Introducing Community Innovation Labs

A New Approach for Harvesting the Power of the Arts to Unlock Complex Problems in Local Systems

Download:

![]() Introducing Community Innovation Labs (395 Mb)

Introducing Community Innovation Labs (395 Mb)

Meg Wheatley

Charles Darwin

Adam Kahane

Antonio Machado (tr.)

As old-fashioned planning fails us more and more at the community level, we need to address stubborn community challenges in new ways. We need laboratories — spaces for deliberate experimentation — that bring networks together, bridge differences, and unfreeze the status quo, so that innovative responses can emerge that were previously inaccessible. In a lab context, creative practices, so often kept at the margins of community change processes, can play a central role in reframing the problem, building essential trust, and fostering the discovery of new connections and possibilities. In this article we introduce Community Innovation Labs, a new approach that brings together learning from social innovation labs and creative placemaking projects. These labs offer the opportunity for deep-tissue work on systems change that is creative, locally owned, and authentic. Seeing the opportunity, local and national grantmakers are coming together to invest in a people-centered approach that suggests we can build the capacity for long-term civic renewal.

What is the context for this work?

We are living in a time of rapid social change. In the past ten years the country has inaugurated its first black president, legalized gay marriage, and democratized the flow of news and information through social media. Yet, the country faces increasing disparities and unprecedented social and cultural challenges. One in five US families officially lives in poverty, while the wealthiest 0.1 percent of the population holds more of the country’s wealth than the bottom 90 percent combined.1 Incarceration rates remain the highest of any country in the world.2 And it seems that views are increasingly polarized, efforts at change are fragmented, progress is glacial, and ingrained ways of working exclude most citizens from real impact on decision making.

It is easy to feel discouraged and apathetic about all this. As we struggle to deal with — or even to understand — the incredibly complex, many-layered issues that surround us today, the challenges can appear too difficult to take on. Change efforts are splintered into factions with competing agendas and demands, and, as a result, the system seems continually to revert to old and injurious patterns, often deeply rooted in decades and even centuries of American policies, power structures, and culture.

At EmcArts, we are trying to build on the experience of our past ten years of facilitating adaptive change in the arts to see how we might be of greater use in this turbulent context. We are developing a new approach we call Community Innovation Labs. We want to support the individuals, organizations, and communities that we work alongside to get beyond a sense of stuckness and to dissolve some of the fault lines that foster territorial dynamics and inhibit generous dialogue. Only if we can do this, we believe, will our communities make the real progress toward justice, equity, and creative vitality on which the fundamental health of any mature country depends.

Despite our best intentions to achieve these aims, we are getting it wrong so often these days — still applying military metaphors and mechanical actions (targets, precision, efficiency) to situations that have become complex and fluid, unknowable and ambiguous. We are holding ourselves back by relying on the best practices of the past and top-down strategic plans that limit our ability to discover the next practices of the future or tackle anything other than symptoms.

To unlock these complex challenges, we need unconventional approaches that bring lots of viewpoints together across boundaries. We have to draw policymakers, nonprofit executives, corporate leaders, and others traditionally empowered by the system into new relationships with activists, organizers, youth, faith leaders, community members, artists, cultural workers, and others traditionally excluded in order to imagine and design new ways forward. We know that systems can change for the better if people are brought together to discover common purpose and given space to explore mutual interests. And we know that the creative sector can play a vital role in community transformation, using artistic practices to build a shared vision, explore new possibilities, and advance creative solutions.

Instead, grantmakers still tend to fund quick solutions to complex problems (the best bright idea, the demonstration project, the Shark Tank), when in fact, to respond effectively, we all need to slow down and reframe the problem, build new relationships, and let go of ingrained attitudes and assumptions. In addressing complexity, many funders require that outcomes are known in advance, when by definition they cannot be. They want linear metrics, logic models, and theories of change, when any future that will be usefully different is going to emerge only from experimentation. The accountability environments that seem to rule our lives demand a plan that is developed up front and followed in lockstep, when what our communities would benefit from most is to invest in people, promote divergent thinking, and uncover previously unimaginable paths.

Even if we can do this, working with the interests of many stakeholders to find new solutions to complex shared challenges is itself a difficult and delicate business, and the world’s knowledge is in its infancy. Attempts on too large a scale typically result in fine words but little active implementation (as in the Kyoto Protocol on climate change, which remains mired in political maneuvering), while attempts at the level of single organizations typically come up against insufficient capacity or leverage for any lasting impact on the system to be felt.

