Race & Place

The GIA Conference is the best convening you’ve likely never heard of, unless of course, you work in grantmaking – which is a lot of people. I became aware of GIA and the conference when I began working for the City of Seattle Office of Arts & Culture in 2013. We are an office that in addition to public art programming and arts education, provides public funding for individual artists, community organizations, and cultural institutions. Our cultural partnerships programs – grants and more, have been a catalyst for stewarding racial equity in the office, as both internal practice and community engagement.

Today, I had the opportunity to attend a session highlighting the work of cultural partnership in Montgomery, Alabama entitled, “Creative Placemaking in the Racialized South.” Reading the session description, I was drawn in by two things: one, the focus on Black community; two, the description of geography within the context of race. I wanted to get a sense for what the emphasis on social identity and place is yielding in a region that is as Black as it is White. (I am Black, and live in Seattle where the population of Black people is 8%.)

There’s a line in Ava DuVernay’s newly released documentary, 13th (which puts front and center the devastating intersection of racial inequality and mass incarceration in the United States) that came to mind as I made my way to the session. It goes, “There is really no understanding of our American political culture without race at the center of it.” It follows, that conversations surrounding creative place-making, as it implies neighborhood (re)development, must also provide a context of race, and specifically the impact of racism on communities of color. And, that’s exactly what today’s session did.

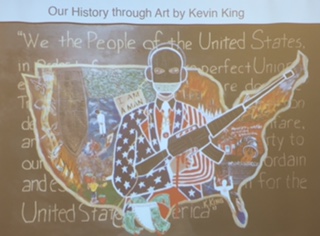

Kevin King, artist and Five Points Cultural Commission board member, provided a framework of the racialized south as foundational to understanding the approach to neighborhood revitalization in Montgomery’s Five Points area: “Certain major US periods have drastically shaped and continue to steer the direction of the economic realities of Blacks.” The US economy was rooted in slavery as an institution; post-Civil War emancipation and Reconstruction ushered in a backlash of racial terror, aka Jim Crow laws. That history persists as present-day disinvestment in Black communities in Montgomery, alongside a strong legacy of Civil Rights Movement.

The Commission and key partners, with support from ArtPlace, are leading the development of an arts and cultural district in Five Points. Artists, residents, and community members are key participants, serve as advisory members and implementers of this effort. The desire is to combat racial, economic and cultural displacement (or gentrification) as the area develops. Chase Fisher, the Commission’s president, spoke about this as an opportunity for communities to come together and break down barriers. “In transforming a place, you can transform people.”

A set of core beliefs guide the work, and community development agreements hold tenants accountable:

- Low income neighborhoods have the capacity & buying power to support businesses.

- Properties in low income neighborhoods can generate competitive returns.

- Low income neighborhoods are deserving of investment and good quality of life.

- Residents should have a voice. Community development should benefit the community.

- Arts & culture are essential component to thriving neighborhoods.

The project is faced with challenges that include a funding dynamic that equates to limited access in the deep south, local municipal resistance, and the historical and present reality of racial barriers. But, what I find hopeful is Kevin and Chase’s candor with one another about the way power moves, their creativity and racial analysis, commitment with community, and authentic collaboration. And they’re not afraid of the mistakes to surely come in such an incredible undertaking.