The Charitable Deduction

What Does “Tax Reform” Mean for the Arts?

In America, the arts are highly dependent on donations from individuals for funding. Once a new president is in office in 2017, Congress is expected to take up “tax reform” in a serious way.1 How might that affect the long-standing deduction for charitable contributions, and by extension, giving to the arts?

Giving in America

Americans made $17.5 billion in donations to nonprofit organizations in the arts, culture, and humanities in 2014, which constituted nearly 5 percent of all charitable giving.2 Overall, charitable donations have been on the rise in recent years and are finally above prerecession levels. Arts giving alone grew by more than 9 percent from 2013 (7.2 percent when adjusted for inflation).

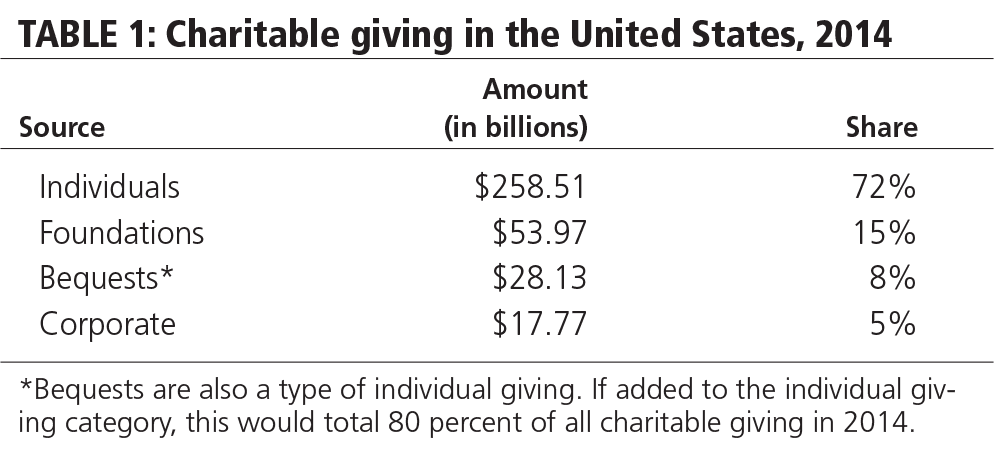

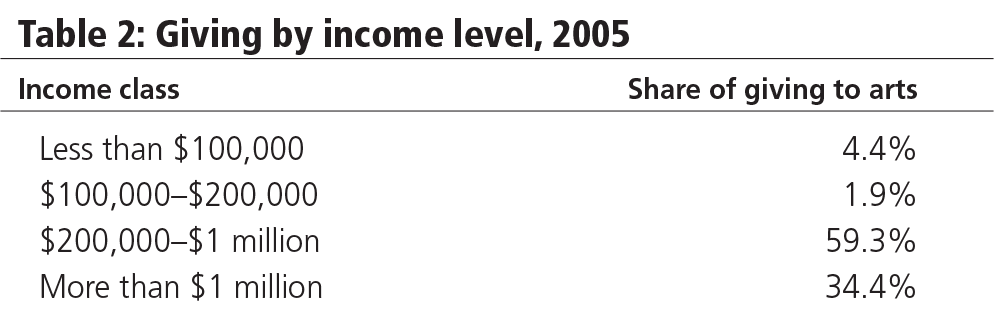

Charitable giving in the United States totaled $358.4 billion dollars in 2014. Nearly three-quarters of that came from individuals, as table 1 shows. The arts receive nearly 60 percent of all donations from people earning between $200,000 to $1 million per year, more than from those in the highest income group (see table 2).3

While arts, culture, and humanities organizations are the fifth largest recipient of charitable donations, they are more reliant on private contributions as a share of total revenue than hospitals, educational institutions, or human service organizations.4 Any changes to tax laws that affect individual giving will have an impact on arts and culture. Exactly how? Estimating the answer lies somewhere between math and policy, and it requires a healthy dose of conjecture.

History and Context

“Tax reform” is a perennial issue in Congress, and it is expected to reemerge in 2017. The Tax Reform Act of 2014, the most recent major tax bill to be debated, is considered a likely model for future legislation. The act includes a provision that could have profound impact on charitable giving. To fully understand it, a little history and context about the charitable deduction is helpful. The US model of funding public goods and services like the arts has a uniquely American ethos.

The personal income tax was established in the United States in 1913. Four years later, concerned that income taxes might discourage or reduce private giving, Congress enacted the charitable contribution deduction as part of the War Revenue Act of 1917.5 For every dollar donated to a charitable cause, the federal government would forgo some amount of tax revenue. Individuals and corporations could take charitable deductions, as could estates.

This model has been seen as consonant with American values, as it allows individual citizens to determine what organizations and activities the government funds, in the indirect form of forgone tax revenues. It is also a continuation of America’s historical reliance on private charities instead of government to provide many public goods and services.

The charitable deduction is not without its detractors, though. Three main issues have been raised: cost, fairness, and effectiveness.

Each year the federal government forgoes significant revenues in this effort to promote charitable giving. The deduction is estimated to have cost the federal government a total of $230 billion between 2010 and 2014.6 Some argue this is too much tax revenue for the federal government to give up.