What we need to do is to mediate between these traditional extremes. To come up with strategies that have a chance of transforming our deeply stuck systems, we have got to try divergent strategies, not align around one, and work locally, side by side with the stakeholders affected by the system. In any complex system, it is impossible to design a single perfect solution that works for all, even with the help of highly qualified experts. Quite the opposite, it takes repeated prototyping of many different approaches with the people who hold the problem to find solutions with real traction.

That, at least, is what we are setting out to explore through Community Innovation Labs.

What are the practices we are building on?

The development of the Community Innovation Labs draws on two new, yet substantial, bodies of practice in community change and the arts: social innovation labs and creative placemaking.

Learning from Social Innovation Labs

We have scientific and technical labs for solving our most difficult scientific and technical challenges. We need social labs to solve our most pressing social challenges.3

During the past ten years, the global phenomenon of laboratories for social innovation has taken off rapidly as an alternative to traditional planning in circumstances where the complexity of the social problem demands systemic transformation and where the future is not linear or predictable but emergent. “Social labs confront complex, messy, and non-linear challenges that transcend the interests of a single institution or sector.”4

Social labs around the world are boldly taking on some of the most stubborn, complex challenges we face today: youth unemployment in the United States, the unsustainability of our global food supply, inequities in our global finance system, and food waste and spoilage in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and the United States.5

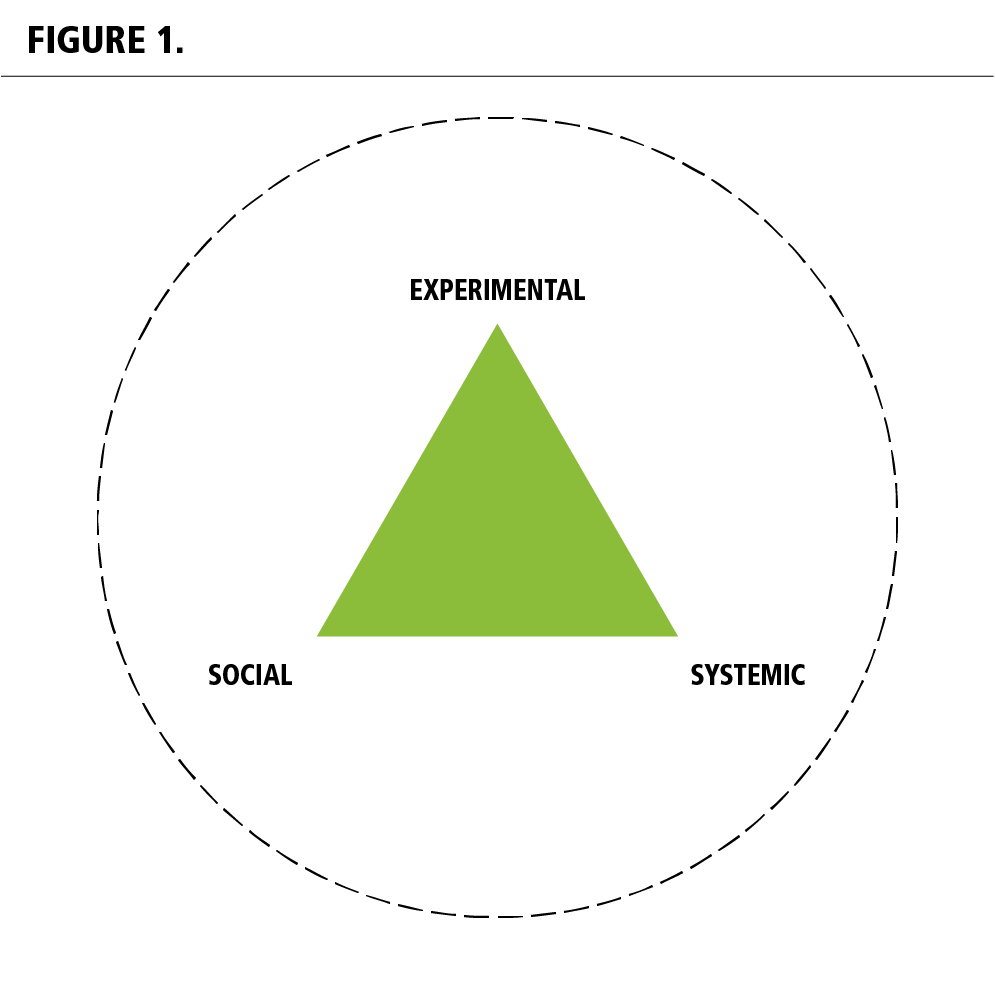

Defined by three characteristics, social labs are (1) systemic in nature, in that they are designed not only to engage with the symptoms of a problem but to transform the system as a whole; (2) social, in that they invest in the team, not the creation of a plan; and (3) experimental, in that outcomes are fundamentally uncertain, and new approaches are uncovered by repeated prototyping.6 (See figure 1.)

