Tools to Support Public Policy Grantmaking

Introduction

Foundations trying to better leverage their influence and improve their impact increasingly are being urged to embrace advocacy and public policy grantmaking as a way to substantially enhance their results and advance their missions. In fact, public policy grantmaking has been described as “one of the most powerful tools available to foundations for creating real change” (Alliance for Justice, 2004, p. 1).

The argument for public policy grantmaking is clear. Achieving large-scale and lasting results for individuals or communities — a goal linked to many foundation missions — typically cannot be accomplished with private resources alone. Often, it requires public investments and government directives. While a foundation might identify effective interventions, for example, and fund their implementation in several communities, larger and more sustainable funding sources are needed to scale up those interventions and broaden their impacts. Securing such commitments requires changes in public policies.

This reasoning is persuasive. Yet to date relatively few foundations have incorporated public policy into their grantmaking agendas. Foundations that make advocacy and policy grants are still considered innovators among their peers.

Various trends, however, are pushing philanthropy farther into the public policy arena. For example, a key barrier to the growth of public policy grantmaking has been a lack of awareness about what private foundations are allowed to do and fund under Internal Revenue Service guidelines. In recent years, a number of nonprofits — such as the Alliance for Justice, the Center for Lobbying in the Public Interest, and others — have worked hard to address this barrier and educate foundations on what is legally permissible in this area. Many private foundations are discovering that they have more latitude with public policy grantmaking than they originally thought and are using a wide range of approaches to engage in the policy process (Arons, 2007; The Atlantic Philanthropies, 2008).

Two Tools to Support Public Policy Grantmaking (.pdf)

Evaluation is another barrier that keeps some foundations from supporting public policy efforts. Advocacy and policy grants can be challenging to assess, particularly using traditional program evaluation techniques, and until recently few resources existed to guide evaluation in this area. In the past several years, however, a number of pioneering foundations, evaluators, and advocates have stepped up to help push the field of advocacy and policy change evaluation forward, supporting the development of practical tools that are grounding the field in useful frameworks and a common language (Coffman, 2009; Harvard Family Research Project, 2007).

Also adding to foundation interest in public policy grantmaking is mounting evidence that philanthropy can play a critical role in advancing policy change that has large-scale benefits for individuals and communities. For example, the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy recently studied the positive impacts of advocacy, community organizing, and civic engagement efforts in both New Mexico and North Carolina. In New Mexico, researchers found that for every dollar invested in the 14 advocacy and organizing groups studied, New Mexico’s residents reaped more than $157 in benefits. That means that the $16.6 million from foundations and other sources to support advocacy efforts totaled more than $2.6 billion of benefits to the broader public (Ranghelli, 2008; Ranghelli & Craig, 2009).

As a result of these trends, there is little doubt that the number of foundations supporting advocacy and policy change efforts has increased in recent years. This article is for foundations that either are interested in advocacy and public policy grantmaking or are involved in it already. It focuses on how foundations can frame, focus, and advance efforts to achieve public policy reforms in their primary program areas. It starts by describing five essential steps for developing public policy strategy and then offers two tools developed specifically to support foundations during the strategy development process.

Five Steps in Developing Public Policy Strategy

Public policy grantmaking requires clear thinking and decisions about the policy goals foundations want to advance, the barriers that stand in the way of those goals, the strategies needed to overcome those barriers, and the roles foundations are willing to play in ensuring strategies succeed. Following is a sequence of five steps and issues to consider when making those decisions.

Choose the Public Policy Goal

Choosing policy goals is the first step in public policy grantmaking. Foundations may be interested in goals that include, for example, a policy’s successful development, its placement on the policy agenda (the list of issues to which decision makers pay serious attention), its adoption by decision makers (or its nonadoption given a potentially harmful proposal), its successful implementation or maintenance once adopted, or its evaluation to ensure that the policy has its intended impacts.

Foundations generally approach goal selection in one of two ways. They can choose their own specific policy goals within their program areas, such as ensuring that a state establishes a specific policy. Or they can choose general policy goals (e.g., reducing ethnic health disparities, improving access to arts education) and then allow grantees to select specific policy targets. Currently, the second approach is more common. However, it comes with a risk. Foundations that design their grantmaking around general policy goals typically support a mix of predefined policy change activities (e.g., media advocacy, leadership development, coalition building). The risk is that those activities may not be relevant or useful for all grantees and the specific policy targets they select. Foundations can mitigate this risk, however, by allowing grantees flexibility when choosing their activities.

