Getting Beyond Breakeven

A Review of Capitalization Needs and Challenges of Philadelphia-Area Arts And Culture Organizations

This study was commissioned and conducted in late 2007 and early 2008, before the severe economic downturn in the fall of 2008. In this context, the first question we address is a simple one: Why talk about capitalization, especially now when so many organizations are struggling just to survive? For nonprofits financial performance is not the sine qua non of exemplary overall performance, and balance sheet analysis cannot measure social impact or artistic excellence.

So why should nonprofit arts organizations care about capitalization? TDC posits that financial health and mission impact are linked for a number of reasons. First, undercapitalization is distracting and debilitating, making it challenging to maintain the focus and energy necessary to conceive and produce the highest quality artistic programs.

Second, undercapitalization can chill artistic risk-taking.

An organization one failure away from closing has a strong incentive to choose the tried and true over the experimental. Even before the radical downturn in the environment, rapidly changing consumer tastes and habits were challenging the traditional business models of arts organizations. Without adequate capitalization, cultural organizations are hard put to pursue innovative strategies to address the changes in the marketplace.

Finally, undercapitalization puts organizations at risk of failure. The squeeze of straitened resources and narrowing options resulting from the economic downturn has placed the risks of undercapitalization into sharp relief. Those organizations with solid capital structures have the capacity to last through the rainy day. Those that don’t are already pressed. The purpose of discussing capitalization now is to grasp the teachable moment and to help viable organizations create realistic plans as they adjust their strategic goals to fit a new, uncertain landscape of funding and audience engagement.

This discussion of capitalization falls into a field primed both in theory and practice. Long-time players in the sector include the Nonprofit Finance Fund and National Arts Strategies and this study has built on their invaluable thinking.

What is Capitalization?

Capitalization is the accumulation and application of resources in support of the achievement of an organization’s mission and goals over time. The province of capitalization is the balance sheet, which encapsulates the record of an organization’s financial performance as net assets and measures the magnitude of its assets and liabilities. A strong balance sheet evidences an organization’s ability to access the cash necessary to cover its short- and long-term obligations, to weather downturns in the external operating environment, and to take advantage of opportunities to innovate. Conversely, an undercapitalized organization often falls short of these capabilities.

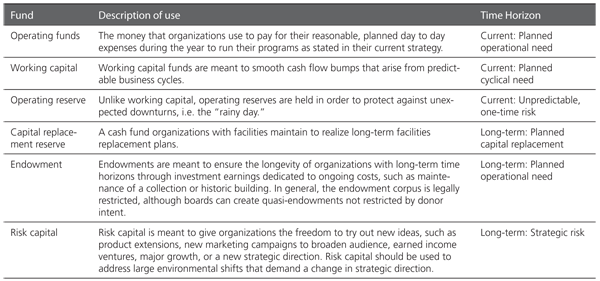

Unpacking the balance sheet. There are six distinct types of capital funds, described in the table below, that managers can use to maintain organizational health. Each of these funds addresses a distinct need.

Not all organizations require all of these funds. The nonprofit sector is plagued with misconceptions about the different types of capital funds and their use. The proper scope and scale of capital structure can only be determined after an examination of an organization’s time horizon, core business model drivers, and lifecycle stage.

Time horizon. Time horizon is an essential consideration when matching an organization’s mission to a capital structure. On one end of the spectrum are organizations that live in the present day, seeking to address the needs of the current-day population and realizing a single person’s innovative idea or artistic voice. They may be low budget, driven with sweat equity of a committed staff. In the middle range are organizations that are invested in a logic model, brand, or regular audience or membership. At the long-term end of the spectrum are institutions that are committed to stewardship of buildings and collections and that are investing to meet the needs of future audiences.

Organizations that are more concerned with present-day needs require more flexible capitalization, while those with the obligation to look to the future need permanence and stability.

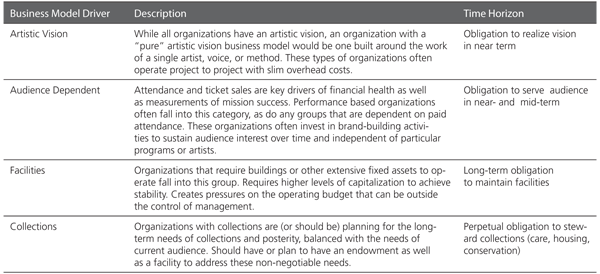

Business model drivers. To build our evaluative model for capitalization, TDC defined four basic business model drivers, described in the table on page 31, each of which has an associated time horizon. Few organizations could be confined to only one of these buckets.

