Allyship in Arts Grantmaking

For the past decade, landmark research has begun proving what many creatives have long known: the arts have an equity problem. And it is widespread. Despite cultural phenomena like the hit Broadway musical Hamilton, asymmetries are ubiquitous in the production and consumption of the arts.

Until recently, equity issues in the arts were largely anecdotal. Actors, directors, and audiences made claims about racism and sexism in productions without the backing of empirical evidence. As a result, their charges often went unsupported. But the arts landscape has changed. A combination of increased visibility and the widespread availability of research on social injustice has made the ubiquity of marginalization in the arts a preeminent concern for funders and creatives alike. The formation of the Asian American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC) is a prime example of this shift.

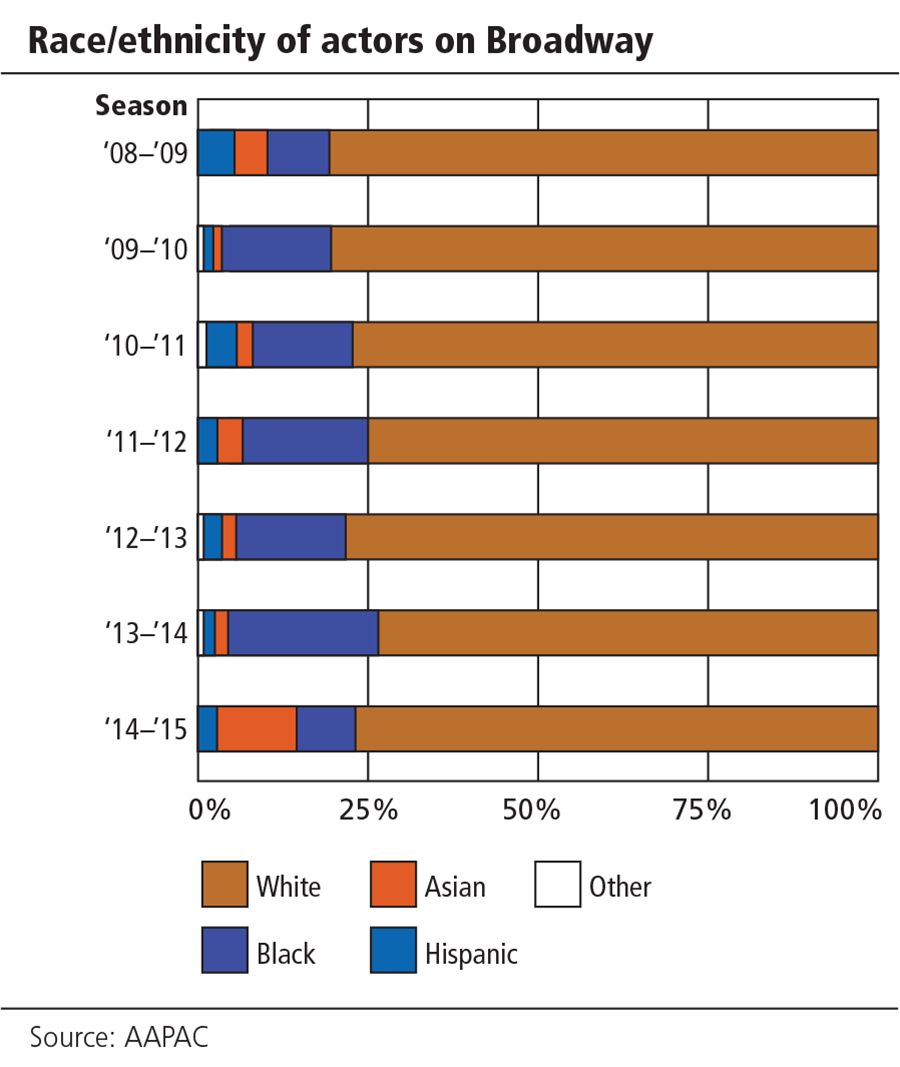

The AAPAC tracks racial demographics both on and off Broadway. It formed in 2011 after veteran actor Pun Bandhu found himself rejected for a role calling for an Asian American lead. After Bandhu lost the role, he sought support on Facebook, where he posted, “It just seems like things in theater are getting worse for Asian-Americans.” The status update received nearly four hundred comments and birthed the AAPAC.1 In 2016, the AAPAC found that white actors monopolized roles at a rate of 80 percent, a number that had remained consistent over the past seven seasons.2

Black Americans are in a distant second in the study, being cast in 20 percent of available roles in musical theater. The Pew Research Center estimates that by 2030, Latine and Asian Americans will comprise 22 percent and 6 percent of the country’s population, respectively. However, Asian, Latine, and all other people of color are cast both on and off Broadway at an abysmal rate of less than 5 percent per each demographic group. Musical theater is a snapshot of the arts more broadly. These kinds of disparities are prevalent in every other major genre. Whether in theater, visual, or cinematic arts, diversity is a glaring issue.3

Inequality in the arts is holistic. It exists at individual, interpersonal, and institutional levels. Grantmakers who are committed to seeing the arts thrive as an inclusive multiracial- and gender-expansive enterprise must pursue allyship at each of these levels.

