Too Many Elephants in the Room to Count: When a Conversation on Affordable Housing for Artists Refuses to Address Reality

Affordable housing for artists.

This topic is a hard one for me. I’m too invested. I know too much. I have had too many people close to me lose their housing and simultaneously, lose the place where they create art. For one of my friends, when he lost his home and his space to create art, he not long after, lost his life. Colin Ward, a fixture of Denver’s Do-It-Yourself arts community, died by suicide on February 1st, 2018, fourteen months after he was evicted from his home, the internationally-recognized art space, Rhinoceropolis. After the surprise eviction, Colin’s life was never the same; many of us close to him saw a direct connection between his displacement and his death.

Colin was one of dozens of artists—and one of thousands of people—in Denver to lose their homes and work spaces to surprise/unwarranted evictions, rising rents, unfair housing practices, and handshake leases that evaporated once land values skyrocketed. Predatory and classist real estate deals, often occurring in celebrated “arts districts,” have systematically removed artists from Denver’s many neighborhoods.

When I saw the conference workshop Innovations in Artist Housing: Inspiration from South America to address the “Soho Effect”, I was stoked. I thought, based on the other conversations and panels I had witnessed so far at the GIA conference, I was sure to learn something from one of many experts. Maybe I would hear from an artist in another city who overcame the housing challenge in a way I had not thought of before. Or, maybe there would be a real estate developer interested in talking about the real causes of rising affordability and what communities can do to stabilize themselves and prevent displacement. Maybe, just maybe, there could be talk of what homelessness, mental health and art have to do with each other, and the role stable housing can play in an artist’s quality of life.

As I was walking into the panel’s location, Redline—the gallery/studios/community space located right in the heart of Denver’s many social and homelessness services—I saw two friends walk in the building ahead of me—two artists who I had worked alongside during the mass evictions of artists and art spaces in 2016. (A knee-jerk reaction many cities across the country had to Oakland’s heartbreakingly deadly Ghost Ship Fire.) These artist friends of mine were people who had gone to city council meetings to implore city officials to do something—anything—about the crisis; they were people who had spent long nights strategizing around the legal rights of artists; they were artists who spent hours researching fair housing laws and real estate transactions along Brighton Boulevard, the strip of the city that is, on paper, an “arts district,” but has been the epicenter of visible artist displacement. I was hopeful; maybe my friends were joining the conversation, allowing conference goers from around the U.S. to hear firsthand from artists living through an affordability crisis in Denver.

But the presence of my artist friends at Redline was merely a coincidence. The panel on artist housing did not include a single artist, let alone an artist impacted by—or blamed for—the “SoHo Effect.” Instead, the panel physically resembled many urban planning panels I’ve had to painfully sit through—upper middle class white people who want to talk about housing, mostly in terms of real estate values and sexy urban design. They did not want to talk about the realities just outside the windows of the room I began to feel trapped in.

Most disappointing were comments from local developer Mark Falcone. His story was one I’ve heard over and over in the world of development and real estate investment—a wealthy guy who came up in the New Urbanism movement of the 80s and 90s, a time when “center city” infill was going to be the savior and the suburbs were to be scoffed and shamed (even though many of us Gen Xers and Millennials grew up in these so-called bastions of bland, because our parents bought houses in the suburbs—generational results of white flight and/or sometimes because the burbs were affordable, etc.) He showed us lots of renderings and photos of big, shiny object projects he had worked on, talked big game about the rise in an interest to “move back to center cities” (as if there weren’t people—mostly black and brown folks—living there all along,) and on and on. Downtowns are like, revitalized now, everyone.

I am a privileged, housing-stable artist who has spent countless hours trying to get to the bottom of my city’s current housing crisis. Because of this, I have been privy to dozens of conversations in rooms where mostly white men with generational wealth get to talk about “building cities” without any mention of their own privilege, the impacts of land value and who decides its value, their role in land speculation and what it does to communities, what historically racist housing and land policy did/does to generations of families and their rising inability to grab ahold of that mythical concept of home equity, how gentrification is systematic and not elusive, and so on.

One of the most popular (and tired) tropes in this great game of hot potato known as “who’s fault is gentrification?,” is that artists are to blame. But, in this progressive space and in this progressive conference looking at money in art, I did not expect the “artists start gentrification” line to be uttered by a developer who has played a crucial role in the land acquisition (and gifting of that land,) to our modern art museum, not to mention partially funding and building said museum. To more accurately quote Falcone, artists are “the tip of the spear” of gentrification. The developer-favored assertion that artists are to blame for existing is very convenient, as it serves to distance real estate investors from the truth: artists almost never own the land they live on. They aren’t the ones buying up huge swaths of lower income communities in a gold rush-like speculative fashion. They aren’t the ones who have relationships with politically-adjacent powers-that-be who make these land acquisitions super easy. And artists certainly aren’t the ones out here re-naming neighborhoods in an effort to sell a lower-income communities out from under peoples’ grandmas.

