Impact Investing 101

Many foundations are considering adding impact investing as a tool to complement their grantmaking activities. This article explains the practice generally and as it applies to funders working in the arts and culture sector. We will begin by introducing the terminology and motivation for impact investing, then provide an overview of the options, and conclude with examples from four foundations that have made impact investments in arts and culture.

Understanding the Language

The term impact investing covers all investments that seek both financial return and social/environmental impact. Some private foundations prefer terms like mission investing or mission-related investing. At Philanthropy Northwest, a six-state network of foundations, philanthropic funds, and corporate giving programs, we simply use impact investing as the umbrella term.

Impact investments can be made throughout the asset classifications common to endowments. A common type, unique to private foundations, is the program-related investment (PRI) of debt or equity in a for-profit or nonprofit entity. Motivated chiefly by the mission impacts they create, PRIs are made with the explicit expectation that they will earn below-market financial returns. Based on Internal Revenue Service criteria, PRIs can apply toward a private foundation’s annual charitable payout, which means they are counted as grants and booked as charitable assets.

Some private foundations make investments that would qualify as PRIs directly from the endowment portfolio and do not count them as PRIs. They may not want to “cut into” their grant budgets to do impact investing. Or their strategy may simply have built both market-rate and below-market investing into endowment financial planning. This is acceptable. However, some conventional financial advisors will not “cover” below-market investments as part of their managed portfolio.

Philanthropic investment opportunities in community arts and culture would usually offer below-market financial returns. That means that arts funders are likely to face the decision whether to make a PRI if they decide to adopt an impact-investing strategy.

Why Adopt Impact Investing?

The first step in any exploration of impact investing is to drill down to the fundamental reason for adopting the strategy. This requires a conversation with trustees and staff about how the foundation exists as a mission-oriented entity, both in the financial market and in the community.

Some trustees will be more focused on whether the investments in the traditional endowment are aligned with the foundation’s mission. Does the endowment itself support or undermine the foundation’s work? They no longer consider the endowment “mission neutral,” and they want to consider the environmental and social impacts of the foundation’s investments.

Other trustees focus more on the program side of the foundation. They are interested in the environmental and social impacts to be gained by working on the “business” side of their communities. Perhaps investing could be added to grantmaking activities to achieve greater impact?

Most foundations have some blend of both these motivations and interests, and it is helpful to tease out which are most important to trustees and staff. We find that impact investing touches leadership’s bedrock beliefs about a foundation’s purpose and function. The beliefs are shifting, and everyone involved needs room to learn, consider, and move forward with shared understanding.

This stage of thinking, with careful attention to core motivation, often yields a set of initial parameters for exploring impact investing. The foundation may be expansive, looking at the entire endowment to see all the options for leveraging assets toward the mission. Or it may zero in on certain investing themes because of its own closely drawn mission.

What Are the Options?

