The Funder and the Intermediary, in Support of the Artist

A Look at Rationales, Roles, and Relationships

It also emerged that this was an area of philanthropic practice that had been little examined, and about which little had been published. Interviews with funders during the research work also revealed that while a number of foundations were using intermediaries, their practices had independently evolved, and a wide range of methods and procedures were in use.

What follows is the first tangible product of GIA’s Research Initiative on Support for Individual Artists. In her analysis, Claudia Bach provides both an overview of the range of philanthropic practices involving intermediaries and regranters, as well as an exploration of a number of related topics and questions that emerged during the course of this work.

— Tommer Peterson, coeditor

Download:

![]() The Funder and the Intermediary, in Support of the Artist (438 Kb)

The Funder and the Intermediary, in Support of the Artist (438 Kb)

The use of intermediaries by a funder supporting individual artists is . . . (select all that apply):

- a way to access targeted expertise in identifying and selecting artists

- a means of advancing shared strategic priorities

- acknowledgment that working directly with the funder may be problematic for some artists

- a way to experiment and learn

- due to limited internal capacity for working directly with artists

- a legal or tax necessity

- a way to provide interlocking forms of support and services for artists

- all about efficiency

- a form of mitigating risk

- a way to strengthen the artist support ecosystem

Intermediary and regranter have quietly but emphatically become part of the lexicon of arts funding, perhaps nowhere more so than in the area of support for individual artists. This became abundantly clear when GIA and its Individual Artists Support Committee set forth to undertake GIA’s Research Initiative on Support for Individual Artists, an effort to shed clearer and more consistent light on the efforts of organized funders who directly support the work of individual artists. Dollars destined for artists’ grants, residencies, career development, and other forms of support are not easily tracked. This can be true when the funds flow directly from funder to artist and especially when the money is directed to a nonprofit organization that plays the role of intermediary. What occurs downstream between the intermediary organization and the artist remains largely unexamined. This gap has left the arts sector unable to measure, applaud, or decry the state of support intended to reach individual artists and to understand fully the impact and import of intermediaries in the artist support ecosystem.

While some funders work directly with artists, many seek to deliver support to artists by working with intermediaries. Intermediary organizations come in many shapes and sizes, reflecting the variety of organizations, structures, and services that connect to individual artists. Some started from grassroots or artist-generated efforts, others were created as a result of funder initiatives, and some evolved to serve individual artists in addition to other organizational activities. Services provided to artists by intermediaries take many forms, from the regranting of funds to providing career development assistance or space to work. Some intermediaries provide artists with an integrated blend of monetary support and nonmonetary services. A common thread of intermediary organizations is that they connect directly to the artist. The funder, most often, funds a specific program offered via the intermediary. The role of the intermediary has been described as being fundamentally liminal — occupying a position on both sides of a boundary or threshold, a place where relationships with both funders and artists must be continuously navigated with balance and grace.

What is known about the practice of using intermediaries in support of artists? While funders are generally comfortable with the term intermediary, and while spellcheckers will eventually learn the awkward regranter, critical analysis of this practice is scant. Regranting is but one aspect of the growing territory covered by intermediaries. As one funder-turned-intermediary noted, “If you are serving as an intermediary you are not just doing regranting. You have to approach it with purposefulness, providing interlocking pieces. Intermediary practice is so embedded we don’t think about it much.”

There is surprisingly little literature on the role of intermediaries in philanthropy, and even less on the practice as it pertains to support of individual artists. A smattering of articles and reports, some of which remain unpublished, touch on aspects. The most in-depth examinations look at the practice in the context of the larger nonprofit world and focus on defining the tactical and strategic benefits of using intermediaries. An increase in foundations’ use of intermediaries is noted in the 1980s and 1990s following the Ford Foundation’s creation of the Local Initiatives Support Corporation in 1979 (Szanton 2003). A working paper written in 2006 for the Ford Foundation (Atlas and Brunner 2006) examines the importance of intermediaries in working with and supporting diverse constituencies of artists, as does a report commissioned by the Asia Society in 2005 (Whang, Cooper, and Wong 2005). Such concerns with equity in artist support, and in arts support at large, have increased over the past ten years, and conversations today often reference this issue as a backdrop against which intermediaries are seen as important players.