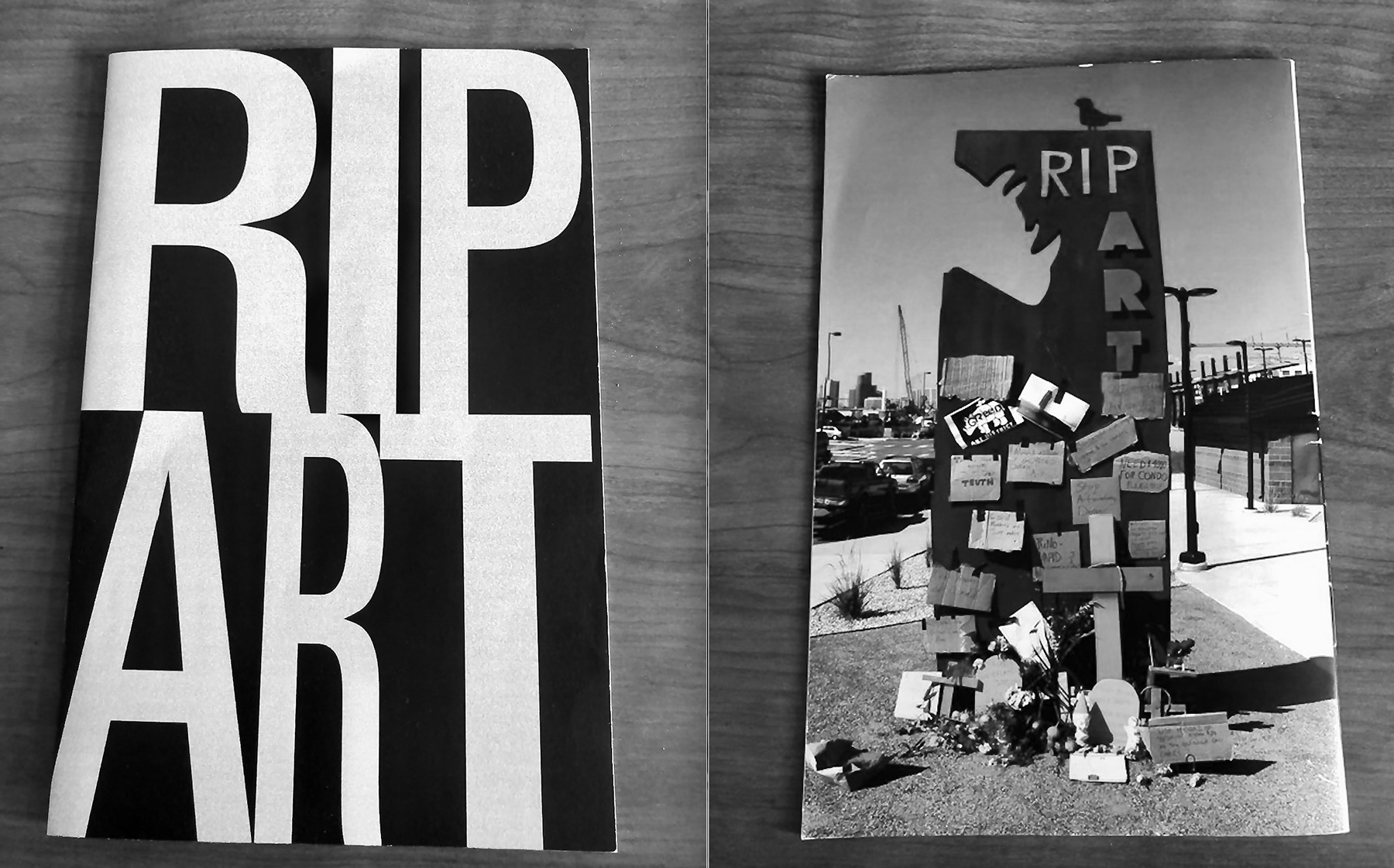

This is not to remove artists—and in this context, I mean mostly white artists—from their role in how cities change, not always for the better. My artist friends Luke and Trevor who once lived at Rhinoceropolis, created a zine called RIP Art (which is not available online, but I did photograph it and post it, page by page on twitter, where you can read it.) It is the best takedown/breakdown of the artist’s role in gentrification that I’ve ever read.

At one point, Falcone said that in Denver, rents/housing consume “only 26% of a household income in Denver” and that people in his very office have proclaimed that they think they could squeeze Denver folks even harder and that the percentage of a person’s income going to housing “could be 32% in no time.” I was grateful and audibly relieved when another skeptical conference attendee commented that this was just the “planation mentality” in action, as the elites with power and land decide how the rest of the people “below” them live. Another conference attendee asked Falcone about some of the imagery in his presentation — alongside a bunch of statistics just how messed up housing issues are, Falcone used a photo of a tent city, an increasingly common sight in cities like Denver, where our community members experiencing homelessness often live. I didn’t catch a straightforward answer from the developer — but he seemed to brush off that part of our community’s life or death issue to talk about the “missing middle,” a part of the housing crisis urban planner professionals like to obsess over.

Just outside the door of this panel, in another studio space across the gallery at Redline, there was a gathering—it was a group of artists, many of whom are experiencing homelessness, working on their art. Redline is one of the few institutions in this city that is part of this “billion dollar economic arts boom” that actually works with artists at every level of their career, regardless of where they land on the economic spectrum. Housed or not, artists have a place at Redline. I wish this panel had made a place for these artists, too.