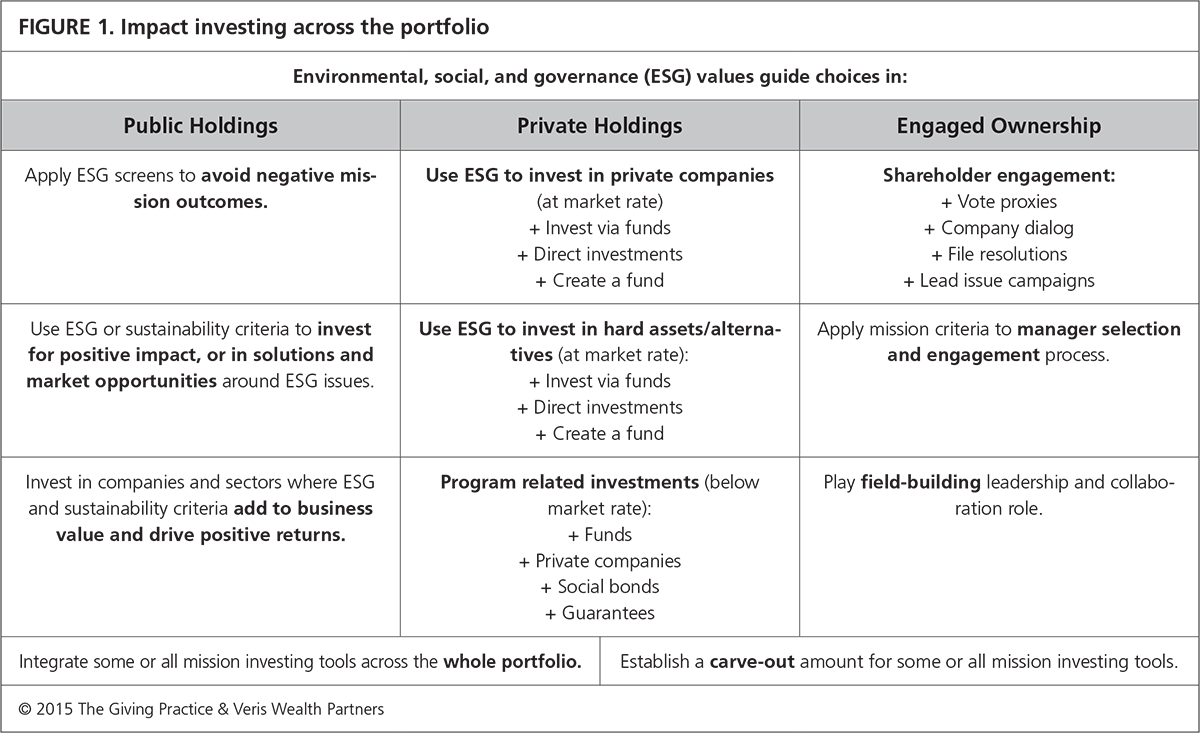

Once a foundation has established its priority motivations, leadership can begin to assess the options. Theoretically, impact investing opportunities are available in every asset classification (see figure 1). But in practice, the majority of impact investments that directly involve arts and culture are in the private holdings asset classification.

The Giving Practice, Philanthropy Northwest’s consulting team, and Veris Wealth Partners have completed a national scan of potential impact investments relating to arts and culture for private foundations. We found no public holdings and few private equity funds that created significant impact in the arts and culture sector. Most opportunities involved direct investment in arts and culture companies, projects, and funds, all with below-market returns; most could be considered for PRI classification.

The most common impact-investing opportunities in the arts and culture sector involve financing real estate or relevant businesses. Both can help support job creation, stronger communities, and a vibrant arts and culture climate.

1. Financing Arts and Culture Real Estate

Impact investors can provide inexpensive debt as part of the overall financing plan for a museum, studio, theater, or other arts-related building. The borrower is often a nonprofit organization. This kind of real estate investment is often the first impact investment a foundation pursues. The opportunity may arise because a trusted grantee is ready to buy a building. The foundation is probably familiar with the financial health of the grantee, as well as its track record bringing arts and culture to the community. Willingness to “try something new” is higher when working with a known borrower.

Another real estate opportunity could be to finance a building for a company that employs artists and creative professionals. This could even be a for-profit company with design workers, and it may amplify positive social impact by training and recruiting residents of a particular neighborhood or by increasing opportunities for women or people of color.

When investing in real estate, a foundation evaluates the loan by examining the value of the building to be purchased, and the historical income and expenses of the borrower. This is a relatively straightforward underwriting, and many foundations have existing board members or staff who are already comfortable with this process.

A larger and more complex real estate opportunity could be to help finance the development of arts-oriented commercial or mixed-use buildings or neighborhoods. In this case, the new buildings could offer work and show space for artists and creatives, possibly along with affordable housing that is attractive to these workers. Typically — but not always — developers seek below-market financing from foundations for this type of project. The investment could be in the form of debt or the purchase of an equity share in the projects. Amounts are larger, and involvement of attorneys and specialists is probably required. The payoff, however, is large in the form of permanent real estate designed specifically to raise the arts and culture profile of communities.

2. Financing Arts and Culture Businesses

Foundations can also support arts and culture with favorable financing for businesses, usually in the form of a small-business loan or microloan, and sometimes with equity financing (buying an ownership share). Typically, these investments offer below-market financial returns.

Arts and culture business investments might go to visual, performing, and literary artists. Some foundations also target businesses that employ creative professionals working in technology and other design-heavy sectors. Still other foundations focus on nonprofits that offer arts and cultural programing in the community.

When a foundation creates a fund to provide loans or equity financing, it may need to develop significant new capacities. Investing requires systems for underwriting, deal structuring and closing, and investment maintenance. To avoid the costs of building these functions, foundations could opt to invest with an intermediary that already has a fund to finance arts and culture businesses. These funds are often housed at community development financial institutions (CDFIs). There are more than a thousand of these lending organizations around the country today, including sixty-eight in the Northwest, focused on financing social benefits for communities.

One caveat: financing for artists and creatives is usually just one part of what the intermediary does. It is somewhat rare to see a dedicated arts-financing fund. However, even if the financing is folded into a larger fund, the intermediary may offer specialized support to artists and creatives. A foundation could fund these supporting services with grants, too.

Getting Started

As noted earlier, the first step in the process of exploring impact investing is for trustees and staff to clarify their strongest motivations. This conversation will flesh out how strongly and under what conditions leadership is ready to explore using foundation assets in new ways in service of the mission.

The foundation can then explore whether to take small, large, or no steps toward impact investing. It is helpful at this point to scan impact investments that meet the foundation’s situation. The opportunities will vary depending on the size and flexibility of the endowment, the mission goals that are important to the foundation, and the availability of investments.

Looking at “live” examples often guides staff and trustees directly to the right path for impact investing. They help the foundation make a concrete assessment of all the important variables: the amount of money required; the possible returns, both impact and financial; and the new capacities that might be required. With this information in hand, the foundation can devise initial steps for impact investing and set a timeline for continued learning and exploration as the strategy unfolds.