An ally is someone who takes on a struggle for equity that is not their own or that of their community. Allies use their privilege and their power to center the people most impacted by inequity. Allyship is a lifelong process, one that involves both personal reflection and systemic action. In the context of the arts, allyship encompasses a spectrum of strategies.

Question Personal Beliefs

First and foremost, grantmakers must work to interrogate what kinds of projects they find themselves drawn to funding. Is interest in certain works and venues due to “like me” bias? In other words, do these projects remind us of ourselves as a dominant group? More importantly, funders should ask themselves why. Do affinities for specific projects involve assumptions about what “good” art looks and sounds like? Is there elitism when it comes to venue or subject matter? Do funder expectations mimic the Eurocentric and male-dominated norms common in most theaters and museums?

The arts have a checkered past. These traditional forms draw upon a lineage of Western European and masculine dominance, which accounts for many of the social asymmetries they replicate. American musical theater is no exception. It can be traced back to minstrel shows during the nineteenth century. White actors darkened their skin to play slaves, a practice known as “blackface.” When Black actors were finally integrated into these shows, social norms dictated they portray their community in degrading ways. While not all musical performances involved minstrelsy, according to the Cambridge History of American Theatre, it was “the chief frame within which some folk elements appeared in an organized element for paying spectators.” Yet, art that pays homage to the cultures of people of color is frequently siloed and unsupported.

White, Western lenses are the universal norm in much of the arts, but they are a minority in the world. Simultaneously, works that represent communities of color are often critiqued as too specific or irrelevant to wider audiences. Asking hard questions about what gets funded and for what reason is a foundational first step toward ensuring the arts reflect the world around them, because these seemingly innocuous personal beliefs translate into a shortage of support for creative ventures that trouble dominant perceptions of art.

A study by the Devos Institute at the University of Maryland found that arts organizations of color are much less financially secure and smaller than their mainstream counterparts. The median budget size of the twenty largest arts organizations of color surveyed in the study was more than 90 percent smaller than that of mainstream organizations. Moreover, arts organizations of color — specifically those that are African American and Latino — have fewer individual donors and are more reliant on grants from foundations and government sources. Funders have the power to shift the bleak portrait painted by these statistics. Questioning personal biases is vital; however, it is imperative to go beyond individual solutions. Racism, sexism, and ableism are structural realities that impact entire populations, and tackling them requires systemic measures. For grantmakers, the path toward equity is paved with creativity and thinking outside of the box. Grantmakers must fund community-driven projects and initiatives.

Fund Holistically

Centering impacted communities is a key feature of allyship. Supporting organizations geared toward communities of color will go a long way in altering financial precarity endemic in arts organizations of color. The Devos Institute study further found chronic financial deficits are common, making up at least 10 percent of the annual budget for many of the leading arts organizations of color they surveyed. For grantmakers, this translates into unconventional funding priorities. Grantmakers can allocate funding toward organizations that holistically focus on the communities they depict in their art. This means backing programs that both value diversity externally and are led by it internally. Tokenism — or pointing toward the hiring or position of one marginalized person as a way of proving a commitment to inclusion while not structurally supporting their community’s equity — is an all too familiar dynamic in the arts.4 Racial equity calls for something different: programs and productions that are staffed by the people who belong to the marginalized groups they portray. Theaters like Crowded Fire and Campo Santo, with executive directors and staffs of color, exemplify community engagement at all levels.5 Grantmaking should go beyond a fixation with the final product to consider who leads the process by which art is made. By funding culturally competent creatives to produce nuanced and powerful art, grantmakers can model the material and social value of racial, gender, and class diversity.

Importantly, funders should critically interrogate the kind of representation programs and initiatives offer and whether they portray marginalized communities in an honest, authentic, and whole manner. In other words, the type of art an arts organization of color produces matters. Black feminist scholar Patricia Hill Collins calls on society to shift away from the language of stereotypes and toward the concept of controlling images. She argues that controlling images naturalize oppression. The relationship between the social imagination of race and its material reality is easy to see.

