Policy, Prisons, and Pranks: Artists Collide with the World

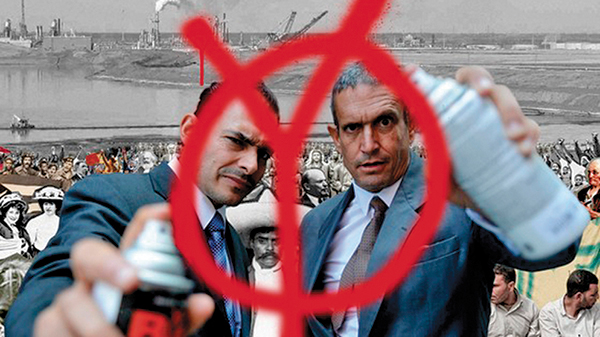

In Creative Capital’s very first year, a duo calling themselves RTMark applied to us for a series of pranks geared at “corporate identity correction.” They later changed their name to the Yes Men and became notorious for their work in tactical media, like impersonating Dow Chemical executives and apologizing — and offering to make restitution — for Bhopal on the twentieth anniversary of the disaster. This put Dow in the unenviable position of having to say that they had no intention of making restitution, but not before the Yes Men had appeared on the BBC and the news spread to media outlets all over the world. Dow’s stock took a major dive for at least a few hours! Now through their Yes Lab, they are training other activists in the ways of “laughtivism,” their highly honed brand of global activism that uses humor to make critical points.

The fourth-generation farmer and artist Matthew Moore asked us to support a video project for grocery stores that would help shoppers connect to the sources of their food. He couldn’t have seen the myriad ways that this lyrical idea would explode into the Digital Farm Collective, which is now documenting crops growing around the world as well as the farmers’ growing philosophies. Matt recently launched an app and curriculum for schools so that kids can make their own time-lapse videos in their community and school gardens.

Food artist Robert Karimi uses the format of a TV cooking show to engage audiences around diet and diabetes in communities of color. He employs cultural ritual and stories, uniting cooking and interdisciplinary art to promote well-being. He has now incorporated his own nonprofit, the impact of his work has been studied at Arizona State, and he has personally fed more than 20,000 people through his performances over the past three years.

Environmental artist Jae Rhim Lee asked us to support her Infinity Burial Project, in which she is building open-source, DIY, mushroom-based burial containers that will help our bodies decompose more quickly and greenly at death, including a mushroom death suit and burial pod. Her goal is nothing short of the transformation of the funeral industry, which is highly toxic for both the workers and the earth. In the early years of her project, she was thrown out of discussions at funeral director conferences, but her project is now being featured at the National Funeral Directors Association’s annual convention, which is taking place this week in Austin! You can join the cause by becoming a member of her Decompiculture Society as a Decompinaut.

In 2008, we supported two acclaimed documentary projects, The Oath, by Laura Poitras, a film about Osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard, and Trouble the Water, by Tia Lessin and Carl Deal, an amazing film about Hurricane Katrina that was nominated for an Oscar. They have moved forward with new projects, with Laura now working on a film about whistleblowers and Tia and Carl producing Citizen Koch, about the influence of corporate money on our political system. The name of their production company is Elsewhere Films, because as Tia told me, they realized early on that support for their work would likely need to come from nontraditional sources and audiences.

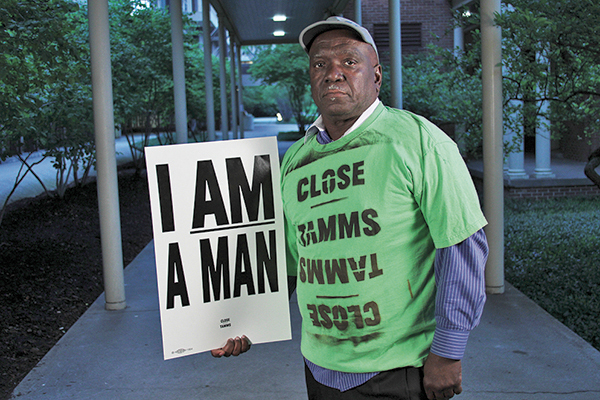

And Laurie Jo Reynolds, one of our newest grantees, was recently in the news for a project she embarked on more than ten years ago. She began with a poetry project intended to provide outside contact and an outlet to prisoners in permanent solitary confinement in the Tamms “supermax” prison in Illinois. The letters she received in response led her to collaborate with prisoners’ families and local lawmakers in a multiyear campaign that led directly to the closing of this inhumane prison. She calls her artistic practice “legislative art.”

