Democratizing Education: Democratizing Leadership?

Today anyone with an Internet connection can access thousands of courses online for free. With the rapid rise of these MOOCs (massive open online courses), the major disruption of our education system has been a hot topic of late. But democratizing education is not a new idea.

“It was designed to largely benefit those at the bottom of the ladder who want to climb up, or those who have some ambition to rise in the world but are without the means to seek far from home a higher standard of culture.” This quote comes from Justin Smith Morrill in a speech to the US Senate about the Morrill Act of 1862, a piece of legislation that allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges. It may have been 150 years ago, but the key principles involved — accessibility and practicality — continue to influence our approach to higher education in the United States.

Now, increasingly affordable technology is pushing more and more knowledge into consumers’ reach. In the arts and culture sector we have seen and often discussed the effect that this easily accessed information is having on audiences and patrons. What about leaders in the arts? Might the proliferation of online education affect the leadership of arts and culture organizations?

First, how did we get here? In 2008 University of Manitoba professors Stephen Downes and George Siemens coined the term MOOC to describe their course that explored the interactions between a variety of students through online tools. Twenty-five students attended the course on campus, and an additional 2,300 from around the world participated online.

In 2011, Stanford University offered three free courses online. Peter Norvig and Sebastian Thrun offered an artificial intelligence course to an initial enrollment of over 160,000 students from around the world, 20,000 of whom completed the course.

Thrun founded a company called Udacity in 2012, which began to develop and offer MOOCs for free. Later that year, Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller, two other Stanford professors, started a company called Coursera, which partnered with universities to prepare and offer MOOCs.

MIT developed the MITx platform for delivering MOOCs, which was renamed edX after a partnership with Harvard was formed. The nonprofit edX consortium, which develops and offers MOOCs, now has over thirty university partners.

More than four million students have enrolled for Coursera MOOCs. Both Udacity and edX have enrolled over a million students in their MOOCs.

Research on the effectiveness of MOOCs is fairly nascent, and there are many yardsticks by which success is being measured. A 2013 study by the University of Pennsylvania looked at one million students enrolled in Penn’s Coursera courses. According to the research, only about half of those who registered even looked at a lecture, and an average of 4 percent of enrollees complete the courses.1 It does not sound like much until you consider the scale. Forty thousand students completed those courses in a single year.

Last year Harvard and MIT researchers wrote a paper analyzing the first year of those institutions’ online platforms: HarvardX and MITx. Their conclusion, interestingly, was that “open online courses are neither useless nor the salvation of higher-education.”2

But what if we used Morrill’s yardstick? Are MOOCs accessible? Are they practical?

Accessibility is one area in which the metrics are fairly clear. The data, however, are not always there. Last year Harvard conducted a study of the socioeconomic status of its HarvardX learners. The researchers noted that “one of the challenges of conducting studies on how students from different background engage differently with MOOCs is that the desire to keep MOOCs easily accessible often precludes asking probing demographic questions as a condition of entry into a course.”3 As a result, researchers looked at where learners were located and cross-referenced that information with neighborhood data on household income and average education levels. While their study found that students indeed represented a wide variety of socioeconomic backgrounds, they were disproportionately individuals already advantaged in terms of resources.

In 2013, the University of Pennsylvania surveyed 35,000 of its MOOC users from around the world. The research showed that 80 percent of those students already have an advanced degree. In Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa, 80 percent of MOOC students came from the richest 6 percent of the population.4

Simply putting something online and making it free does not necessarily mean it is accessible. To take advantage of MOOCs, students must have access to a computer or mobile device with a reliable high-speed Internet connection. This can be a significant barrier to entry for some. And for those who can overcome this barrier, access does not always lead to usage. There is still a “digital divide” in the United States. Recent census data show that only 60 percent of African American households, 66 percent of Hispanic households, and 63 percent of rural households have broadband Internet at home.5 Compare that to 76 percent of white households, 86 percent of Asian American households, and 75 percent of urban households with broadband access.