This article does not attempt a scholarly examination of the practice. It offers instead a set of observations and questions based on the information gathered in connection with GIA’s Research Initiative on Support for Individual Artists through numerous interviews and conversations focused on that initiative in 2012 and 2013. The benchmarking efforts continue to make good headway, with the completion of A Proposed National Standard Taxonomy for Reporting Data on Support for Individual Artists in March 2014, which reflects the good thinking of so many in the funding community. The taxonomy opens the door to standardizing and collecting information to advance knowledge and research. It can spur the collection of data for benchmarking practices, identify gaps in the support landscape, or build understanding of trends that may influence new directions. But it will take years before we can see the accumulation of those data. The topic of intermediaries and regranting emerged through the research process as worthy of more immediate examination and further conversation. There is no impediment to focusing thought and dialogue on the practice of using intermediaries here and now, while we await system-wide data collection.

To Use or Not to Use an Intermediary: Key Reasons Funders Work with Intermediaries

Any discussion of funders and intermediaries working together to support artists must acknowledge the gratitude and respect with which most funders speak about intermediaries, and likewise the appreciation intermediaries have for the vast majority of funders. The value intermediaries bring to the ecosystem of artists support is considered essential by many funders who support individual artists. There is an appreciation for the challenges and vulnerability of these organizations, and for the day-to-day heavy lifting undertaken within constrained resources. And intermediaries speak of the critical synergy that so many funders bring to their work.

For some funders it is a long-standing practice. The McKnight Foundation, for example, has successfully worked with intermediaries for more than thirty years. A number of funders and intermediaries note that the growth of this practice was, in part, a result of the retrenchment of support for individual artists by the National Endowment for the Arts brought on by the culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s. The resulting funding climate and the reduction of resources were catalytic for exploring ways to cut costs and, in some cases, the need for more distance from the selection and support of artists creating potentially controversial work. Some intermediaries, such as the National Dance Project or the National Performance Network, were born through the efforts of one or more funders who identified a void in artist support and sought to create a systemic intervention. Others point to the more recent financial crisis of 2008 as an impetus for some funders to explore the use of intermediaries. A venture capital mind-set aligned with dot-com industries is credited by some as leading funders toward intermediaries by causing a shift in philanthropic strategy. This view sees increased interest in providing broader support for an artist’s overall career development rather than simply writing a check, and holds that intermediaries are often best suited to this mix.

Data from interviews with funders and intermediaries suggest six pathways to bringing funders and intermediaries together that warrant more examination: expertise and networks; logistics and administration; structural or legal concerns; philosophical rationales; extending value beyond monetary support; and strengthening the field or ecosystem of artist support. Some pathways start from a position of the funder needing help to carry out its philanthropic work with artists, while others start from a desire to strategically assist in strengthening an artistic discipline or parts of the field.

- Funders often seek intermediaries for their expertise and networks in an artistic discipline and their on-the-ground relationships with artists. They may be intermediaries familiar with artists working in a particular art form or field, artists living in a specific geographic region, or those artists who identify with a specific ethnic or cultural community. Deep knowledge of the world of playwrights, the needs of printmakers in rural areas, or the nuances of culturally specific dance traditions is not something most funders claim. An intermediary is likely to bring insights and perspectives unavailable to the funder. From intimate connections within a subculture to a national perspective on an artistic practice, intermediaries are often steeped in specifics and nuance.

- An initial impetus for connecting may be issues of logistical and administrative capacity. A small foundation staff may have limited ability to take on paperwork and processes or to dive into the complexity of running one or more artist selection processes. With systems already in place, an intermediary may be able to extend the funder’s bandwidth and create efficiencies in distribution of dollars. The Alliance of Artists Communities, for example, plays this role for a number of foundations around the country, as well as for a state arts council. Selection of individual artists remains largely based on the use of peer panels, and intermediaries have fine-tuned the mechanics and subtleties of this widely used process. Conducting effective and respected selection processes builds on the same expertise and networks noted above, and then carries over into the delivery of artist services by the intermediary.