In 2014, a Media Matters for America study of crime coverage in New York City found that every major network station disproportionately focused its crime coverage on Black suspects. This resulted in news broadcasts that exaggerated the proportion of Black people who were accused of crime by 24 percent. In the same city, 4.4 million police stops occurred between 2004 and 2012. In 83 percent of these cases, the person stopped was Black or Hispanic, even though the two groups accounted for just over half the population. Of the people stopped by the New York police, 94 percent were innocent. To mediate the impact of controlling imagery, funding applications must ask vital questions about not just whether people of color are depicted but how they are portrayed. Do people of color experience multidimensional realities? Are LGBTQ communities cast exclusively as villains? Do disabled characters have agency, or are they simply set dressing to be saved by their able-bodied counterparts? Even the most progressive media can fall prey to controlling imagery. Grantmakers can support comprehensive diversity in arts organizations by shifting beyond topical representation in order to glean whether the creative work being produced mirrors the complex everyday realities that marginalized communities experience.

Prioritizing projects that improve access to culturally relevant art is a critical part of full-spectrum diversity. We know that the arts have tremendous potential to impact those who need them the most. Research published by the University of Pennsylvania’s Social Impact of the Arts Project (SIAP) found that low-income New York City residents with more access to cultural resources experienced an 18 percent decrease in the serious crime rate, a 14 percent decrease in cases of child abuse and neglect, and an 18 percent increase in the rate of students who scored at the highest level on standardized tests.6 Yet, Broadway audiences are an overwhelmingly racially homogenous; 83 percent white. Questions funders can ask include the following: Are ticket prices cost prohibitive? Are tickets offered on a sliding scale based on need? Is the space reachable by public transportation? Does the production offer a welcoming environment for all audience members? Funders must consider both the content of an artistic message and how to ensure that those who would benefit most from it have access to it.

Build Inclusive Policy

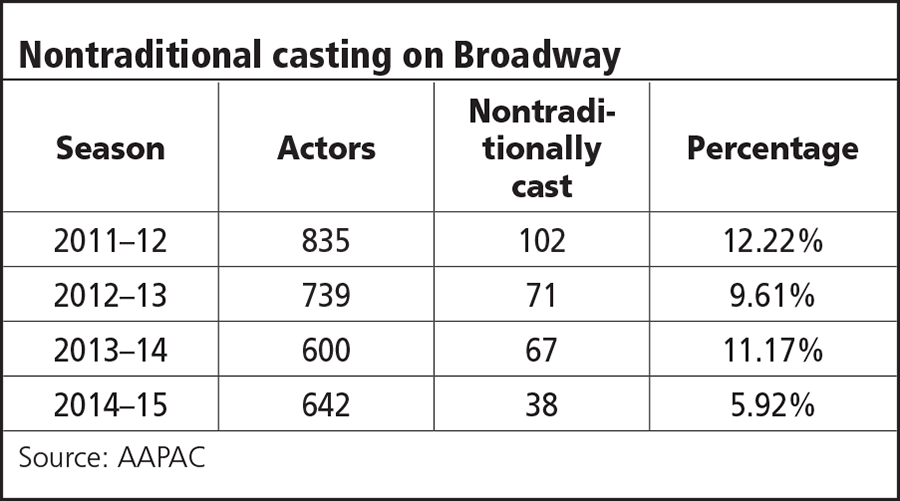

Racial equity, diversity, and inclusion are directly related to policy. The AAPAC statistics reveal the need for new protocols like nontraditional casting, a practice only 10 percent of theaters engage. The absence of support for policies like these are a driving force of racial disparities when it comes to who is on stage and in the audience.

Finally, grantmakers themselves need to implement equitable practices internally if they seek social change externally. A 2015 report on diversity in giving found that nearly three-fourths of donors are white, despite the fact that whites make up only 64 percent of the population. It further found that both African Americans and Hispanics are underrepresented in the donor universe. As a field, philanthropy is conspicuously racially monolithic. This means that allies within grantmaking must be proactive in reshaping philanthropy itself. A transition toward a multiracial, gender, and disability inclusive funding landscape goes hand in hand with diversity in grantmaking. Internal hiring emphasis should be given to those who would add to a new racially equitable philanthropic culture, not necessarily those who already fit within its narrow racial confines. Committing to organizations that fund nontraditional casting should accompany a robust focus on hiring nontraditional job candidates within philanthropic organizations — people who will bring new diversity- and inclusion-oriented lenses.