What if we asked students about their own metrics? Why are they signing up? Additional Penn research found that 44 percent of their MOOC students enrolled in a course to “gain skills to do my job better.”6 Practicality.

In conversation, leaders at Khan Academy talk about students — whether children or adults — using their lessons as a safe place to practice or prepare. Many brush up on subjects online before taking an entrance exam or enrolling in a degree program. Udacity’s cofounder Sebastian Thrun talks about MOOCs as vocational training. Increasingly IT workers and other budding professionals are using MOOCs to build a portfolio or advance their skills.

What about the arts and culture sector? How might online education affect the way our leaders are trained? If we are looking at the impact on management and leadership in the arts, we have to look at the current path to leadership.

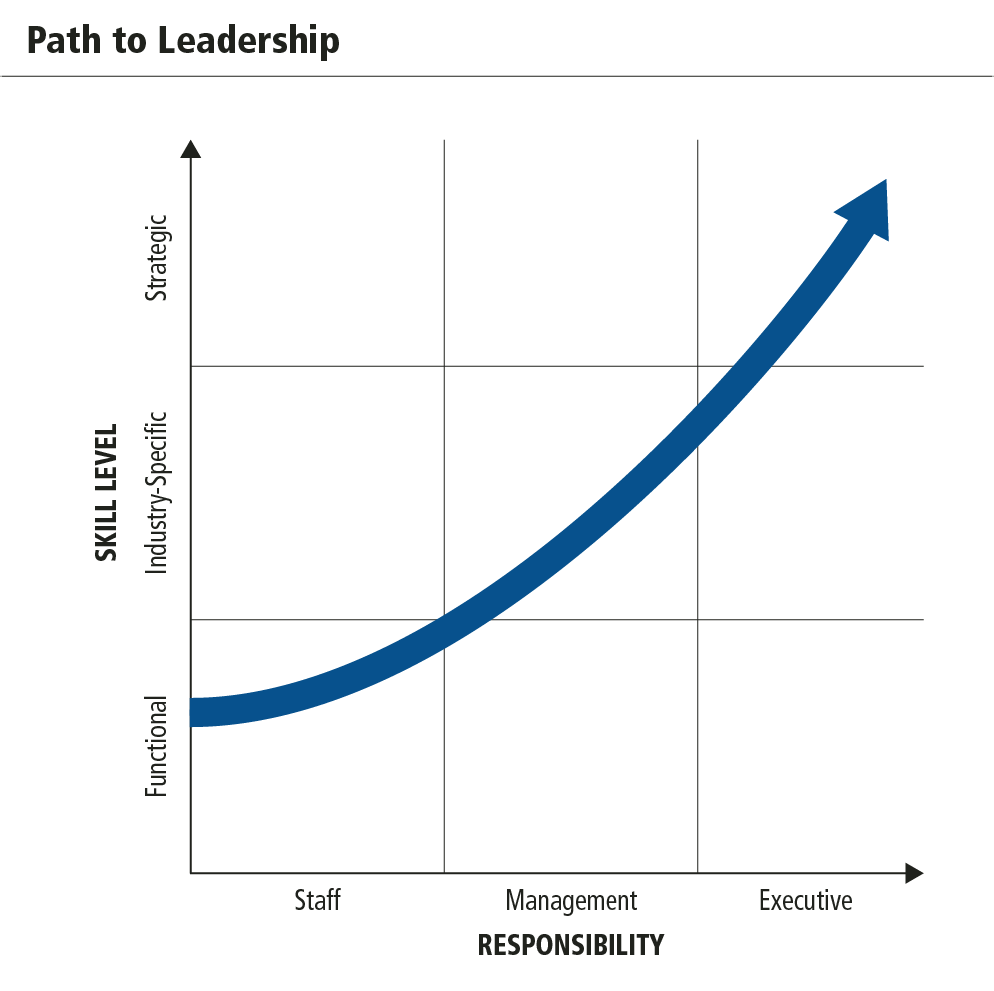

We have developed the diagram at right to guide our thinking on the needs of leaders in our sector. It is a representation of a fairly traditional leadership trajec- tory, where one’s responsibility and skill level are intricately connected. Ideally advancement of one’s responsibility level is precipitated by an increase in one’s skill level. However, that is not always the case. Depending on an individual’s path, skill gaps are inevitable. If someone starts out as a member of the program staff, as her career advances she will need to develop skills in finance or marketing. If she is looking for a promotion, she may want to improve her industry-specific knowledge of the arts and culture sector and get some of the bigger-picture, strategy skills. If an artist creates her own company, she may start out with knowledge gaps that need to be filled. In each of these scenarios, there is a likely solution online. There are many courses available that teach functional skills and strategic tools. And more and more sector-specific content is being produced.

Another issue with the arts and culture sector’s traditional leadership trajectory is who is represented in that arc, particularly who makes it to the top. Often the on-ramps to this path are riddled with barriers, like a costly master’s degree. As a result, there is a startling lack of diversity among leaders in the arts.

Again, it comes down to practicality and access. And while online education might not be a perfect solution, it does hold promise for addressing these issues for the arts and culture sector. We are still in the early days of these digital platforms; many are changing and growing every month. There are also efforts underway at the state and federal levels to chip away at the digital divide by expanding broadband access throughout the country.