- A funder may require ways to mitigate risk, seeking “arm’s length” control while supporting artists. Funders’ structural or legal concerns may be as straightforward as a legal charter that prohibits giving funds directly to individuals or may reflect legislated requirements for handling state funds. An intermediary can often be more accommodating and adaptive than a funder in assisting individual artists in a more personalized fashion, and is often able to work more flexibly with artists’ collectives or other configurations. For some funders there are concerns about distancing a selection process from a living donor. When a living artist is the donor there may be the legal risk of support appearing to be tainted by the potential of “private benefit” to the donor-artist. This was one consideration that led the Dale and Leslie Chihuly Foundation to work with Artist Trust for management of its Arts Innovator Award. The political minefields that some funders, especially public funders, must traverse are lingering artifacts of the culture wars.

- For some funders the use of intermediaries is grounded in a philosophical rationale. This may be clearly delineated in a funder’s mission statement but more often reflects an outlook or desire to stretch the boundaries of the foundation’s work. A number of funders articulate a fundamental belief in the value of working with entities with strong ties to individuals in specific communities. The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, for example, identified eighteen organizations that serve this function as the foundation’s Performing Arts Regranting Partners, and the McKnight Foundation’s giving strategy is built on working with a network of arts councils and organizations closely tied to local communities or specific artistic disciplines. Intermediaries are seen as essential players in building more diverse and democratic dimensions for the distribution of resources to artists. Identifying intermediaries who share the strategic priorities of the funder is crucial in carrying out this work.

- A primary reason funders look to intermediaries is the unique way in which many intermediary organizations straddle the worlds of monetary and nonmonetary support for artists. Funders are enthusiastic about extending the value of financial support through the connections, networks, training, and ongoing relationships with artists that intermediaries can offer. The Doris Duke Charitable Foundation is working with Creative Capital for such reasons in delivering the Doris Duke Performing Artist Initiative. The interweaving of dollars with direct artist services is something that few funders see as their purview. Combining money with a package of related resources and services appears to be of growing interest in the field, both to artists and funders.

- A number of funders expressly intend to spur field building through their work with intermediaries. This may be through connecting or strengthening, or in some cases creating, a cohort of intermediaries to address identified needs or gaps in individual artist support. Creating consortia of intermediaries, such as those brought together as part of the ten-year Leveraging Investments in Creativity (LINC) initiative, can accelerate learning and impact. Peer-to-peer exchange benefits individuals and organizations, and stimulates the larger field. A consortium of funders also may benefit from working together, as occurred with the forming of United States Artists in 2005 to create a new entity for artist support. Other funders hope to strategically support the health and development of existing arts service organizations that they see as critical to the field or a geographic region. At an informal level, many funders note that they hope their relationship with an intermediary serves as a useful resource, with the intermediary having access to a funder’s knowledge and perspective from the larger field.

Fortunately, representatives of intermediary organizations who were interviewed for this article see the benefits they bring to the relationship with funders in a similar light. Being close to the ground, they really understand culturally specific contexts, as well as norms and needs that can be made less visible or distorted by the power dynamic of the funder’s role. Being trusted by artists is central to their success and is of critical value to funders. The ability of some intermediaries to aggregate funds for investment in individual artists puts them in a position to leverage funds and provide artist services at a different scale.

This unique outsider/insider role can be fraught, as intermediary organizations must continually balance their credibility as insiders while representing the resources of others. Intermediaries can be conduits of truth telling to foundations when communication channels are open enough to permit them to share what they have learned through their more dimensional relationships with artists. Intermediaries may be able to convey information that individual grant recipients can’t or won’t. The Alliance for California Traditional Arts, for example, works with many artists who have not had access to arts philanthropy. Their program staff is able to collect and distill comments and experiences to share with funders. Intermediaries are being paid by funders to be really good at what they do as regranters, but are often called on as colleagues and thought partners, taking positions based on having their ears to the ground.