What Were the Study’s Core Questions and Methodology?

The study’s core questions were:

- To what extent are nonprofit arts and culture organizations in the Philadelphia area capitalized adequately to enable achievement of their missions?

- Do local nonprofit cultural leaders understand the relationship between capital structure and achievement of organizational mission, and is that understanding evident in their decision-making and actions?

- Does the system of incentives and technical assistance help to improve the financial health and capitalization of cultural organizations?

TDC used both quantitative and qualitative analysis to answer the core questions. Using the Pennsylvania Cultural Data Project (PACDP) dataset, we evaluated the financial position of 158 organizations. 2 The majority of the available data were drawn from fiscal years 2005 and 2006. We interviewed a subset of 60 organizations to evaluate financial literacy. We researched the funding and capacity building environment by interviewing 12 local and national arts funders, 5 local service providers, and 11 outside experts, and reviewing the literature on nonprofit capitalization and financial health.

TDC designed a classification system that defined four scores, from one being strongest to four weakest. The strongest organizations had the ability to meet their financial obligations, weather downturns, invest in new ideas, and were best positioned to achieve their missions. The weakest organizations were severely constrained. To classify organizations, we conducted a financial statement analysis. Primary consideration was given to the condition of the balance sheet, the levels of liquidity, working capital, and available unrestricted net assets, in the context of the budget size. Special attention was paid to the management of restricted funds and deferred revenue, which is easily overlooked as a risk factor, but is a leading indicator of a strapped organization borrowing from its future operations. Secondary analysis focused on revenue and expense factors, such as proportions of contributed and earned revenue, funding of depreciation and debt service, and patterns and scale of net surpluses and deficits. TDC also designed a classification system for financial literacy, which measured understanding of the balance sheet and financial operations, ability to articulate capitalization needs, ability to project forward, and ability to set the organization’s financial structure in the larger context of the sector and the regional environment.

It’s important to note that the measures TDC used to judge adequate levels of capitalization are more complex than the two more universally accepted yardsticks in the nonprofit world—a balanced budget with a modest surplus that ties to the stated objectives of an organization, and a positive unrestricted fund balance. This study has asked us to hold organizations to a different—longer range—standard.

This study reveals that if organizations and their supporters want to assure their long-term viability they need to build on current achievements and create a new set of measures. 3

And yet – this more comprehensive set of measures may not be necessary for the entire sector. Some organizations by their very nature may be created to present a unique artistic voice for the duration of that voice. This study did not cross reference the artistic quality of an organization’s offerings with its financial condition.

|

|

What Were the Study’s Core Findings and What Are the Implications?

The results of the study are sobering, even more so when considering the fact that it was completed in spring 2008 before the economic downturn.

Weak financial health. The study confirms what organizations and funders knew already: Arts organizations at all budget sizes and in all disciplines have troubling balance sheets and highly constrained capital structures. We found that 77 percent of the organizations we reviewed fell into classes 3 and 4, the weaker end of the spectrum.

There was surprisingly little variation on these results based on organizational characteristics. There was a slightly higher tendency for financial health at the top of the budget spectrum ($20 million and above), and a slightly lower tendency at the bottom ($150,000 to $250,000). We found that organizations with an audience-driven, performance-based focus were more likely to be weaker, while art and natural history museums were more likely to be stronger. A particularly disturbing finding was the high percentage of organizations currently in capital campaign seeking to embark on major expansions that had weak capitalization structures.

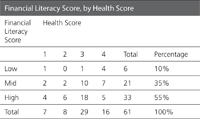

Strong financial literacy. Belying the belief of most academic experts that nonprofit managers do not understand their financial situations, TDC found that organizational leaders were generally articulate about the financial health of their organizations and the strengths and challenges they have faced and continue to confront. Only 10 percent of those interviewed fell into the low financial literacy category, and over half were highly knowledgeable. Financial literacy did not vary significantly by budget size, discipline, or financial health. The majority of those in the weaker financial health categories had mid to high financial literacy scores.