In addition, the charitable deduction gives greater benefit — and potentially greater voice — to the wealthy. Between 70 and 80 percent of Americans take the standard deduction on their taxes, meaning that any charitable donations they make do not translate into deductions on their income taxes. That means only 20 to 30 percent of Americans benefit. Even among those who do itemize, the wealthiest benefit more because the deduction is based on their tax bracket. A person in the 15 percent tax bracket will get a $15 tax deduction for a $100 donation, while a person in the 33 percent tax bracket gets a $33 write-off for the same donation.

As a result, it is argued, the wealthiest have the greatest impact on how forgone tax revenues are spent. Furthermore, this may encourage nonprofits to alter their work to appeal to the interests and tastes of the wealthiest.

Finally, there is some question as to how effective the charitable deduction is at achieving its goal of increasing private donations. Research seeking to measure the strength of the effect of the deduction has been inconclusive. There is some evidence higher-income donors are more sensitive to the size of their deduction than donors at lower income levels. Other research suggests donations to churches and educational organizations are less sensitive to the amount of the deduction.7 In other words, if the charitable deduction were reduced in any way, it might lead to lower deductions from high-income donors but might have less impact on giving to churches and educational organizations.

Potential Changes to the Charitable Deduction

There have been several proposals in recent years to change the charitable deduction, with the aims of either reducing the cost, making the benefits more equitable, or making it more effective in encouraging greater giving. The first category focuses on the impact of the deduction on government, while the second two categories focus on its impact on those who give.

Proposals to “reform” the charitable deduction are generally one of four types (or a mix of them):

- Caps that limit the size of the tax benefit for individual donors

- Floors that allow deductions only for total giving above a certain amount

- Credits that turn what is now a variable percentage deduction based on income into a flat percentage that is the same for all taxpayers

- Grants where the government matches a donation from an individual with a grant directly to the same organization

Economists have built mathematical models to test the impact of each of these proposals, but because the size of the effect of the deduction on giving is uncertain, no clear predictions have emerged.8 In general, it appears that any proposals that reduce government losses also translate into reduced charitable giving overall, though the effect varies by the taxpayer’s income level.

For example, the Tax Reform Act of 2014 included a 2 percent adjusted gross income (AGI) floor on deductible charitable contributions. The primary purpose of this floor was to reduce costs to the government. When economists at the Urban Institute–Brookings Tax Policy Center tested a similar but smaller, 1 percent floor, they found it increased government income by $10.5 million but reduced charitable giving by between $1.4 and $2.4 billion.9 While the floor led to a reduction in giving among the wealthiest 20 percent of Americans of between 0.9 and 1.6 percent, giving increased by between 0.1 and 0.7 percent for the poorest 20 percent.

This finding for floors generally holds true for caps and credits — giving by the wealthiest decreases, while it holds steady or increases at the lowest income levels.

Potential Impact on Arts Nonprofits

One might draw the conclusion that arts and culture organizations will lose and religious organizations may gain from these proposals. Some research supports this. One set of statistical models found that a 10 percent drop in charitable contributions would lead to an average reduction of 1.5 percent in revenue specifically for arts nonprofits.10 The greatest impact was on organizations with revenues between $25,000 and $500,000.

Care should be taken in drawing conclusions from the limited evidence available. These are simulation models and cannot take into account all the vagaries of human behavior. Still, while the specific size of the impact is not measurable, one message is inescapable: people who care about the arts should stay informed about any efforts in Congress to “reform” the charitable deduction.

NOTES

- My use of quotation marks around the term “reform” is intentional. “Reform” is defined as change that is intended to improve something. However, what one person perceives as an improvement may be seen as the opposite by another. This is as true for the charitable deduction as it is for any public policy.

- Figures on giving are from Giving USA 2014: http://givingusa.org/giving-usa-2015-press-release-giving-usa-americans-donated-an-estimated-358-38-billion-to-charity-in-2014-highest-total-in-reports-60-year-history.

- Roger Colinvaux, Brian Galle and Eugene Steuerle, “Evaluating the Charitable Deduction and Proposed Reforms,” Urban Institute, June 2012; http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412586-Evaluating-the-Charitable-Deduction-and-Proposed-Reforms.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Joint Congressional Committee on Taxation, “Present Law and Background Relating to the Federal Tax Treatment of Charitable Contributions,” February 11, 2013; https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=download&id=4506&chk=4506&no_html=1.

- Congressional Budget Office, “Options for Changing the Tax Treatment of Charitable Giving,” May 2011, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/121xx/doc12167/charitablecontributions.pdf.

- Colinvaux, Galle, and Steuerle, “Evaluating the Charitable Deduction and Proposed Reforms.”

- Charles T. Clotfelter, “Charitable Giving and Tax Policy in the U.S.,” in Charitable Giving and Tax Policy: A Historical and Comparative Perspective, ed. Gabrielle Fack and Camille Landais, 34–62, conference on Altruism and Charitable Giving, Center for Economic Policy Research, Paris School of Economics, May 2012; http://econ.lse.ac.uk/staff/clandais/cgi-bin/Articles/full_volume.pdf.

- Colinvaux, Galle, and Steuerle, “Evaluating the Charitable Deduction and Proposed Reforms.”

- Joseph J. Cordes, “Re-Thinking the Deduction for Charitable Contributions: Evaluating the Effects of Deficit-Reduction Models,” National Tax Journal 64, 4 (December 2011): 1001–24; http://www.ntanet.org/NTJ/64/4/ntj-v64n04p1001-24-thinking-deduction-for-charitable.pdf.