In his book The Age of the Unthinkable, Joshua Cooper Ramo, a former editor at Time magazine, says that “there are forces for change at work that are invisible using old ways of seeing.” He says that “the source of the greatest historical disasters is that so few people at the time either recognize or understand the shift.” And then his next sentence surprised me: “Artists,” he says, “with their tuned instincts for the new, often do.”

When we set out to support individual artists’ projects in 1999, I don’t think I could have predicted that we would be supporting tactical media artists, laughtivism, hybrid artists such as farmer-artists, bio-artists, engineer-artists, technologist-artists, and legislative artists, among many others, including some who would land on the front pages of the New York Times, and not with reviews of their artwork! Or that, in some cases, I might need a direct line to the ACLU and People for the American Way.

Early on, one of our grantees said, “I feel you are trying to create an organization that mirrors the creative trajectory.” That statement made me realize that perhaps we needed to be our own art project. So, then the question is, operationally, day to day, what does that mean?

I thought I would share some observations about the artists who are challenging us with their “new ways of seeing.” Are there organizational lessons to be learned from the ways these twenty-first-century artists are operating?

- Many artists today expect to be able to cross disciplines in their work and create projects on multiple platforms. They want the book, the app, the webisodes, and the gallery installation. In this they defy categorization and they don’t want to be categorized. Providing access to resource people who work in a variety of artistic disciplines has become a necessary aspect of our support system. But do we have enough producers who are equally conversant in all of these areas? And, as one artist said, “I got to be undercapitalized in four different disciplines instead of just one!” Where will the financial support for these ambitious visions come from?

- Many of the artists we work with borrow titles and structures from other sectors to provide an air of legitimacy for often wildly provocative ideas. These include the Ghana ThinkTank, the Center for PostNatural History, the International Museum of Radically Ordinary Things, and the Bureau of Inverse Technology. These artists and the institutions they create use these recognizable formats to promote imaginative and often subversive ideas about issues such as immigration or genetic modification, and by adopting these “legitimate” structures, they are also questioning the authoritative role they play in our culture, and in shaping our consciousness. I have often joked that Creative Capital is a “fake” foundation, since we aren’t endowed and have to raise every penny we give out. Could we be more imaginative in how we employ our institutional status?

- The work some of these artists do can be difficult for exhibitors and programmers to present, since it is often process based and iterative. One of the most popular sessions at our recent retreat was on the “anti premiere.” What do we do when there is no one fixed date in time when an artist feels a project will be finished? Many artists are also interested in presenting their work in nontraditional spaces — out of doors, in hotel swimming pools, high school gyms, et cetera, as we spend more and more money building extravagant traditional presentation palaces. How will presenters and service organizations support work that extends so far beyond traditional parameters? Does this change how we need to think about helping artists build audiences for their work?

- This generation of artists is generally much more media and tech savvy than ever before. The Yes Men have been on Jon Stewart. Tia Lessin and Carl Deal’s Citizen Koch saga was in the New Yorker and the New York Times, and the artists wrote an op-ed in the Huffington Post. Laura Poitras was on the cover of the Sunday New York Times Magazine after she helped break the Edward Snowden story. We have seen this mainstream media attention greatly expand the impact of these artists’ reach to nonarts audiences. We want to study their successes, to learn how to be as savvy as they are!