Observations on Funder and Intermediary Relationships

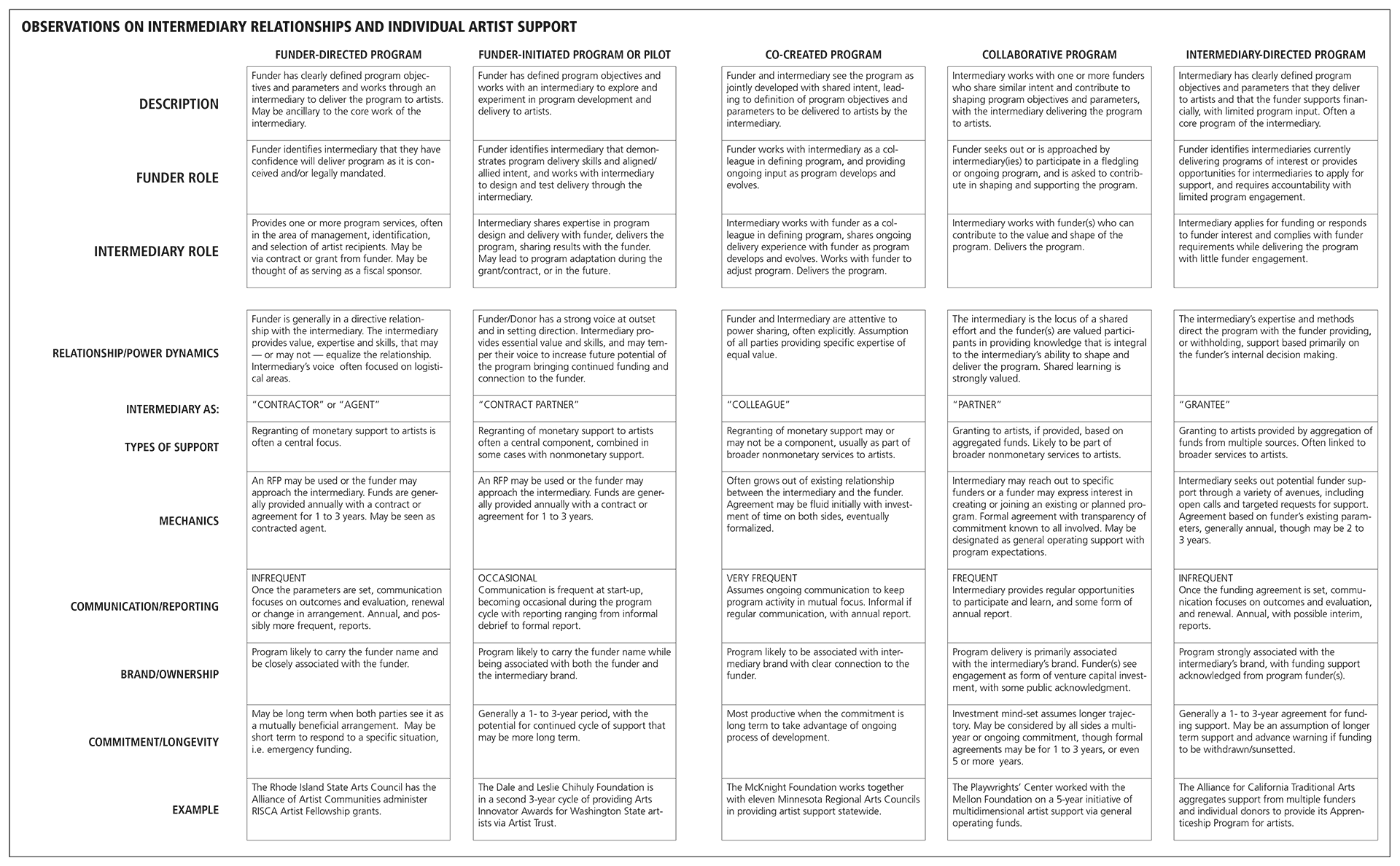

The chart below identifies key dimensions of the funder/intermediary relationship, and hypothesizes five archetypes. It offers a way to consider the various modes in which funders and intermediaries work together to support individual artists. The categories are intended to provoke thinking about the practice of using intermediaries, while keeping in mind that they exist on a continuum, with hybrid mixes being common. Additional research is needed to examine these practices more rigorously and further refine the model. Future investigation can introduce more consistent terminology and provide a deeper look at practices that shape these relationships. Until such research is available, however, funders and intermediaries may find value in considering the range of relationships described in the five archetypes.