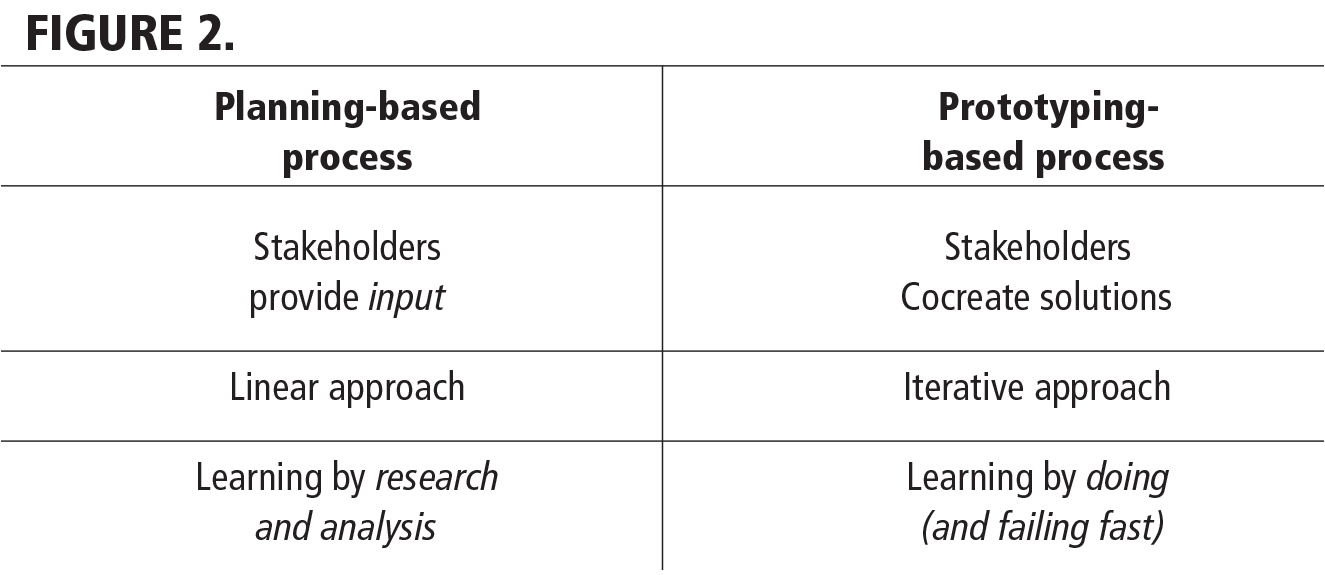

Social labs are a part of a paradigm shift — from the strategic planning paradigm that is dominant today, to a paradigm of experimentation as a way of understanding the world.7 (See figure 2.)

Social labs echo our established practice at EmcArts because they employ carefully crafted process frameworks over an extended period of time and seek to make change sticky by delaying immediate action to create space for reframing, building relationships and networks, and letting go of old assumptions. These are key principles that undergird our existing innovation labs in the arts.

Learning from Creative Placemaking

The second practice that the Community Innovation Labs draw on is creative placemaking, a new term coined to capture the creative work of artists in community development.

As in social innovation labs, there has been a tremendous surge in projects, attention, and support for creative placemaking in the past five years. There is less clarity, however, on what the term means and what the practice involves. It is generally accepted that the term came to wide use following Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa’s 2010 study in which they first defined the term: “In creative placemaking, partners from public, private, non-profit, and community sectors strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, city, or region around arts and cultural activities.”8

The number of definitions has grown since then, including those of The Kresge Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.9 ArtPlace America’s definition specifies four characteristics of successful creative placemaking projects,10 locates areas of intervention within ten sectors of community planning and development, and also emphasizes processes that feed into community outcomes. “In creative placemaking, ‘creative’ is an adverb describing the making, not an adjective describing the place. Successful creative placemaking projects are not measured by how many new arts centers, galleries, or cultural districts are built. Rather, their success is measured in the ways artists, formal and informal arts spaces, and creative interventions have contributed toward community outcomes.”11

Looking across these definitions, creative placemaking can be seen as a strategy, a practice, an outcome, an intervention, or all of the above. What seems to be shared across this emerging field is a belief that artists, artistic practices, and cultural organizations can play a critical role in civic life and community development. We can see this in the work of Theaster Gates’ Dorchester Project in Chicago, the Station North Arts District in Baltimore, ArtsQuest in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, the ZERO1 Biennial in San Jose, and so many more.