Understand the Challenge

After goals are chosen, foundations should assess where issues of interest currently stand in the policy process along with what is blocking their advancement.

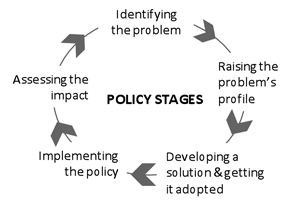

| FIGURE 1. |

|

Figure 1 (Stages of the Policy Cycle) shows a sequence of stages in the policy change cycle (the stages start at the top). Some issues are brand new, and the problems to be addressed have not been clearly articulated or documented. Other issues or problems already are known, but they lack viable policy solutions. Still others have policy solutions in place, but their implementation is problematic. Because policy issues at different points in this cycle will require different strategies, determining where issues are, along with how far they need to advance, is essential.

At the same time, it is important to diagnose why issues are “stuck.” For example, the evidence base documenting existing problems may be insufficient or unconvincing, issues may be perceived as so deep rooted that proposed solutions seem unfeasible, or an organized constituency to advocate for a policy’s adoption may be lacking. An informed assessment of why issues are not advancing will reveal a great deal about the strategies needed to move them forward.

Identify Which Audiences Can Move the Issue

Keeping the barriers to a policy issue’s progress in mind, foundations must decide next who to engage to address them. For example, the national, state, or local media are common audiences. By giving certain topics priority over others, the media can be a strong influence on how the public or decision makers perceive policy issues. Consequently, efforts that attempt to increase an issue’s profile often target the media to increase the issue’s coverage or influence how it is framed.

Responses to this question should be specific. For example, identifying the general public as an audience is too broad. It is much more helpful to identify specific constituencies or segments of the public that are likely to be receptive to advocacy messages and that can influence or inform the policymaking process.

Determine How Far Audiences Must Move

Once target audiences are identified, it is important to assess where those audiences currently are in terms of their engagement as well as how far the strategy needs to move them. For example, audiences may be completely unaware that issues or problems exist.

Alternatively, they might be aware that problems exist but do not see them as important enough to warrant action. Or, even if the willingness to act exists, audiences may not have the necessary skills to advocate. Achieving policy goals may not require driving every audience to act. But because awareness alone rarely drives policy change, strategies that also try to build public or political will or that encourage specific audience action generally are thought to have better chances of success.

Establish What It Will Take to Move Audiences Forward

After assessments are made about target audiences and their engagement, foundations can think about the strategies and activities that can support effective change. Foundations should think broadly about what it will take to achieve their policy goals. This requires thinking beyond just what individual foundations may be able or willing to support; it means thinking comprehensively about what it will take to realize policy targets. Without this approach, foundations may form unrealistic expectations about what their grantmaking dollars can accomplish.

Some strategies will require a broad mix of activities targeting multiple audiences in different ways. Other strategies will be narrow and attempt to move a specific audience in a targeted way (e.g., when an issue is close to a perceived tipping point).

Two Tools to Support Strategy Development

While the previously mentioned steps seem clear enough, navigating them can be a challenge. The policy arena is unique and complex, and public policy grantmaking can be quite different from other types of grantmaking.

This section offers two tools to support foundations as they work through the strategy process. The tools include a visual framework that guides foundation thinking about which public policy strategies to support and a foundation engagement tool that foundation staff members and boards can use when deciding whether to pursue specific grantmaking approaches.

A Visual Framework of Public Policy Strategies

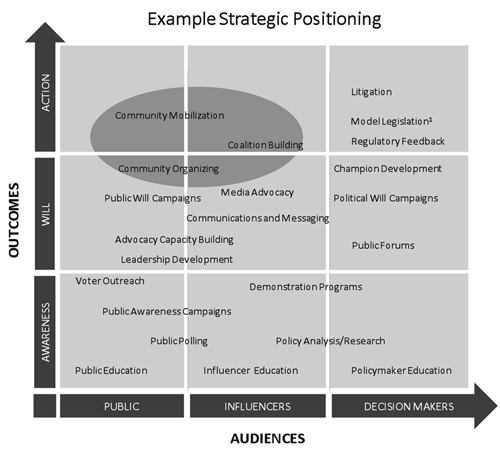

The framework was developed to support steps 3, 4, and 5 in the strategy development process. It helps foundations consider which strategies to fund based on decisions about their audiences and how far those audiences need to move in order to achieve the foundation’s policy goal (Figure 2).

| FIGURE 2. |

|

The framework contains specific types of strategies and activities, organized according to where they fall on two strategic dimensions — the audience targeted (x-axis) and the outcomes desired (y-axis).