Examples

Bonfils-Stanton Foundation

Bonfils-Stanton Foundation made a PRI in the amount of $1 million to the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) Denver that contributed to a larger restructuring of the outstanding bank liability carried by the museum. The final key component of a capital campaign and debt restructuring that began in 2012, the PRI placed the museum in a much stronger financial position by enabling it to reduce $11.8 million in bank debt to $2.7 million remaining in bank debt (at a reduced interest rate) and $3 million in PRI below-market loans, while also freeing up roughly $460,000 in funds that would have been used for debt service. The foundation’s PRI, which is combined with like PRIs from a few other private donors, is structured as a loan, with a below-market interest rate and interest only for the first five years of the amortization period. The MCA will reinvest those savings in the organization by strengthening its infrastructure, increasing its reach in the community, and connecting wider audiences to their exhibits and programs, positioning them for strength in the future. Bonfils-Stanton Foundation was able to make a much larger PRI loan than it would have been comfortable making as a single annual grant to a single institution.

HRK Foundation

In 2006, HRK Foundation initiated a partnership with the Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) to support its goal to acquire and conserve historically significant objects that enhance the museum’s existing collections. Through the Art and Martha Kaemmer Fund, the foundation extended a $100,000 revolving line of credit to the MNHS. After potential acquisitions are approved by the museum’s accessions committee, MNHS requests a loan from the foundation. HRK Foundation disburses the loan to the MNHS in increments of $10,000 or more via wire transfer within three business days. The museum submits a repayment/fundraising plan within thirty days. The investment earns the foundation 2 percent interest and helps the community-based museum acquire and restore historical artifacts to promote education and engagement with local history. At least once a year during the existence of the PRI loan, the MNHS is required to submit a complete annual report documenting how the PRI loan was spent. Collections acquired through the HRK Foundation loan program include a rare first German edition of Father Hennepin’s Beschreibung der Lanschafft Louisiana, an important account of the first European to see what is now Minnesota; and the Alexander G. Huggins Diary and Family Photographs, a collection of family diaries, photographs, and albums that document nineteenth-century Dakota mission life.

Northern California Grantmakers

Administered by members of Northern California Grantmakers, the Arts Loan Fund (ALF) has provided quick-turnaround, low-cost financial assistance to arts organizations located in the San Francisco Bay Area since 1981. ALF loans range in size from $10,000 to $50,000 and encompass production support for galas and public performances to opportunity loans that help arts organizations develop new revenue streams or cost-saving opportunities. ALF also provides bridge loans intended to help small organizations with urgent cash-flow needs, and smaller loan products, like quick qualifier loans of up to $10,000, to those who have previously applied and have repaid their loans on time. The fund offers several application deadlines throughout the year, and steering committee members review applications on a six-week cycle, dispersing funds immediately after loan approval. Considered low-risk at a 2.25 percent interest rate, loans must be repaid within one to twenty-four months, depending on the loan product and the confirmed source of income for repayment. To date, ALF has provided 1,345 loans totaling $18,679,581, a significant investment in the health of the Bay Area arts community.

ALF loans have supported several arts and arts education programs throughout Northern California, concentrating on many organizations in Oakland, San Francisco, and San Jose. Root Division, a visual art nonprofit that connects creativity and community through a dynamic ecosystem of arts education, exhibitions, and studios, secured a ten-year lease in San Francisco’s Central Market District after having been displaced from the Mission, unfortunately a common trend affecting many arts and nonprofit organizations in the Bay Area. Root Division was successful in launching a successful capital campaign, earning a Creative Space Grant by the San Francisco Arts Commission and procuring resources, including pro bono architects and designers, to develop the new facility. However, additional funding was needed to manage operations at this critical juncture, and sources were not immediately available. The ALF provided an opportunity for quick access to funds through its bridge loan program. With ALF assistance, the organization was able to move forward on designing a new facility that will house multiple classrooms, exhibition spaces, a digital lab, and workshop space as well as provide twenty-two subsidized artist studios at below-market costs.

Rasmuson Foundation

In 2013, Rasmuson Foundation worked with Cook Inlet Tribal Council (CITC) to structure an investment with CITC as the nonprofit sponsor of a special video-gaming initiative focused on developing a portfolio of game-infused learning programs that include Never Alone (Kisima Ingitchuna). The initiative generates new, unrestricted revenue that can be flowed back to CITC core social service programs while also reinforcing the organization’s commitment to cultural engagement and social justice. Initially, CITC approached the foundation with a request to make an equity investment directly in its indigenous-owned gaming company. Rasmuson wanted to share risk with CITC by participating on equal footing, which led the foundation to structure a recoverable grant with equity-like provisions for use of proceeds, profit sharing, return of capital, and preferred distribution of returns. The $1 million investment involves a fifty-fifty split on profits until the foundation’s initial investment is repaid, with an additional 5 percent return paid out over time. The PRI’s structure reflected Rasmuson’s relationship-based grantmaking approach and social investing philosophy and also allowed the funder to shape CITC’s business plan by expanding their target home consumer to educational consumers. The foundation requested the creation of a curriculum guide that could enable educators to use the game in classroom settings and also align with standards and measurable educational outcomes. Rasmuson’s investment in CITC created leveraging opportunities that also attracted additional investors while sharing in the risk.