some of those needs to improve our grantmaking practices.”

Surveying. One foundation conducted a five-question survey of grantees across all departments to learn what grantees were thinking in response to changing scenarios.

Increasing site visits. “We learn far more by visiting an organization than we do from reading a report.” One grantmaker shared the surprise of learning about work force reductions only by visiting grantees. “Nothing in our reports told us just how over-extended paid staff was and, as a result of seeing realities first-hand, we are being more mindful of what we expect and what we request.”

Supporting sabbaticals. A few grantmakers are supporting reflection and renewal time, and provide sabbaticals for grantees.

Convenings of grantees. One grantmaker spoke of a conference of grantees after 15 years of annual funding “to gather feedback and discuss what we could do better to help grantees succeed.” “We can’t overstate the value of meeting the people and artists doing the work. Give them a safe space to talk about their needs, issues and what they face.”

PARTNERS AND ALLIES

The question, “Who are your partners in helping to ensure cultural sector success?” elicited 631 responses from 220 peer group participants, and it elicited marked differences in responses from types of grant makers.

Responses from corporate and foundation grantmakers (peer groups 1-5) constituted 53 percent of all responses. The balance of participants were national service groups; national, regional and state arts agencies; local arts agencies; nonprofit regranter and service providers; and, community foundations (peer groups 6-10.)

The most frequently listed partners by corporate and foundation funders (peer groups 1-5) included:

- Arts grantmakers or funders in their communities with the same priorities

- Academic institutions and universities for their research assistance

- Artists, experts and consultants in the field

Less frequently mentioned were:

- Business and thought leaders

- Community-based organizations

- Education systems

- Grantees

- Local arts agencies

The aggregate response from peer groups 6-10 read like a community profile. In addition to the above named partners of their colleagues in groups 1-5, their list included:

- Arts and non-arts community-based organizations

- Businesses and corporate leaders

- Chambers of commerce

- Civic leaders and civic organizations

- Departments, agencies, and elected officials in local, state and federal government

- Economic development entities, both public and private

- Entertainment sector and for arts for-profits

- Faith-based communities

- National, state, regional and local arts service organizations

- New immigrant communities

- Public and private academic institutions, pre-K through universities

- The full range of health and human service organizations

- The press

- New and social media

- The tourism industry

- Arts patrons

- The public-at-large

CONCLUSION

Many believe the recession may be the impetus for long-needed shifts in policy and practice. While it’s impossible to craft precise strategies to ensure the cultural sector will be thriving in 2020, no one is standing still. However, clear to everyone is that the greatest cultural sector success stories of 2020 will be of grantmakers and grantees with the will, energy, capacity and courage to adapt. Grantmakers and service providers of all sizes and structures are questioning every value, practice, service, and activity and working diligently to ensure they are doing the right things, with the resources they have, to produce the most effective results.

History says, Don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up

And hope and history rhyme.

So hope for a great sea change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that a further shore

Is reachable from here

Believe in miracles

And cures and healing wells.3

— Seamus Heaney

Notes

- Heifetz, Ronald, Alexander Grashow, and Marty Linsky. “ Leadership in a (Permanent) Crisis.” Harvard Business Review, July-August, 2009. http://hbr.org/2009/07/leadership-in-a-permanent-crisis/ar/1

- Hansen, Morten T. “When Internal Collaboration Is Bad for Your Company.” Harvard Business Review. April, 2009.

- Heaney, Seamus, trans. An excerpt from The Cure at Troy: A Version of Sophocles’ Philoctetes. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1991.