Audiences are the groups that policy strategies target and attempt to influence or persuade. They represent the main actors in the policy process and include the public (or specific segments of it), policy influencers (e.g., media, community leaders, the business community, thought leaders, political advisors, etc.), and decision makers (e.g., elected officials, administrators, judges, etc.). These audiences are arrayed along a continuum according to their proximity to actual policy decisions; the farther out they are on the continuum, the closer they are to such decisions. Naturally, decision makers are the closest to such decisions and therefore are on the continuum’s far end. Grantmaking may focus on just one audience or target more than one simultaneously.

Outcomes are the results an advocacy or policy change effort aims for with an audience in order to progress toward a policy goal. The three points on this continuum differ in terms of how far an audience is expected to engage on a policy issue. The continuum starts with basic awareness or knowledge. Here the goal is to make the audience aware that a problem of potential policy solution exists. The next point is will. The goal here is to raise an audience’s willingness to take action on an issue. It goes beyond awareness and tries to convince the audience that the issue is important enough to warrant action and that any actions taken will in fact make a difference. The third point is action. Here, policy efforts actually support or facilitate audience action on an issue. Again, grantmaking may pursue one outcome or more than one simultaneously.

Foundations can use the framework to examine how to position their public policy strategies along these two dimensions. Rather than jumping straight to decisions about which activities to fund (e.g., public awareness campaigns, polling, etc.), the framework encourages foundations to think first about which audiences they need to engage and how hard they need to “push” those audiences toward action.

The shading in Figure 3 (Example Strategic Positioning) illustrates how this might work. The hypothetical policy goal in this example calls for an action-oriented strategy focused primarily at the public or community level. The strategy supports activities that include organizing, coalition building, and mobilization activities to generate the action needed to move the policy issue forward.

| FIGURE 3. |

|

Foundation Engagement Tool

The framework and steps described previously focus on the broad strategic decisions around public policy grantmaking that foundations should consider. Foundations also must consider their specific roles in policy strategies and develop an organizational plan for participating in public policy activity.

Grantmaking strategies to affect public policy raise considerations beyond clarity and alignment on goals, target audiences, paths to success, milestones, and outcomes that are normally considered by foundations when developing a new program strategy. They require assessments of why foundations are uniquely poised to lead or collaborate in specific policy efforts, analyses of potential opposition, the time horizon and staff-intensive nature required for the work, and decisions about whether foundations are prepared to assume the political, reputational, and financial risks that policy strategies demand. These additional issues must be considered and the foundation internally prepared to effectively advance its public policy goals.

In 2008, The James Irvine Foundation held a board retreat on public policy grantmaking in order to deepen board and staff understanding of trends in the field and to discuss how to frame, focus and advance Irvine’s efforts to achieve policy reforms in its core grantmaking programs. As part of the preparation for that board retreat, the Foundation commissioned the development of the steps and framework described earlier. The deliberations at the retreat itself led to the formulation of a tool, developed by Irvine, to facilitate both foundation staff and board engagement at key points in the strategy development and planning process.

The tool contains two parts: (1) primary questions that should be addressed in a strategy paper for the board and that should form the core of any board discussion and (2) secondary questions that staff should explore as part of due diligence and analysis when developing a public policy strategy. Together, these questions help ensure the most strategic decision making by a foundation’s board and staff about whether to pursue a course of action to advance policy reforms.

The tool, presented in Appendices 1 and 2, can be a reference for foundations as they consider their respective roles in the public policy arena and develop plans to execute their strategies. Above all, the tool can assist foundations to consider systematically key factors before engaging in the policy arena and ensure that their mission, values, and level of commitment are consistent with the policy strategies identified.

Conclusion

As stated several times in this article, public policy grantmaking is a relatively recent philanthropic phenomenon. As such, it is still too early to know which grantmaking strategies have been more or less effective. At the same time, experience so far reveals several overarching lessons that foundations should keep in mind when considering their public policy options.

Policy Goals Require Distinct Grantmaking Strategies

Because the policy process is dynamic and the political context surrounding each issue differs, a strategy that works for one policy issue or goal may not work for another. As a result, it is not possible to replicate strategies across policy goals and expect the same results (this approach has been used). While a foundation’s overall positioning in the framework may stay the same, different policy goals will require foundations to support different mixes of activities within that positioning or to emphasize certain activities over others. This article identified a series of steps and issues for foundations to consider when forming their grantmaking strategies. These steps should be considered separately for each policy goal.