Building and Balancing: Making a Working Relationship

In early phases of the funder/intermediary relationship both parties seek to meld mission, desire, and opportunity into a workable form. The creation of a symbiotic relationship, however, is often challenged by power dynamics. The funder holds the reins on a fundamental resource — money — while the intermediary brings knowledge, skills, and/or constituent access to the relationship. Like any relationship navigated by human beings, there is an exploratory phase of learning the strengths, vulnerabilities, and limitations of each party and assessing whether working together will yield more than the sum of the individual parts. Will this be a long-term relationship or more like a one-night stand?

So much in a relationship depends on the dynamics of power. Questions of control, whether explicit or implicit, undergird all the dimensions noted in the chart. The power that comes with holding the purse strings can be significant, but in most cases this is modulated by sincere appreciation for the work and expertise of intermediary organizations. Respectful and professional behaviors are found in abundance across the categories, but that does not diminish the fact that there are significant differences across the spectrum. The character of a funder/intermediary relationship is often influenced by how it was initiated. These relationships continue to evolve, yet the power dynamic is often built on the groundwork of how the two parties first engage, and the way they establish their roles.

A commitment to high-quality communication is at the heart of effective funder/intermediary relationships. Continuous dialogue throughout the year, and not just at the end of a project, allows both sides to disclose what is really happening. This creates the kind of transparency that permits all involved to explore failure together and adjust tactics to achieve the best outcomes. “Authentic two-way communication” is how one intermediary neatly summed up this dynamic.

The analogy of parenting was used by a number of interviewees when discussing roles, though this analogy sits uncomfortably for some funders and intermediaries. There is the potential for such analogies to harbor condescension, even where none is intended. One funder noted there are many charitable giving styles, some more benevolent, some more hierarchical, some characterized by inflexibility, and others more collaborative or nurturing. Funders often have clear and fairly fixed ideas about their charitable intent, as is their prerogative, yet, “a wise donor needs to leave enough flexibility to carry out the intent.” Intermediaries can be and often are encouraged to push back and challenge the assumptions of funders, while still acknowledging that one party holds the financial power. Intermediaries can be very attuned to the complexity of this power dynamic since they, in turn, take on the funder role when they distribute funds or services to individual artists. “As an intermediary you are parented and then become a parent in the same project,” pointed out a longtime executive director. The tone and delivery of communication can make the difference between offering support and feedback, and appearing to be overbearing and controlling. One must keep in mind the value that all parties bring to the table.

The relationship between funder and intermediary can provide a kind of mutual safety net. Having multiple parties paying attention can ensure that work is carried out with integrity and excellence, and that challenges are addressed in a timely fashion. In some cases, funders review and sign off on finalists or grantees. This can help funders avoid unintended double funding of individual grantees through multiple grant programs, or the awarding of grants to troubled organizations when artists’ support is for partnership with a nonprofit. Review by funders can also guard against conflicts of interest and can satisfy the foundations’ auditors that they are practicing due diligence. Other funders consider distance from the selection and award process to be an essential aspect of working with an intermediary. Entrusting funds to another entity always involves some risk. Funders as well as intermediaries are aware that this is a financial relationship that requires clarity and controls. Expectations and abilities can be unbalanced, especially when a funder is dealing with a small organization with cash flow issues or when overhead expenses have not been realistically assessed. One funder shared a cautionary note on the challenges of exerting appropriate levels of control to safeguard the funds entrusted to an intermediary. The financial fragility of some intermediary organizations, especially smaller organizations, may not be obvious, and funds intended for regranting can mask the true financial picture. It can be difficult for a funder to be sure that the organization’s board of directors is overseeing the situation effectively without seeming to exert intrusive control. Finding a balance of adequate information and independence can be challenging.

The issue of ownership and control can also be considered through the lens of branding. For some funders there is a strong desire to have the name of the funder clearly associated with a program of artist support. This tends to be linked to situations where a funder is directive in defining program parameters. The influence of a single funder appears to diminish as the brand of the intermediary becomes more prominent, especially in cases where the intermediary aggregates funds from multiple funders. For some funders this is welcome; others seek to retain brand association.

Changes in staffing on either side can destabilize and threaten an otherwise healthy relationship. It is easy to underestimate the importance of a strong relationship between specific individuals. There is no monetary value that can be placed on the trust and understanding built over time. Relationships and programs that have stood this test of time, with ongoing adjustments and change, are deeply valued by all involved. Institutional relationships have many facets and extend beyond the personal link between funder and intermediary program managers, yet individuals are often noted as the glue that connects and propels successful intermediary relationships. Relationship longevity is understood to provide benefits not only to funders and intermediaries but also to artists.