The practice of creative placemaking resonates deeply with what we have seen during the past ten years at EmcArts, as we have worked alongside more than three hundred arts organizations wrestling with their most complex challenges: staying relevant and serving their communities in new ways. We know firsthand that artistic practices have a tremendous potential that is only beginning to be unleashed to explore alternative pathways, reduce barriers to understanding, and find common purpose.

What is the opportunity?

Through our research, we identified a significant new opportunity to enable communities to take on intractable challenges by combining key features of social innovation labs and creative placemaking together into our new Community Innovation Labs.12 While both of these emerging practices have already made tremendous impacts, each still has significant gaps and limitations, which create new opportunities for learning.

Zaid Hassan, author of The Social Labs Revolution, on artistic practice:

Artistic practice is integral to the labs approach. We have made use of improv and theatre to understand power dynamics in groups. Teams have built physical models of highly complex systems in order to understand causal drivers and system dynamics. We have used bricolage to help diverse teams “think with their hands,” come up with and rapidly iterate shared responses. Broadly speaking, artistic practices support the shift from purely cognitive modes common in professional contexts to a more integrated “head, heart and hands” response. These are more sustainable, in part, because an emotional or physical shift is a better “fuel” for driving changes in behavior.

Systemic change is impossible without real emotional shifts. The work of labs will truly come into its own once we grasp that not simply what we do matters, but the stories we tell about what we do matter as much.

I believe that too many of us are in the Stone Age when it comes to understanding and utilizing the power of artistic practices in creating systemic change. The work we have done to date represents very early steps. The journey of incorporating artistic practice is not just interesting or important but imperative. We will not address our most profound challenges without undertaking this journey.

For example, while social labs offer rigorous, carefully crafted process frameworks for change, they rarely engage artists, artistic practices, and cultural organizations in a significant way. This seems a major opportunity to build on previous lab designs, considering the need for creative problem solving and nonlinear thinking to take on systems-level challenges. We see the integration of artists and artistic practice into a lab framework as a significant opportunity for these labs to be deeper, more imaginative about systemic solutions, more effective, and sustainable. Bringing artists and artistic practice to the work of system transformation can engage hearts and hands as well as minds, introduce metaphorical thinking in situations typically limited to the mundane, use narrative methods to counterpoint more traditional data, bring diverse groups into meaningful exchange with each other, and generate real innovative connections where only disparate interests may have previously been recognized.

At the same time, we noticed in our research that the predominant model for funding creative placemaking was to support single projects and/or single organizations, rather than building civic capacity to integrate art and artists into community development efforts now and into the future. While creative placemaking has produced many exceptional projects that beautify public space, parks, bridges, buildings, transit stations, and main streets, we believe that the current funding model may not be engaging the full capacity of artists, which more broadly includes the ability to creatively solve problems, generate new ideas, forge social bonds, and identify the right questions to ask. And beyond that, support is needed to build the capacity of local leaders and organizations to manage the complex dynamics of this multistakeholder work.

The aim of Community Innovation Labs is to catalyze deeper, more sustainable, more creative approaches to system change. We see grantmakers across the country — in the arts but also far beyond that sector — beginning to recognize this need and investing in teams of local network leaders who are committed to working together in new ways and over extended periods to seriously address persistent problems in their communities.

What are the approach and potential impacts?

In two US communities, EmcArts is working with numerous funding partners (national and local) to pilot this new approach to solving tough social challenges by deeply integrating artists and artistic experiences into rigorously designed and facilitated change processes. Community Innovation Labs are currently active in Providence, Rhode Island (tackling community safety and cultural development issues in the Trinity Square neighborhood), and Winston-Salem, North Carolina (tackling inequities in employment, income, and wealth). Following intense interest from more than sixty communities across the country, more labs are planned to launch in 2016.

