Racial Equity in Arts Philanthropy

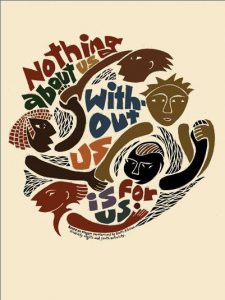

“Nothing about us without us is for us.”

This proverb, popularized by South African disability and youth activists, served as the introductory frame for the daylong precon, Racial Equity in Arts Philanthropy. These words were presented by facilitators as a challenge to the ways in which institutions may approach racial equity. (Think, colonialism. Think, the opposite of liberatory practices.) It set the tone outright for a conversation and exploration of racial inequity in art philanthropy that is at once structural and foundational to how a nation built upon racialized capitalism, i.e., genocide and slavery, operates.

So then, what is the real opportunity for racial equity within this context? The answer to that question is fundamentally rooted in both understanding the historic and persistent role arts philanthropy plays in maintaining racial inequity, and actively working to dismantle the racism rampant within and perpetrated by the field – by shifting power (money, resources, etc.) to ALAANA communities. A mouthful, I know. I’ll let these words by the wonderfully smart and funny Vu Le (Nonprofit AF) state it more succinctly.

“Equity is about ensuring the communities most affected by injustice get the most money to lead in the fight to address that injustice, and if that means we break the rules to make that happen, then that’s what we do.”

How does one break the rules? When asked this question, session participants were hard-pressed to come up with clear examples of how to share, let alone cede, power to those outside of our institutions. This is otherwise known as taking theory and putting it into ideas for practice. Sure. We understand that diversity and inclusion are not about examining power; and, inequity without the racial part is at best confusing, and at worst well, racist. But, moving from conceptual notions and understandings towards action that leads to institutional and structural change is another story.

Let me pause here for a moment. I use the terminology “we” in order to implicate myself as someone working in a local arts agency, who is accountable to the public, and to the City’s racial equity priorities. Additionally, my lived experience as a queer cisgender Black woman who works to be authentically accountable to community in my work and personal life troubles this paradigm at all times.

Who are you accountable to? Who is your organization accountable to?

It’s helpful to first consider what implicit and explicit racism look like in arts philanthropy. In a room mixed with woke folks, and others on the journey, the list we came up with included ways in which the sector invests in organizations with racial equity statements and policies, but little practice compared to the lived experience of ALAANA organizations, and white culturally specific institutions who are considered too big to fail. Funding organizations who question the validity of people of color focused funding programs as discriminatory, the requirement of a certified audit, 501c3 status, and data from applicants surfaced as other examples of how structural racism plays out in this work. A poignant illustration was made about culture in that often times relational decisions can define the nature of relationships between dominant culture organizations and funders, while ALAANA organizations are expected to just follow the rules. Studies were also referenced that show how boards of trustees of major foundations are primarily white men with Ivy League degrees. And, when considering arts funding within the context of race, we need only look to Not Just Money: Equity in Arts Philanthropy (Helicon Collaborative report from 2017) to see that despite the conversation about the need for racial equity, things are worsening. Root causes to racial injustice within the field are not fully being addressed.

Culture creates policy. Policy shapes racial outcomes.

The work for change lies in how we can and are responding to racism and white supremacy culture. Where do we choose to push and not push? Why? A litany of ideas arose that reflect efforts of staff-led organizing including, workers engaging in racial affinity groups to build allyship and solidarity to push against normative power structures alive and well in the sector. We must also lead with accountability to community. A case study presented by Philly’s Leeway Foundation that funds women, trans and gender non-conforming artists, urged participants to develop relationships with those most impacted by structural racism. Their leadership must be reflecting in the doing of how we do. Always.

Our session facilitators, whose efforts reflect a deep commitment to the work of justice summed up the responsibility of our racial equity work as follows:

- Training on structural racism is important to build common vocabulary and perspective

- Language matters

- Community involvement matters

- Cultural change and perception takes time

- Be patient and adjust as you go

- Take action from where you are – don’t wait for perfection

Our marching orders are clear. Do the work. And, keep doing it.