Characteristics of Good Practice

The funders and intermediaries interviewed had much to say about practices that are likely to yield a highly productive relationship. Many of the characteristics are interdependent and build on the areas outlined above.

Self-evident is the most fundamental practice: the development of trust by all parties involved. This is closely tied to the vital need for funder confidence in the ability of the intermediary, and belief in the consistent quality of the intermediary’s work. The corollary to this, of course, is the intermediary’s consistent delivery of work worthy of this trust and confidence.

Funders that take the time to understand the essential DNA of their intermediaries are best positioned to be seen as colleagues and partners. It is very helpful when funders have a deep understanding or at least appreciation of the complexity and effort involved in running a grant selection process, delivering career support, or doing work with specific artist constituencies. Some intermediaries feel that funders don’t truly understand and appreciate what they do for them. Intermediaries that employ rigor in evaluating their work, regularly collect data, and can speak with clarity about outcomes open the door to greater understanding by funders who value those forms of measurement.

Funders are generally eager to share their knowledge and offer a perspective from their perch in the field. Letting an intermediary know that such sharing is not intended to be directive can be tricky. A funder who is able to listen, observe, and share without being directive — or be directive but still listen — is considered a fine colleague.

Flexibility is a prized practice. Funders who permit and accentuate flexibility in program delivery appear to have the most productive relationships with intermediaries. An attitude that says “we are here for you” permits intermediaries to be most responsive to the artists they work with. Being there for the intermediary may be as practical as providing a space for conducting a panel or may take the most coveted form of flexibility: general operating support.

A funder that provides general operating support — either intended for artist support or in addition to program funding — indicates strong confidence that the intermediary will use the funds wisely, without the more constraining elements of program support. Operating support affirms and acknowledges the larger work of the organization. The flexibility inherent in such support is especially well suited to the evolution of new program initiatives. An emerging practice in this realm can be seen in the Mellon Foundation’s support to the Playwrights’ Center in Minneapolis. The Playwrights’ Center explicitly requested that a five-year initiative of individual artist support be provided as general operating support. Specific programs were initially defined, but based on artist feedback and experience (and in consultation with the funder), some programs morphed. The intent and purpose of artist support never wavered, but the flexible framework of general operating support, aided by ongoing dialogue between the intermediary and the funder, permitted a more adaptive approach to program design and delivery.

Duration and consistency of support over time have a critical impact on program strength, the vigor of program outcomes, and the health and well-being of an intermediary. A number of intermediaries noted that it takes five or even ten years for many programs to be fully formed and show their true value. Current practice reflects a move toward three-year funding cycles. While intermediaries are grateful to get beyond a one- or two-year cycle, many speak to the benefits of longer-term support in building and delivering artist support programs. Some funders are seen to have “funder ADD,” wanting to fund new and “piloty” programs, and are not there for the longer haul, even though it takes years for a new program to be truly established. Innovation in program design can be fetishized to the detriment of the core work of getting money to artists to do their work, as Todd London explored in a talk at the National Innovation Summit for Arts + Culture in 2013 (London 2013). Many intermediaries have spent years developing and honing core programs in response to the needs of individual artists. These programs can struggle to compete for funder support against the flash and sparkle of new pilot programs. The termination of a long-term funding program can pull the rug out from under an intermediary and its core programs. And when funder support is withdrawn it is the intermediary that is likely to directly experience the frustration and anger of artists. Providing sunset grants is a practice that helps to minimize such destabilization and preserve relationships for the future.