Michael Rohd, Center for Performance and Civic Practice, on the power of artists as facilitators:

Artists whose own work demands collaborative practice can make powerful allies in community change contexts. Their contribution can take the form of artistic output that supports change efforts; it can take the form of creative advocacy efforts; it can engage creative process as a tool for coalition-building and problem-solving with disparate and/or like-minded stakeholders. These possibilities, a spectrum of activities that span work an artist makes for change efforts, to process work an artist develops with other agents of change, make for an arsenal of approaches that some artists deploy as facilitators within community change efforts.

Facilitation is in itself a set of skills that may include but is not defined by a creative practice. In my experience, it involves deep listening, a passion for inquiry, and an ability to synthesize varied viewpoints while working with groups to move collective goals forward. Artists experienced in collaborative practice most often possess these skills. When they begin to explore their artistic practice in the context of community facilitation, they bring with them deep backgrounds in the devising and deployment of imaginative, expressive actions.

Supporting the visibility and professional development of diverse, region-specific artist/facilitators benefits community change efforts. It increases local capacity for meaningful community development and helps build networks of vested, skilled leaders.

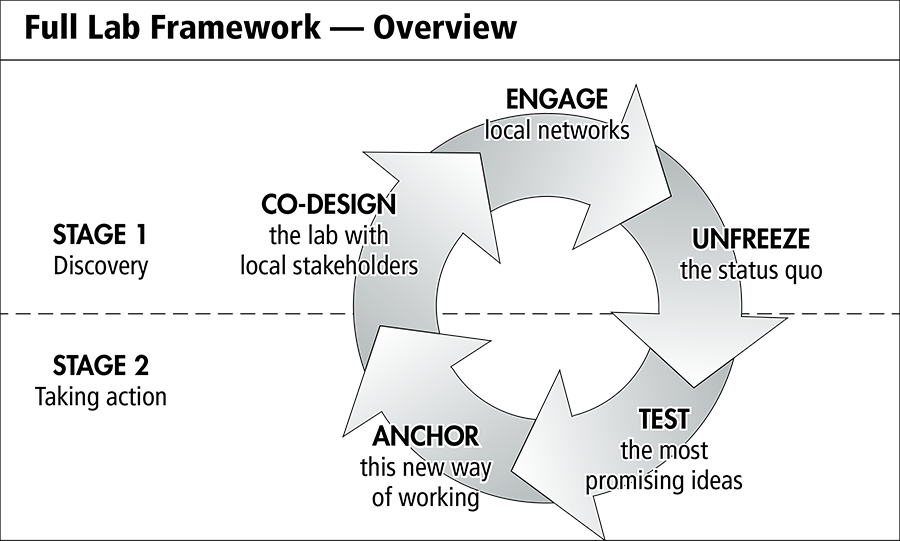

Each pilot lab is bringing together a diverse, cross-sector group of network leaders to tackle a specific and urgent local challenge in civic and cultural life. The design we have evolved combines what we hope is sufficient rigor for an unusual depth of inquiry to be sustained, with enough space for discovery and emergence that transformation can occur. As the following figures show, the process framework has five stages. It starts with the development of a central leadership team (including six to twelve local champions of the lab and EmcArts staff) for codesign, network analysis so that the champions can reach beyond their “usual suspects” to engage up to forty local network leaders as lab participants, followed by multiday convenings of the participants to explore and reframe the central problem. The idea behind all this discovery work is that it will create the conditions for new networks of shared interest to emerge — clusters of consortium-based innovation initiatives, each of which will be supported for an intense period of repeated prototyping in response to the challenge (pursuing divergent experimental directions rather than aligning around a single proposed overarching response). The final formal stage of a lab involves engaging champions, participants, and wider networks of community stakeholders in reflecting on their new practices and anchoring these ways of working together in the community, so that EmcArts’ contribution can wind down and new local capacities can be applied to other complex challenges as they arise, long after the lab intervention is over.

Adam Kahane has summarized the psychological and social through line of this type of work: “Actors transform their problematic situation through transforming themselves, in four ways: First, they transform their Understandings; then, their Relationships; then, their Intentions; and finally, their Actions.”13 Kahane’s insight is that transformation in how we act is only likely to be authentic and sustained if it arises from deeper shifts in our way of being in the world, shifts that artists can help us apprehend; and that the power to change systems ultimately comes down to individuals, the participation of all those who are implicated in how and why the system continues to work the way it has. These axioms underpin the aspirations that drive the Community Innovation Labs.