Strong support for capacity building and strategic planning. Philadelphia has the good fortune to have a robust system of resources and incentives to support capacity building that has been built up by regional funders and service providers.

So, why is it that financial literacy and a strong support system do not seem to impact long-term financial health? In TDC’s interviews and in our review of the data, it is clear that many organizations have greatly improved their internal understanding of how to balance their yearly budgets.

There are many incentives in the system that encourage organizations to break even. While breakeven is an essential goal for achieving adequate capitalization, it is not enough. The focus on breakeven has trained attention on the profit and loss statement, while the balance sheet has been neglected. When the goal is breakeven, there is no avenue through which to build up net assets and capital funds, which can only be accumulated through regular and significant surpluses.

One source of the disconnect may be a narrow scope of planning. Although organizations know that they need a higher degree of capitalization to reach their goals, they are often not realistic in projecting the size of the necessary resources and, moreover, they often don’t size the market to see if strategies to garner these resources are feasible. By including capitalization analysis and external market research, strategic planning could become more effective at helping organizations set feasible goals. Benchmarks are only part of the answer, however. Several organizations who had used PACDP data to compare themselves to others commented, “Well, I don’t look too bad compared to my sister organizations.” This type of comparison may have unanticipated consequences for the field. If the majority of your peer organizations are severely undercapitalized and posting only modest margins, what impetus does this offer to change behaviors? As one organization’s director stated, “I know I don’t have enough cash to do anything but no one else does either. Maybe it’s just the way it is. And that’s what my treasurer thought when I showed him some benchmarks.”

Another problem is miscommunication and fear of failure. Many organizations know they are inadequately capitalized and yet feel they have no choice but to assume the risks associated with undercapitalization because they believe that key constituents—including foundations, donors, and boards—do not see this as a prime concern.

For example, a common capitalization challenge is the long-term care and feeding of facilities. The problem is often baked into facilities projects from the start. Many of those we interviewed had compromised campaign goals by decreasing the amount set aside for reserves, capital replacement funds, and endowment. A truly comprehensive look at how much capital may be needed beyond the hard costs—such as tweaking or revamping of newly launched products, new branding or marketing messages that last beyond launch, unanticipated operating costs, or unanticipated capital costs—is often lacking. Again, when pushed on these issues, most managers realize the dangers of undercapitalization but are “afraid if we kept hammering on these issues the project would not move forward.”

These compromises are played out as an organization lives with a new facility. The majority of organizations with facilities reported an inability to generate enough annual surplus to fund true capital replacement reserves. Even those that budget for depreciation do not always use the excess funds to address long-term capital needs. Boards and staff are fatigued enough from trying to achieve breakeven; adding the burden of capital reserves feels impossible, especially given the limited set of funding vehicles. Without addressing facilities needs on an ongoing basis, organizations fall back on capital campaigns to raise funds when needs become pressing. While there may be some efficiency to this type of fundraising, there are also significant dangers. A startling finding from this study was that to make these capital campaigns attractive to donors, organizations often plan expansions or remodeling projects that will ultimately increase operating costs, further eroding the organizations’ ability to meet routine facilities needs on an ongoing basis.

Many groups interviewed clearly see the world changing around them. Even those who felt stable expressed an awareness of the tenuous position they occupy, the changing nature of the cultural environment, and their fundamental vulnerability. Many organizations are trying to define a response to the impact of rapid change in audience behavior and the crowded field of cultural opportunities now available in Philadelphia. For many the lack of access to risk or working capital stymies their ability to fully define the problem—is it a marketing issue, a product problem, or a question of relevance to mission?—and then respond to the problem in a meaningful or creative way. As one organization’s director stated, “I feel as if the arts world is at a critical moment when we need to take some real risks. Yet somehow there is an overall feeling that art groups need to be financially conservative. There is not much reward to taking risks unless you succeed every time—which, of course, is not the nature of risk.”

How Can the System Move Forward?

In TDC’s view there are three things that appear to advance capitalization:

- Financial literacy that affords managers and boards an understanding of the organization’s financial structure.

- Robust strategic business planning that establishes a feasible roadmap to sustainability.

- Incentives from boards and funders that recognize and support the results of robust planning and a common language through which to have an informed discussion about capital needs.

While we found that most organizations can identify their key capitalization issues, they have not been able to integrate this knowledge into coherent plans that tie to a comprehensive and contextual strategy.