Overhead costs can be a sticking point in funder/intermediary relationships: funders need to be aware of the true costs of carrying out the work, and intermediaries need to be clear on the financial realities. Some intermediaries feel confident that these costs are appropriately covered as part of the overall project or program budget. Others are paid a flat fee to provide regranting or other services. Current practice trends toward paying fees of approximately 5 percent to 10 percent of program funding, though fees may reach 15 percent. Some intermediaries noted that the added time and effort needed for working with some artist constituencies, or for making many small grants, are not well acknowledged and often underfunded. This can include intermediaries working to build or sustain relationships with artists based on geography, cultural and language differences, and differing degrees of experience with institutional funding. One funder noted that the true cost of building and supporting relationships with such artists can account for more than 50 percent of the budget of running a regranting program, especially when grants are for small amounts. No one likes to think that intermediaries are being nickeled-and-dimed, yet some intermediaries find themselves picking up costs that are tied to a funder-defined program. Overhead issues loom particularly large in small organizations where cash flow is a constant concern. According to one intermediary, funders need to “take good care of the intermediary so that we can take good care of artists.”

The way that a foundation program manager makes the work of intermediaries visible to foundation leadership may not be visible to the intermediaries, but can have many implications. The funds for individual artist support are often modest and seen as being more complicated with less measurable impact than funds for organizations. The practice of actively sharing the good work of intermediaries and the impact of individual artist support programs helps tie this work to the larger work of the foundation.

Intermediaries and funders are both in a position to leverage the relationships and knowledge that grow from their mutual work. Using the networks and connections of either party can greatly expand ideas and experiences for work within, or beyond, the program that brought the two together. These relationships can open the door to a more expansive pool of potential panelists, advisors, and thought partners.

Other Pathways to Artists

There are good reasons why a funder of individual artists may eschew or make very limited use of intermediaries. For funders like the Leeway Foundation, the direct relationship to the artist is at the core of their mission, and their engagement with individual artists is seen as central to their work. For others, including the Joan Mitchell Foundation, it is an extremely meaningful dimension of their work, and their internal management of direct support programs ensures that they are viscerally involved with and attentive to the delivery and impact of their support.

New models explore other dimensions of the ecosystem for artist support and may suggest that galleries and museums can play a kind of intermediary role. The New Foundation Seattle, whose mission is to encourage the production of contemporary visual art in Seattle, has developed its Acquisition Program, an initiative that seeks to make the work of Seattle-based artists accessible to interested museums and curators throughout the United States. The foundation works with a small cohort of visual artists selected by a nomination process with the intent of working with these artists over a long period of time, placing multiple works in multiple museums or providing exhibition support. Artists receive assistance at critical stages of their creative lives. Artists must have gallery representation, and the artists, as well as the galleries, benefit financially from purchases and exposure. Curators also benefit as signature works by these artists are added to museum collections from the exhibitions they curate, or projects they organize. Cohort artists receive other types of support, such as access to networks and visiting curators, and the option to apply for a grant for travel out-of-state for self-directed, self-organized professional development. The foundation’s donor and founding director have a well-articulated interest in controlling the evolution of this philanthropic experiment while staying committed to a core purpose of supporting a small and slowly growing cohort of artists throughout their careers. In an era where funding has been drastically cut for museums’ acquisition and travel budgets, the foundation hopes to keep Seattle’s artists on the national radar by providing financial assistance, enhancing visibility, and incentivizing curators to work with them.

Crowd-sourced funding can also be construed as an emerging intermediary function, especially in cases where an organization, such as 3Arts Artist Projects, plays the role of intermediary by identifying artists for support through a crowdfunding platform. A foundation funder may then support and leverage the giving mechanism, as does the Joyce Foundation by providing matching funds with 3Arts Artist Projects. Such funding ultimately relies on charitable contributions from individuals rather than foundations and warrants its own examination beyond the scope of this article.

Questions and Crystal Balls

The essential importance and contribution of individual artists appear to be in a phase of renewed consideration in the arts sector. Along with this comes the attendant exploration of ways to support artists. Relationships between funders and intermediaries are likely to continue to be an important dimension of this, and may well multiply. The next step in GIA’s Research Initiative on Support for Individual Artists will be the forthcoming A Proposed National Standard Taxonomy for Reporting Data on Support for Individual Artists that provides a framework for identifying funders working with intermediaries to deliver support to individual artists and will eventually permit the collection of data at multiple levels. This will allow deeper investigation of funders’ intentions in supporting individual artists, the extent of funders’ use of intermediaries, the scope and scale of programs delivered by intermediaries, and the types of awards and resources that are distributed to artist recipients. Any one of these levels will provide a picture that we currently do not have, and together, over time, can offer tools to help shape the decisions of funders and intermediary organizations.