Regina Smith, senior program officer, Arts & Culture, The Kresge Foundation, on supporting the pilot labs:

This work aligns with the Kresge Foundation Arts and Culture Team’s Pioneering New Approaches portfolio, which is designed to test new approaches in breaking down the barriers to widespread adoption of creative placemaking. Early in the development of its program strategy, the team identified a set of barriers as part of its theory of change including an arts and cultural sector that is often disconnected from or not aware of broader community development efforts.

EmcArts’ pilot Community Innovation Labs seek to address this and other barriers and to develop the appetite and conditions required to sustain creative placemaking in local systems through a carefully constructed and facilitated framework that creates a safe “practice space” to empower individuals and organizations to think and act differently, rather than defend territory or dismiss unusual approaches. Recognizing that finding and sustaining solutions to complex adaptive challenges is primarily a process, these pilots and our grant will contribute to increased knowledge about how to integrate the work of arts and culture more fully into the design and execution of community change efforts.

There is a kindness built into this approach, a deep caring for each other and a recognition of what ultimately makes us the kind we are, our kinship, that we believe the labs may be able to mobilize for transformative work. Four leaders offer passionate and compelling insights that inspire us as we move this effort forward.

In their book On Kindness, psychologist Adam Phillips and historian Barbara Taylor recognize the risks and rewards of kindness:

Akaya Windwood, president of the Rockwood Leadership Institute, wrote recently:

And Donella Meadows, one of the founders of modern systems thinking, articulates the emotional source of the humility that attends real power:

NOTES

- Thomas Gabe, Poverty in the United States: 2013 (Congressional Research Service, 2015); Angela Monaghan, “US Wealth Inequality — Top .01% Worth as Much as the Bottom 90%,” The Guardian (US edition), November 13, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/nov/13/us-wealth-inequality-top-01-worth-as-much-as-the-bottom-90.

- Tyjen Tsai and Paola Scommegna, “U.S. Has World’s Highest Incarceration Rate” (Washington, D.C.: Population Reference Bureau, 2012).

- Mia Eisenstadt, Zaid Hassan, and contributors, The Social Labs Fieldbook: A Practical Guide to Solving Our Most Complex Challenges (Creative Commons Attribution, 2015).

- Hendirk Tiesinga and Remko Berkhout, Labcraft (London and San Francisco: Labcraft Publishing, 2015).

- Some examples of social innovation labs are The Finance Innovation Lab; University of Waterloo/MaRS Solutions Lab on youth employment; and Sustainable Food Lab, Global Knowledge Initiative Waste and Spoilage project.

- Zaid Hassan, Social Innovation Labs Revolution (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2014).

- Eisenstadt, Hassan, and contributors, The Social Labs Fieldbook.

- Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa, Creative Placemaking, A White Paper for The Mayors’ Institute on City Design, a leadership initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with the US Conference of Mayors and American Architectural Foundation (NEA, 2010).

- According to The Kresge Foundation, creative placemaking is “simply the deliberate integration of arts and culture in [community] revitalization work.” The National Endowment for the Arts’ Our Town program uses this definition: “Striving to make places more livable with enhanced quality of life, increased creative activity, a distinct sense of place, and vibrant local economies that together capitalize on their existing assets.”

- “About ArtPlace,” http://www.artplaceamerica.org/about/introduction: “At ArtPlace we believe that successful creative placemaking projects do four things:

- Define a community based in geography, such as a block, a neighborhood, a city, or a region

- Articulate a change the group of people living and working in that community would like to see

- Propose an arts-based intervention to help achieve that change

- Develop a way to know whether the change occurred”

- Ibid.

- In our exploration of process frameworks for systemic change, we learned a great deal from other established approaches to joint problem solving at the community level. From the Collective Impact movement, we took inspiration from the emphasis placed on developing a shared vision of the future. From the U-Process, we learned about the way action is intentionally deferred to create space for reframing, building relationships and networks, letting go of old assumptions, and seeing the system as a whole. From Transformative Scenario Planning, we learned that system transformation depends on sequences of personal transformation: first, transformed understanding, and only then transformed relationships, intentions, and actions.

- Adam Kahane, Transformative Scenario Planning (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2012).

- Adam Phillips and Barbara Taylor, On Kindness (London: Picador, 2010).

- Rockwood Leadership Institute newsletter, May 2015, http://rockwoodleadership.org/downloads/1505_newsletter_full.html, accessed July 23, 2015.

- Donella Meadows, Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System (Sustainability Institute, 1999).