Strategies Necessarily Will Evolve

Again, because the policy process is complex and dynamic, foundations must prepare for the likelihood that their grantmaking strategies will change over time. For instance, foundations may need to adapt them in response to shifting political circumstances or opportunities. They also may need to modify them based on what experience or data reveal is or is not working. Foundations must expect and plan for this reality. This includes planning for it on a practical level. For example, program officers should recognize that their public policy grants are likely to require more time and effort than the other types of grants they manage.

Many Strategies Will Require Long-Term and Substantial Resource Commitments

Because foundations often champion causes and issues that receive little attention or support elsewhere, they may find that their issues have little to no pre-existing momentum in the policy arena. As such, grantmaking strategies to advance them through the policy change cycle may require long-term and substantial resource commitments. In such cases, to get real results, foundations cannot “test the waters” or merely dabble in public policy grantmaking. Effective grantmaking strategies will require strong and firm commitments from a foundation’s board, leaders, and staff. This includes the understanding that public policy strategies can take time — often many years — to yield tangible policy results.

APPENDIX 1 Foundation Engagement Tool Part 1: Board Engagement

Questions for Board Papers and Discussions

1. Why consider public policy change?

- What is the program goal, and why is policy change essential to advancing it?

- Why should the foundation attempt to change public policy (consider reasons beyond the opportunity to leverage foundation resources)?

2. What is the policy change goal?

- What, specifically, is the aim (e.g., a new policy, the reform of an existing policy)?

- At what level does the policy change goal need to happen (state government, executive branch, legislative branch, and/or local or regional government)?

3. Why this foundation?

- How central is this issue to the foundation?

- What role will the foundation take (e.g., analysis and planning, mobilizing for action, implementation)?

- How substantial is the alignment between proposed policy goals and actions and the foundation’s core mission, values, programs, and competencies?

- Does the foundation currently have the connections and/or standing to lead or be involved in this effort?

4. What milestones would indicate progress toward the policy goal?

- What is the evaluation approach?

- How will adjustments be made to improve execution along the way?

- What are the priority outcomes and indicators to measure progress toward them?

5. What is the time horizon?

- How long a time commitment is required?

- Is the foundation prepared to commit for the long term?

6. What are the risks?

Risk of failure

- What is the likelihood of success and in what time frame?

- Are the resources available for this effort sufficient to support the selected strategies and achieve the outcome?

Reputational risks

- If the foundation engages on this issue, who will notice, and how will they react?

- What concerns exist about possible reactions of government officials, media, businesses, grantees, or other constituents?

- Is a process in place for dealing with an attack on foundation public policy action from government, media, or others?

Unanticipated consequences

- Have all available and appropriate advisors been consulted to avoid blind spots?

- Will the foundation’s public involvement in this issue make it more difficult to achieve another policy goal?

APPENDIX 2 Foundation Engagement Tool Part 2: Staff Due Diligence and Analysis

Questions to Ensure Solid Strategy Development

1. Where does the issue currently stand in the policy process?

- How fertile is the political and policymaking environment for the change the foundation seeks?

- What are the opposing forces or potential threats in terms of contextual factors, related issues, or specific stakeholder groups?

- How viable is the policy change being advocated (e.g., technical feasibility, compatibility with decision-maker values, reasonableness in cost, appeal to the public)?

2. Who is the target audience, and how must they be engaged to achieve the goal?

- Which audiences can move the issue and achieve the policy change goal (e.g., general public, key influencers, legislators)?

- How far must audiences move (e.g., awareness, willingness to take action, action)?

- What will it take to move audiences forward (e.g., strategies, tactics and resources required, with specific attention to the role of communications)?

- Where does the foundation not need to focus and why (e.g., capacity or actions already in play that can be leveraged, strategy is not relevant)?

3. What is the fiscal strategy?

- Is there a net cost to the reform?

- What is the short and long term strategy for funding the reform?

- Can a return on investment be estimated, and, if so, what would it be?

4. Who else is involved?

- What other funders and groups are working on this and related issues?

- Are there opportunities to work with these other foundations or partners in ways that will increase the foundation’s effectiveness and share any perceived risk?

- Who is in opposition to this public policy goal, and what is the plan to engage or address these individuals or stakeholder groups?

- What is the capacity of partner organizations (including grantees) to be effective advocates? If relevant, how will the foundation build grantee capacity to engage in and sustain this policy work?

5. What are the staff and/or budget implications for this effort?

REFERENCES

Reprinted with permission from The Foundation Review, 1 (3), p. 123 - 131. Grand Rapids, MI: Grand Valley State University.

More information at www.foundationreview.org.