As we spoke with organizational leaders, we heard that trustees often are not focused on capitalization and that funders often do not offer rewards and incentives that foster healthy capital structures. The incentives that funders currently do provide do not go far enough. If organizations are not asked for evidence of an integrated capitalization strategy, they fall back to a balanced budget stance, since this is already difficult enough to achieve. Many of the organizations we spoke with were afraid to talk to funders and donors about undercapitalization because they worry about being perceived as weak and, ultimately, “unfundable.”

Talking about capitalization in the current economic climate is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it opens up the conversation about financial health—there is no shame in claiming fragility in these troubled times. On the other hand, TDC worries that the economic crisis will provide yet another excuse to duck the hard questions. Depending on the soundness of an organization’s capital structure and the quality of the board and management, the recession means something very different for different organizations. For one group, this is the rainy day for which they have prudently prepared. They have options. While belt-tightening will be painful, it won’t change the fact that they will make it through the downturn with their core missions intact. For a second group, the recession will have a profound impact on an organization’s growth and development. For those in the middle of a lifecycle change, the economic downturn increases the risk factor tremendously. For those facing the decision to grow or change, they may have to forego their dreams until conditions are more favorable, perhaps sacrificing long-term strategic positioning for short-term financial health, at least temporarily. For a third group, the recession will be the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Managing structural deficits and fragile balance sheets through the near term will be a more and more monumental task, and the feasible set of options will narrow. For these organizations, everything needs to be on the table, including strategic repositioning, merger, and bankruptcy.

The key question that management, boards, and funders need to ask at this point is: Which of these realities is mine? If the key stakeholders are not in agreement about an organization’s reality, it is impossible to have an honest conversation about workable, effective solutions, and organizations run the risk of a debilitating indecision. If they assume the wrong reality, they may end up making completely inappropriate decisions that do nothing but stave off the day of reckoning a little further. If they can agree on the correct reality, even if it’s ugly, there is a hope of crafting feasible solutions or, in the very least, salvaging the core pieces of value the organization retains.

Excerpted from Getting Beyond Breakeven: A Review of Capitalization Needs and Challenges of Philadelphia-Based Arts and Culture Organizations, by Susan Nelson. The report was made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the William Penn Foundation.

Selected Resources

Elizabeth Keating, “Passion and Purpose: Raising the Fiscal Fitness Bar for Massachusetts Nonprofits” (Boston Foundation, 2008)

Clara Miller, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Understanding Nonprofit Capital Structure” (Nonprofit Quarterly, Spring 2003) and “The Business Roots of Capacity and Mission at Nonprofits” (Nonprofit Finance Fund, 2002)

Susan Nelson and Ann McQueen, “Vital Signs: Metro Boston’s Arts and Cultural Nonprofits 1999 and 2004” (Boston Foundation, 2007)

George Overholser, “Nonprofit Growth Capital: Building Is Not Buying” (Nonprofit Finance Fund) and “Patient Capital: The Next Step Forward?” (Nonprofit Finance Fund)

Jim Rosenberg and Russell Taylor, “Learning from the Community: Effective Financial Management Practices in the Arts” (National Arts Strategies, 2003)

Thomas Wolf, “The Search for Shining Eyes” (Knight Foundation, 2006)

Dennis Young (editor), Financing Nonprofits: Putting Theory into Practice (Altamira Press)

Notes

- TDC interpreted “arts and culture” broadly to include a multitude of disciplines, reaching beyond the traditional fine arts. We sorted organizations into 10 discipline groups: art museums, arts education organizations, arts service organizations, dance organizations, historical museums and societies, humanities organizations, music organizations, natural history and other museums, theaters, and visual arts organizations.

- The organizations were drawn from grantee lists supplied by the William Penn Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts, and were chosen to constitute a representative (but not random) sample. All organizations had budget sizes above $150,000.

- It is of interest to note that these conditions are not unique to the Greater Philadelphia area. The Boston Foundation recently published two reports, “Vital Signs” and “Passion and Purpose,” that reinforce our findings. “Vital Signs” reported very similar financial conditions for a significant segment of the Greater Boston arts and cultural sector. “Passion and Purpose,” which reviews the health of the overall nonprofit sector in Massachusetts, points to the similar weakness in the capital structures of a critical number of organizations regardless of subsector.