We can all work to make sure more and more people see the on-ramps to arts and culture leadership and accept online education as a means to progress their careers. This will require more and more effort to sort through the ever-increasing array of options, the contextualization of the courses for arts leaders, and the legitimization of online coursework, certificates, and degrees.

Our own experience and conversations with leaders and people outside our sector tell us that now is the time to embrace and experiment with new ways of thinking and delivering knowledge — both theoretical and practical. The content of these offerings is, of course, important, but the delivery is equally important. Learning happens when the content is balanced (not overwhelming or underwhelming), has a consistent tempo from segment to segment or week to week, and is delivered in a compelling manner.

Learning support mechanisms will need to balance asynchronous and synchronous interactions and support application. This is not a short-term game. As a sector, we need to be committed to this work for the long haul. It is one where many can play and thousands will benefit if we do.

Our thanks to Andrew Ng, Coursera; Jennifer Hutton, California Institute of the Arts; James DeVaney, University of Michigan; Jesper Sørensen and Hayagreeva Rao, Stanford University; and Isaac Durand, Khan Academy, all of whom helped inform and form our thinking.

NOTES

- Laura Perna, Alan Ruby, Robert Boruch, Nicole Wang, Janie Scull, Chad Evans, and Seher Ahmad, “The Life Cycle of a Million MOOC Users,” Presentation at the MOOC Research Initiative Conference, 2013.

- Ho, Andrew Dean, Justin Reich, Sergiy O. Nesterko, Daniel Thomas Seaton, Tommy Mullaney, Jim Waldo, and Isaac Chuang, “HarvardX and MITx: The First Year of Open Online Courses, Fall 2012–Summer 2013,” HarvardX and MITx Working Paper No. 1, 2014.

- John Hansen and Justin Reich, “Socioeconomic Status and MOOC Enrollment: Enriching Demographic Information with External Datasets,” in Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, 59–63, ACM, 2015.

- Ezekiel J. Emanuel, “Online Education: MOOCs Taken by Educated Few,” Nature 503, no. 7476 (2013): 342–342.

- Thom File and Camille Ryan, “Computer and Internet Use in the United States: 2013,” American Community Survey Reports, ACS-28, US Census Bureau, Washington, D.C., 2014.

- Gayle Christensen, Andrew Steinmetz, Brandon Alcorn, Amy Bennett, Deirdre Woods, and Ezekiel J. Emanuel, “The MOOC Phenomenon: Who Takes Massive Open Online Courses and Why?” Available at Social Science Research Network 2350964 (2013).