Against this backdrop, the following questions are posed for additional dialogue and research as the field develops a more nuanced understanding of the ways that funders and intermediaries work together:

- How can the work of intermediaries better inform and shape individual artist funding practice?

Are intermediaries gathering and delivering enough feedback about their work and from artist recipients to help funders shape responsive funding practice? What resources are needed by intermediaries to better gather and report this information? What conversations are needed among funders to examine and institute timely change? What evaluation methodologies best serve the needs of the artist and the intermediary, as well as those of the original funder? What standards might simplify this process as well as generate some consistent data across the field? When does authentic conversation trump data collection?

- How can funders work with intermediaries to best reflect and respond to changes in definitions, demographics, and art practice?

As discussions about artistic quality shift and become more strategic and less discipline based, are the right intermediaries being used? The definition of artist is changing in the field (Markusen 2013), and this may require that funders build new relationships with organizations that are not currently playing an intermediary role. Is the role of the intermediary different when supporting socially engaged or socially involved work? Are funders approaching culturally appropriate organizations when seeking to support specific artist constituencies, or do such organizations too often fall outside the circle of known players? How can the field make sure that cultural equity is enhanced by connecting funders and appropriate intermediaries to reach diverse artists?

- Is there a need to codify “best practices” for funders and intermediaries engaged in this work?

What standards of practice, if any, are most desired by funders? By intermediaries? Would it help artists if intermediaries instituted more shared standards of practice, such as tools or guidelines for contracting with artists? Might this make it easier for a broader range of organizations to successfully play the role of intermediary and bring access to new constituencies of artists? How can “true” overhead costs be better understood and addressed, moving beyond ratios to quantify the value of regranting? When is funder intervention with an intermediary warranted or beneficial for program success?

- What impact do structural issues have on delivering artist support from funders and intermediaries?

What is the best pathway to artists when a funder believes no existing intermediary meets an identified need? When funders create a cohort of intermediaries, does such a structure create stability and commitment, or does it inhibit change in artist funding practice? Do such funding interventions cause stasis or encourage change in the work of the intermediaries or the work of the funder? Do certain kinds of funders, such as family foundations, tend to have a more directive voice in shaping artist support programs with intermediaries?

How key are intermediaries to the future of individual artist support? The practice continues to be central to supporting artists, although there is a dearth of research on the topic. Funders and intermediaries will benefit from entering into, developing, and even ending such relationships, with a clearer understanding of the dynamics of this way of working. The potentials and pitfalls of this relationship are still not well understood, though it is clear that it fulfills a critical and multidimensional function. It is likely that there are undocumented impacts that accrue as foundations invest in intermediaries to support individual artists. All parties seek to find the best ways to serve the interests of artists while being true to their respective missions. A strong and resilient ecosystem of artist support benefits all, and intermediaries are likely to play an enduring role.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Alan Brown and John Carnwath of WolfBrown for their essential contributions to this article, and to Tommer Peterson and the GIA Individual Artists Support Committee for instigating and advancing this work examining individual artist support.

Generous and frank conversations and interviews were held with more people than can be thanked here. Deep gratitude to those individuals who were willing to share their thoughts in a series of interviews in fall 2013: Vickie Benson, Arleta Little, and Sarah Lovan, McKnight Foundation; Jeremy Cohen, Playwrights’ Center; Barbara Schaffer Bacon and Pam Korza, Animating Democracy; Caitlin Strokosch, Alliance of Artists Communities; Cheryl Ikemiya, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; Ruby Lerner and Sean Elwood, Creative Capital; Shari Behnke, New Foundation Seattle; Michael Tobiason, Dale and Leslie Chihuly Foundation; Amy Kitchener, Alliance for California Traditional Arts; Jenifer Lawless, Massachusetts Cultural Council; Cora Mirikitani, Center for Cultural Innovation; Ryan Stubbs, National Assembly of State Arts Agencies; Margit Rankin, Artist Trust; and John McGuirk, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. The comments of participants at GIA’s 2013 Artist Support Preconference also informed this article. Many thanks to Ted Berger, Cindy Gehrig, and Holly Sidford for their long-standing leadership on the topic of support for artists.