-

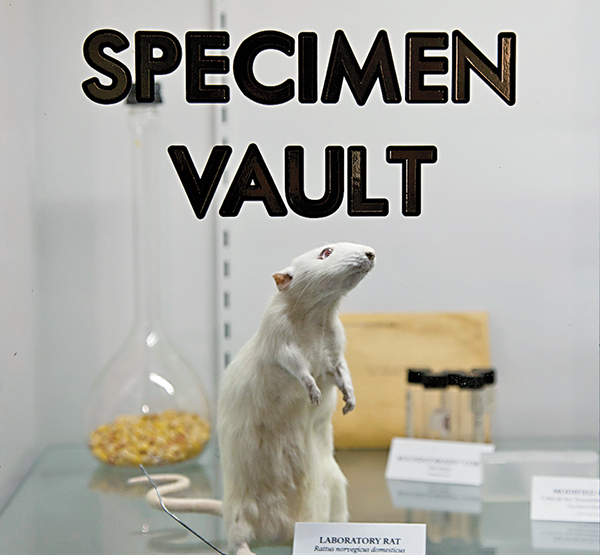

Richard Pell. Specimens from the Center for PostNatural History, Pittsburgh, PA. Courtesy of the Center for PostNatural History.

These artists are very results oriented: they don’t just want to create “awareness” of issues or just employ the rhetoric of change; they want to see things actually change. Tia and Carl want to overturn the Citizens United ruling. Laurie Jo wants to shut down other supermax prisons. Laura Poitras wants us to reexamine our foreign policy. St. Louis artist Juan William Chávez wants to turn the vacant thirty-three-acre site where the failed Pruitt-Igoe housing project once stood into public space for urban gardening and beekeeping. And Ghana ThinkTank, whose slogan is “Developing the First World,” actually takes our problems and exports them for solution to the developing world, reversing hundreds of years of our visiting our so-called wisdom on the rest of the world. Do we have the right resources in place, human and financial, to be a useful partner in these powerful efforts? What is missing? Do we need to change? How?

- We have always thought of artists as entrepreneurs in the cultural arena, and each individual project as its own entity, and increasingly we have worked to tailor and individualize our work with grantees. But now, we are also beginning to see some artists — a vanguard, but I think we will see more — moving from project to enterprise in a more conventional way, in order to achieve their impact goals. A number of these artists are experienced and/or formally trained in fields other than the arts, and they might come to us initially with a relatively contained project, but with something that could be scalable, either in the profit or nonprofit sector. Now we need to figure out how to support artists as they work toward more ambitious goals. This will demand more of us in terms of helping people think about building their businesses, and requires different information and resources. For example, what is the right legal structure for the entity — for profit or not for profit, or a hybrid structure? If people choose a for-profit route, how can we help them locate investors? Who is the constituency or market, which might not be the same as for the artist’s art projects? To support artists who aspire to be agents of change at this enhanced level, we need a new toolkit — and connections to a whole different set of people — in order to create a multifaceted team dedicated to the success of each enterprise.

- And finally, we fund projects, but we really go on journeys with our artists, and sometimes that journey leads to Broadway or an Oscar nomination, and sometimes it leads to the NSA or the FBI. Laura Poitras lives in Berlin now because she is detained and her hard drives are wiped every time she enters or leaves the US. Tia Lessin and Carl Deal lost $150,000 in public television funding for Citizen Koch, but raised about $170,000 from more than 3,000 individual donors on Kickstarter. We all acknowledge that a commitment to innovation means an embrace of risk and possible failure, but we don’t talk about the fact that sometimes the courage that leads to success and impact can bring punishment as well. What does it mean to support work that might have serious PR blowback or maybe even legal implications? How do we (and our boards of directors!) pragmatically and meaningfully support this work, and how far should our support go?

Lauri Jo Reynolds. Melvin Haywood, activist in Tamms Year Ten campaign.

Photo by Lora Lode/Tamms Year Ten.

The writer James Baldwin said, “Everybody wants an artist on the wall or the library shelf, but nobody wants one in the house.” Well, these artists are in your house, at your grocery store, on TV, in your newspaper, and at your funeral parlor. They are revolutionizing the art world, shaping conversations in their communities; they are shaking up national policy conversations.

I have read that we will experience more change in the next thirty years than we have in the past three hundred. So there is an urgency in engaging with these kinds of questions. What do we need to do to “bake” change into the very DNA of our organizations? If we truly believe that our artists are change agents, are we equipped to be change agents also?

“I saw the angel in the marble,” Michelangelo said, “and carved until I set him free.” Are we confident enough to allow our organizations to “reveal” themselves to us, telling us at every step of the way what they want — and need — to become?