Lastly, philanthropy is largely unregulated.7 The wholesale absence of oversight in the industry means racial and gender asymmetries have been allowed to exist unabated. At a foundational level, allyship is a relationship of accountability to marginalized communities. For arts grantmakers, this relationship will require creating internal diversity initiatives that serve to balance a historically skewed power dynamic. The creation of board and staff subcommittees dedicated to racial and gender equity can go a long way toward arcing grantmaking in the direction of social justice.

Every day, new literature is published that challenges the existing paradigm of philanthropic giving. In October 2018, Edgar Villanueva published Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance. In the book he argues that philanthropy reproduces colonial structures, replicating racial hierarchies and social injustice. A few months later, New York Times columnist Anand Giridharadas published Winners Take All, a best-selling book challenging the paradigm of philanthropic giving as a self-aggrandizing and self-necessitating endeavor. These texts are layered over similar existing research. Together, they speak to a sea change within philanthropic giving, one that requires taking stock of who gives and why, and how funders and funding must change if equity is their goal.

Diversity- and inclusion-driven policies are proven strategies. Nontraditional casting is a part of what made Hamilton such a widespread success. The promotion of Misty Copeland to be the first Black American principal dancer for the American Ballet Theatre rejuvenated audiences and brought new life to ABT.8 But incentives for equity surpass profits. The phrase “art for art’s sake” glosses over a multitude of sins, many having to do with race, gender, and class. The prevalent research findings on racial and gender inequity in theater, visual, and cinematic arts are cause for concern. More importantly, they are a call to action. For grantmakers, artists, and audiences, the time has come to question and address inequity in the arts.

Kim Tran is an anti-oppression consultant and author who uses a grassroots organizing and transformative justice approach. Her clients include Stanford University, the United States Foreign Service, and the Open Society Foundations. She is currently writing a book titled The End of Allyship: A New Era of Solidarity.

NOTES

- Asian American Performers Action Coalition, “Ethnic Representation on New York City Stages, 2016–2017,” http://www.aapacnyc.org/uploads/1/1/9/4/11949532/aapac_2016-2017_report.pdf.

- Mimi Onuoha, “Broadway Won’t Document Its Dramatic Race Problem, So a Group of Actors Spent Five Years Quietly Gathering This Data Themselves,” Quartz, December 4, 2016, https://qz.com/842610/broadways-race-problem-is-unmasked-by-data-but-the-theater-industry-is-still-stuck-in-neutral/.

- “Looking at Hiring Biases by the Numbers,” Equity News, 102, no. 2 (Spring 2017): 9–18, https://www.actorsequity.org/news/EquityNews/Spring2017/en_02_2017.pdf#page=5; Roger Schonfeld and Mariët Westermann, “The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation: Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, 2015, https://mellon.org/media/filer_public/ba/99/ba99e53a-48d5-4038-80e1-66f9ba1c020e/awmf_museum_diversity_report_aamd_7-28-15.pdf; April Reign, “#OscarsSoWhite Is Still Relevant This Year,” Vanity Fair, March 2, 2018, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2018/03/oscarssowhite-is-still-relevant-this-year.

- Early in 2019, former American Conservatory Theater faculty member Stephen Buescher filed a lawsuit against the theater company for racial discrimination. Lily Janiak, “Former ACT Faculty Member Sues Theater Company for Racial Discrimination,” Datebook, February 19, 2019, https://datebook.sfchronicle.com/theater/former-act-faculty-member-sues-theater-company-for-racial-discrimination.

- Crowded Fire Theater: http://www.crowdedfire.org/; Campo Santo: https://camposantosf.tumblr.com.

- SPS News, “New Research Shows How Arts and Culture Improve Health, Safety and Well-Being,” March 9, 2017, https://www.sp2.upenn.edu/new-research-shows-arts-culture-improve-health-safety-well.

- In 2015, the New York Times published an opinion piece by David Callahan, “Who Will Watch the Charities?” asking critical questions about the lack of transparency and accountability in the philanthropic sector, noting, “Philanthropy, we’re learning, is a world with too much secrecy and too little oversight. Despite its increasing role in American society, from education to the arts to the media, perhaps no sector is less accountable to outsiders”; https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/31/opinion/sunday/who-will-watch-the-charities.html.

- Ruth La Ferla, “The Rise and Rise of Misty Copeland,” New York Times, December 18, 1915, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/20/fashion/the-rise-and-rise-of-misty-copeland.html.